Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the collegial support and guidance of Dr Ro Parsons and Sandra Collins.

Special thanks to the senior leaders of the six schools who generously shared their time speaking with me about their experiences. While it was not possible to conduct in-person case studies with each school due to Covid-19, every school was extremely supportive of the evaluation process.

Evaluation Summary

About the Case Studies

- Case studies of six schools were undertaken to understand and document school experiences with ERO’s Schools: Evaluation for Improvement approach. All schools were at an early phase of the evaluation process and focused their comments on their experience to date.

- Selection of schools was based on principles of diversity in the size of the school, in the type of school, and in location. Two schools were selected from each region.

Strengths of the Evaluation Approach

- All six schools were positive about the philosophy of collaboration and partnership ways of working that underpinned the approach to school evaluation. They believed that a high trust model was the most appropriate way for ERO to work with schools to support evaluation for improvement. From their perspective a strong collaborative base will enable ERO to get a more accurate perspective about what is working and not working across schools in New Zealand.

- School leaders contrasted the previous ERO evaluation approach with the new approach. They valued ERO’s emphasis on providing ongoing evaluation support, rather than relying on a one-off or episodic evaluation of the school. The previous school evaluation approach was seen as narrow, superficial, and judgemental and based on limited understanding of the school context.

- Schools see evaluation as important, and a key responsibility of schools for learning and for accountability. Five of the six schools believed their knowledge and skills in internal evaluation will be strengthened through the new approach. Some of the internal school stakeholders whose views were canvassed in this external evaluation expressed genuine excitement about learning more about evaluation through working with their evaluation partner.

- The evaluation focus and/or evaluation plan in five of the six schools aligned well with the school’s strategic direction, adding value and relevance to the evaluation process, and avoiding duplication of effort. This alignment was seen to enhance the usefulness of the evaluation process and ERO’s work within the school.

- Alignment of the evaluation plan with the school’s existing priorities as captured in their strategic plan or charter avoids duplication of effort and strengthens the relevance of formal evaluation mechanisms.

- Schools appreciated the evaluation partner working alongside them to develop an appropriate evaluation focus for the school. The development of a trusting, collegial relationship with the evaluation partner appeared to be a critical condition in supporting an effective evaluation planning process. The relational capabilities of the evaluation partner were regarded as important as their educational knowledge or evaluation skills.

- Co-design was seen to be a central feature of the approach. While schools were not yet clear about expectations for external reports, they indicated that reports would be developed through a process of co-design, rather than prepared in isolation by ERO.

- School representatives found it difficult to nominate formal improvements to the approach as they were still in the early phases of the evaluation. They indicated that they will better be able to assess the approach after they have progressed through one entire evaluation cycle.

- The strengths of the new approach identified in the survey findings from 66 of the 75 principals involved in Group 1 implementation were reinforced in the deeper-dive case studies.

Concerns about the Approach

- School representatives highlighted the importance of the evaluation partner gaining a good understanding of the school context, and the school’s strategic priorities to shape a useful evaluation plan with the school.

- Internal stakeholders within two schools noted the importance of continuity in the relationship with the evaluation partner to the success of the approach.

- Some of the principals questioned the viability of maintaining collaborative ways of working as the evaluation partner takes on a greater number of schools.

- A small number of school stakeholders noted a concern about continuity of process and understanding of the school context if their evaluation partner were to leave their position.

Sharing Lessons Learnt to inform school improvement

- Representatives of five of the six schools indicated it was important for ERO to share learnings and direct examples about the attributes of good internal evaluation based on their work with schools. Schools are keen to have more guidance from ERO about good practice to support them in improvement. It is clear they understood this to be a feature of the new approach. ERO possesses a wealth of information about what works and what doesn’t work in particular contexts, which could be usefully shared to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of improvement efforts in schools.

Key Questions for consideration by ERO

The synthesis of the case studies reveals five key questions for deliberation by ERO, as presented below.

- How will ERO manage school expectation within existing resource constraints?

- How can evaluative capacity be extended across schools and in classrooms?

- How will ERO align its work with other partners who are also working with schools to progress improvement?

- How will ERO build and maintain its internal capability in evaluation?

- How will ERO support schools with internal evaluation and support external accountability?

- How will ERO know it made a difference at the school and system level?

These questions are elaborated in the synthesis section of this report with recommendations for consideration by ERO.

Each section of this report builds an understanding of school experience and the potential implications of each of the questions for ERO.

Overview of this Report

This report represents the final phase in the external evaluation of the initial implementation of the approach with the initial group of 75 schools. The intended audience for this report is ERO senior leadership team. It is intended that this report will be used formatively to consider opportunities for refinement and improvement of the approach.

Section 1 of this report provides an overview of the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach.

Section 2 presents a description of the case study methodology and the schools that participated in the case study of implementation.

Section 3 describes the current status of the evaluation process in the schools and identified areas of focus.

Section 4 is the major section of this report and provides key messages identified from the cross-case analysis of the participating schools.

Embedded case profiles from each school in the case study are included to add depth and detail to key messages. Reading the profiles in conjunction with the presentation of the cross-case analysis will allow the reader to understand the experience of individual schools during the initial implementation of the approach. Quotes from stakeholders interviewed across the six schools are integrated into each section to evidence key claims.

Section 5 presents a series of key questions for consideration by ERO, their implications and recommendations for consideration by ERO.

Section 1: Introduction

There are over 2500 schools in New Zealand providing education to approximately 850,000 students. Most schools are self-managing state or state-integrated schools, including 112 full Māori-medium kura and 83 mixed Māori language kura.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is the Government’s external education evaluation agency. ERO’s internal and external function encompasses: accountability (including compliance with regulatory requirements), support for improvement and knowledge generation. ERO contributes to the knowledge base about what works in which schools and community contexts to support equity and excellence for all learners. At a system level, ERO conducts research and evaluation to inform priorities and actions for change.

While most schools in New Zealand are providing positive educational experiences for students, inequities remain particularly for Māori and Pacific learners. A central point of inquiry in every school evaluation is the extent to which the school is addressing the needs of Māori and Pacific students, and the impact on equity in terms of learning outcomes.

In response to recommendations in the Review of Tomorrow’s Schools in 2019, ERO shifted its external evaluation approach to a more participatory, collaborative model with increased emphasis on evaluation capacity building and school improvement. Central to the new approach is a focus on ensuring that all schools are on an improvement trajectory.

The structural and operational aspects of the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach were developed in 2020.

1.1 Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach

ERO undertook a research and development process to track alongside the initial implementation of the approach with 75 schools across the country. Fifteen evaluation partners were each allocated 5-6 schools to work through the phases of the evaluation process.

For the evaluation partners the approach was new and reflected a move away from a summative judgement of the school’s performance at the conclusion of a three- or four-day on-site process to an improvement-oriented approach based on collaboration, embedded within the school’s own context that evolve over the course of an improvement cycle.

The Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach in a nutshell

- A shift from event-based external reviews to an evaluation approach that supports continuous improvement

- A shift to a more participatory, collaborative approach to external evaluation built on an understanding of the school context, culture and needs.

- A shift to a more adaptive and responsive evaluation approach.

1.2 The Principles of Practice

ERO developed a set of principles to guide educational evaluation within schools. They are based on improvement-oriented evaluation theory, evidence and practice. The eight principles of practice articulate the characteristics of effective evaluation that should be observed in schools and supported through the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach.

The eight principles are:

- Ko te Tamaiti te Pūtake o te Kaupapa: The child, the heart of the matter - a focus on the learner and equity and excellence in outcomes

- The integration of internal and external evaluation

- A participatory and collaborative process

- A culturally and contextually responsive approach

- Technical rigour in design, data collection, analysis, synthesis and reasoning

- Promotion of evaluation use

- Developing evaluation capacity

- Promoting external accountability and strengthening internal accountability.

A circular diagram labeled "Theory of Action Principles of Evaluation Practice". Two outer rings read "Te Tiriti o Waitangi" and "Capable and Ethical Practice" respectively. Inside the circle is a bolded label reading "Ko te Tamaiti te Pūtake o te Kaupapa". Further points read (clockwise) "Integration of internal and external evaluation", "Technical rigour", "Developing evaluation capacity", "Promoting external accountability & strengthening internal accountability", "Promotion of evaluation use", "Participatory process", "Culturally and contextually responsive approach". In the centre is a green circle with a koru and vine design.

Section 2: External Evaluation of the Initial implementation with Schools

An external evaluation was integrated into ERO’s Research and Development process to support implementation of the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach. The purpose of the evaluation was formative to document experiences to date and identify opportunities for improvement.

The external evaluation consisted of three phases.

- Phase 1: Experiences of Evaluation Partners/Review Officers with initial implementation (completed in January 2021)

- Phase 2: Key internal stakeholder views of the approach (completed in February-March 2021)

- Phase 3: A survey of all principals involved in the initial implementation (75 schools) (completed in June 2021), and

- Phase 3a: Conduct of six case studies of schools involved in the first implementation of the approach (conducted August to December[1] 2021 and completed in February 2022).

Reports were produced from each phase to guide improvement. This third report focuses on presentation of key findings from the case studies of six schools (Phase 3a) involved in the initial implementation.

2.1 The Case Studies

The objectives of the case studies of school experience were to:

- Develop a deeper understanding of how the approach worked in practice in the six schools

- Identify conditions that facilitated or inhibited implementation of the approach in the schools, and

- Identify implications for ERO and opportunities for improvement.

Each region was asked to nominate 4 to 6 schools to inform case selection for this external evaluation. Regions were asked to consider elements of diversity, such as school type (primary, intermediate, contributing, secondary), level of experience of the principal, and school size. Regions were also asked to consider inclusion of schools where partnership approaches appeared to be working well and those where the approach was not working so well.

Two schools were selected from each region using principles of variation as criteria for case selection.

2.2 Case Study Schools

Once selection of the six schools had been made, the external evaluator made contact with the Evaluation Partners/Review Officers assigned to each of the six schools. The external evaluator reiterated the purpose of the case study and asked to share any additional background information that evaluation partners were able to share with the external evaluator (for example, the current draft of the evaluation plan), that may be helpful in supporting understanding of the school context.

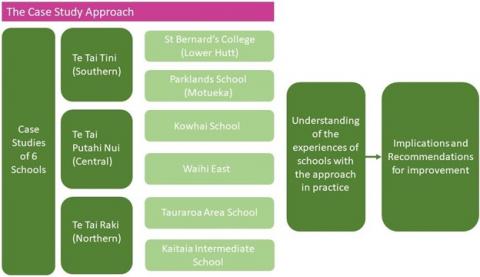

A flow diagram titled "The Case Study Approach"

The first column spans all the rows and reads "Case Studies of 6 Schools".

The second column contains the names of three districts, which each align with two of six school names in the third column. The first reads "Te Tai Tini (Southern)" and corresponds to "St Bernard's College (Lower Hutt)" and "Parklands School (Motueka)". The second reads "Te Tai Putahi Nui (Central)" and corresponds to "Kowhai School" and "Waihi East". The third reads "Te Tai Raki (Northern)" and corresponds to "Tauraroa Area School" and "Kaitaia Intermediate School".

The forth column contains a single cell that reads "Understanding of the experiences of schools with the approach in practice". An arrow points from this cell to the single cell in the fifth column, which reads "Implications and Recommendations for improvement".

2.3 Characteristics of the Case Study Schools

The characteristics of each of the schools in the case study component of the external evaluation are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of Schools

Region: Te Tai Raki (Northern)

School Name: Tauraroa Area School

General Characteristics: Area School, School roll is 500

Students: 26% Māori, including whānau roopu classes

School Name: Kaitaia Intermediate School

General Characteristics: Intermediate School, School roll is 261

Students: Predominantly Māori student population

Region: Te Tai Pūtahi Nui (Central)

School Name: Kowhai School, Hastings

General Characteristics: Special school with a base school and 4 satellites. High proportion of students on Ongoing Resourcing Scheme

Students: 43% Māori students, 11% Pacific heritage, 46% Pakeha

School Name: Waihi East School, Waihi

General Characteristics: Contributing school roll is 200. Early career principal (2 years in role)

Students: 31% Māori students

Region: Te Tai Tini (Southern)

School Name: Parklands School, Motueka

General Characteristics: Primary school Years 1-8, School roll is 206. Early career principal

Students: 40% Māori students, 5% Pacific heritage

School Name: St Bernard’s College, Lower Hutt

General Characteristics: Boys school offering years 7-13 with additional intake at year 9

Students: 26% Māori students, 20% Pacific heritage, 44% Pakeha

2.4 Initiating Contact with Schools

Principals of the six schools were contacted, the purpose of the case studies explained, and a date scheduled for the school visit with the principal. Case studies were originally scheduled face to face, but due to Covid restrictions the two case studies in Northland had to be conducted with key stakeholders via individual or small group interviews on the Zoom platform. Data collection and analysis was undertaken between August and November 2021.

The focus of the case studies was explicitly on schools’ experiences with the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach. Questions of focus were designed to obtain an understanding of

- the school context

- experiences with previous ERO review processes

- principles underpinning the new approach

- experiences of the new approach in practice, and

- suggestions for improvement of the new approach.

The findings presented in this report are based on semi-structured interviews with the principal, and the deputy principal. In three schools’ interviews with a Board of Trustees representative, teachers and small groups of students were also conducted[2].

Each school was asked to provide any additional secondary documentation (for example, findings from consultations with whānau, results of surveys, the school charter) to assist the external evaluator to understand the school context and internal evaluation conducted within the school.

2.5 The Nature of Evidence in the Case Studies

The case studies are illustrative. While the six schools are diverse, their views and experiences of the Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach have a number of common themes about the merit of the new approach. While no claims are made about the generalisability of findings, lessons learned from the experiences shared by these six schools may be transferable across a wider range of schools.

It should be noted that one of the schools represents an outlier case in terms of experience of the approach. They were disappointed with the new approach and expressed reservations about the value of the approach to the school. This school’s experience provides insights into conditions that support or inhibit the success of ERO’s work with schools.

The limitations of the case studies are that there was no scope to triangulate interpretations with the evaluation partners working with these schools. Their perspective would have provided further additional insights and enabled some initial verification of information (for example, school context and key dates).

In the first phase of the external evaluation all ERO’s evaluation partners involved in the initial implementation were asked for feedback about the approach, but the focus was on their experience overall; feedback about their work with individual schools was not sought.

2.6 Analysis and Synthesis

Interviews with school stakeholders were digitally recorded and transcribed. A reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022) was undertaken of each individual school with the school experience of the new approach being the central organising domain.

Data generated from interviews was organised according to interview questions. In this way the external evaluator was able to assess similarities and differences in views or perspectives in each school. A comprehensive case report of each school was then developed. These ranged in length from 10-12 pages.

The cross-case analysis then commenced. Each school was compared and contrasted with other schools in terms of the questions of focus. This cross-case analysis contributed to the development of analytic domains (identified as key messages highlighted in section 4 of this report).

A case profile of one school was also assigned to elaborate the key message and provide richer insights into school experience on the ground. While several schools expressed very similar messages about the value of a collaborative platform and the skills of their evaluation partner, a decision was made about the best fit of each profile to the central messages.

Case profiles were returned to the principal of each school for review. Minor factual errors were corrected (such as length of time a principal had worked at the school), but no substantive changes were made to the case profile.

Approval was also sought for inclusion of photographs taken during the case study visit or retrieved from documentation provided by the school. This final report includes the approved case profiles including some photographs to bring the profiles to life.

Section 3: Overview of Schools: Evaluation for Improvement Approach

The Evaluation for Improvement Approach to school evaluation represents a shift in how ERO’s role and function is operationalised in practice in the school context.

Evaluation Partners/Review Officers and schools work together during the evaluation process. While each part of the evaluation process includes some core tasks, how the process plays out varies in each context. Evaluation tasks may overlap, and there may be a need to return to initial discussions to reinforce key aspects (for example, to re-engage and re-negotiate evaluation parameters).

This more collaborative way of working with schools is designed to foster increased ownership by schools of evaluation processes and to generate evidence for improvement plans and action. Schools are encouraged to use that evidence to inform decisions and activity within the school that will ultimately lead to better outcomes for all students.

Schools may build from one evaluation to another to understand the effectiveness of educational strategies or to generate an evidence base about what is required to improve outcomes for students within their school. Evaluation of the results of improvement actions is a critical part of the school evaluation process.

The new approach means that ERO is not only focused on evaluation capability but also supporting schools with planning and implementation activities. The knowledge and skills of evaluation partners required for this role include,

- knowledge about the conditions and practices or school improvement

- Understanding and commitment to the implications of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

- knowledge of educational theory and practice

- knowledge of evaluation theory and technical requirements for robust evaluation, and

- relational skills in working with diverse school stakeholders.

Evaluation partners are supported by teams and an infrastructure that supports them in their work with schools.

3.1 Case Study Schools – Progress Across Evaluation Phases

All schools involved in the case studies were at relatively early phases of the evaluation process.

The 15 evaluation partners supporting the first group of 75 schools had begun to work with schools between September-November 2020.

By September 2021 four of the six schools had agreed an evaluation focus and a draft evaluation plan had been prepared. The two remaining case study schools were still in discussions with their evaluation partner about the evaluation focus and plan. The research and development process that underpinned the initial implementation with the first group of schools meant that evaluation partners were involved in shaping the practical implications of each phase as they worked with the schools. Evaluation partners were also involved in professional learning and team-based discussions with colleagues in their region and across the country, most of which occurred over Zoom.

It appears that evaluation partners spent a lot of initial time with schools communicating the rationale and philosophy of the new way of working with schools. They worked hard to build a collaborative foundation. The time taken in the initial set up of the evaluation process may also reflect some uncertainty by the evaluation partners of specific evaluation requirements or tasks, due to the developmental nature of the process.

While it was anticipated that implementation of the phases would progress more quickly, discussions and meetings were hindered by Covid-19 uncertainty and school lockdowns.

A summary of each school’s agreed evaluation focus is presented in Table 2 on the following page. The evaluation focus statement and key evaluation questions were taken directly from draft evaluation plans or working documents.

Table 2: Current Status of School Evaluation – October 2021

School: Tauraroa Area School

Status: Designing completed. Draft Evaluation Plan

Evaluation Focus:

Strengthening teacher’s assessment data literacy and rationalising assessment to provide reliable and timely assessment information

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

- How effective is our assessment in supporting teaching and learning that contributes to engagement, equity, and excellence for all learners?

- How effective are we in responding to evaluation and assessment for improving outcomes for all students?

School: Kaitaia Intermediate School

Status: Exploring and focusing

Evaluation Focus:

How effectively are school processes and teaching practice raising student achievement and building a learning focused culture that holistically promotes the wellbeing, language, culture, and identity of all students?

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

Not applicable

School: Kowhai School

Status: Designing

Evaluation Focus:

To strengthen internal evaluation and the school’s ability to improve

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

Evaluate the effectiveness of Kowhai TEC transition processes and practices and how they are supporting students to successfully transition from school to community (including a number of evaluation questions).

School: Waihi East School

Status: Designing

Evaluation Focus:

How effective are the use of the school’s values in the curriculum, supporting equity and excellence, wellbeing, and improved student outcomes?

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

- To what extent are the school values visible in student learning?

- In what ways do the school values support students in their learning at school and at home?

- How well do the values support the graduate profile outcomes?

- How does the deliberate teaching of school value impact on wellbeing?

School: St Bernard’s College

Status: Exploring and focusing

Evaluation Focus:

Equity and excellence for Māori and all other priority learners: How do we know?

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

- Developing an evaluative practice model to support effective relationships for learning between teachers and students.

- Building evaluative practice to strengthen effective relationships for learning between teachers and students.

- Impact of ongoing evaluation practice that supports effective relationships for learning between teachers and students.

School: Parklands School

Status: Designing

Evaluation Focus:

Responsive curriculum and opportunity to learn: Reading in years 4 to 6.

Evaluation Questions (as framed in the evaluation plan):

The purpose of the evaluation is to explore the effectiveness of reading practices in years 4-6 (including effective teaching and assessment practices for reading, which promote student engagement, high expectations and continuity of learning.

Section 4: Findings

4.1 Views and Experiences of the Approach

As all schools were still at early phases in planning and designing the evaluation, they were not in a position to assess the approach as a whole at the time data for the case studies was collected. To date, the experiences in five of the six schools has been positive[3].

Principals and senior leaders welcomed the philosophy of participation and collaboration that underpinned the new approach. While ERO had communicated the elements of the approach publicly, some principals and teachers remained wary about how it would work in practice. Schools are frequently exposed to new models, frameworks, and approaches from a range of sources, and for some school stakeholders these frameworks do not support meaningful change; they are perceived as ‘window dressing’ and there is an expectation that nothing may change in practice.

At the beginning of most evaluations, stakeholders may feel uneasy because they do not have full oversight of the evaluation process, or may be anxious about the potential burden of the evaluation. Historically, ERO evaluation processes were associated with external judgement of the school. In the new approach the school and the evaluation partner make decisions together about the areas of focus of improvement efforts, given an understanding of the school context and strategic plan, the purpose and scope of the evaluation, the roles and responsibilities of each party and how evidence will be used for planning and evaluation of improvement actions.

Once the schools met with their evaluation partner some initial questions or concerns about the new approach were addressed. Through discussion the school developed an understanding of the practical implications of the approach. School representatives considered that the evaluation partners described the philosophy behind the new approach clearly.

When asked what terms they associated with the approach school representatives used terms such as, ‘collaborative’, ‘co-design’ and ‘partnership for improvement’ to describe the key features of the new approach. Most interviewees anticipated that the partnership established with the evaluation partner will ensure that the evaluation process remains collaborative throughout the evaluation cycle, from design, data collection, analysis, synthesis through to reporting.

4.2 The Value of a Collaborative Platform for School Evaluation

While it has become common in the educational evaluation literature to recommend collaborative approaches, the theory needs to translate into practice. This requires a number of questions to be addressed:

- What does collaboration mean in the context of ERO working with schools to support evaluation for improvement?

- Who provides the leadership for collaboration? How are collaborative processes maintained?

- What are the limits of collaborative practices for co-design and partnership throughout the evaluation process, including reporting?

Schools were unanimous in their support for ERO’s move to a more collaborative approach to school evaluation. Collaborative ways of working were seen to have more integrity; the school works with ERO over time on evaluation processes that will inform improvement.

One of the principals referred to the shift they had already observed in the evaluation process:

“This (new approach) does not seem like a tick box thing. The school is not being scored at a particular level. It’s not judgement focused or performance management. It’s working together for improvement through open channels of communication and trust. We don’t feel like we need to put on a show for our reviewer.”

While schools were not sure about the parameters of the approach in its entirety (particularly data collection and reporting requirements) or the implications for the school, they were confident that the collaborative platform established with the evaluation partner will allow understandings of the scope of the approach to unfold over time. As one principal put it,

“I would imagine that if we are working from a truly collaborative basis that there will be no surprises. We will be working it out together as we go along.”

Schools indicated that the prior review model often felt rushed. It was a snapshot judgement of the school by an external agency with a limited knowledge of the school context. Interviewees indicated that the new approach will be of value to the school, and more value to ERO because of the collaborative base. One principal explained the differences that a collaborative foundation makes to the potential for greater transparency and learning:

“I think it’s far more of an open relationship and allows a greater look into the depths of how the school’s working, what we’re working on, how we’re changing things, where the gaps are, how we’re planning to address them. Before it was this tiny snapshot that they would have during the week or so that they would come in, and the whole school felt the stress and pressure. That is nothing to do with the reviewers that came in, they were always very nice, but it was just that stigma that was always attached to ERO: ‘They’re here, be on your best behaviour, make sure you’ve got everything up to date,’ and you’d see people crossing the Ts and dotting the Is. Whereas this new model is far more relaxed, people feel comfortable to have conversations and to talk about actually what’s genuinely going well, as opposed to, “What can we think of that they’re going to want to hear, that we could show evidence of?”

The following case profile illustrates the value of the collaborative platform to school evaluation in increasing the utility and transparency of evaluation within the school. The case profile begins with a description of the school context and important areas of focus for the school, and then describes their experience of the benefits of EROs collaborative approach to evaluation to date.

Comments on the evaluation process were based on reflections to the initial meetings with the evaluation partner and discussion of the approach, the development of evaluation focus and the drafting of the evaluation plan.

Case Profile: Waihi East School - A collaborative platform for evaluation

School Context

Waihi East School was established in 1907. Waihi East is a co-educational contributing school catering for children in the 5 to 11 year age range (Years 1- 6). At the end of Year six transfer to Waihi College (Years 7-13). The school roll is approximately 200 students and 32% of the students identify as Māori. Prior to the implementation of the new approach to school evaluation by ERO, the school had not experienced an ERO review for seven years.

A number of the students attending Waihi East School experience disadvantage. During Covid-19 lockdowns, the challenges some of the students’ families faced were exacerbated. These experiences influence the level of students’ engagement in learning.

The wellbeing of students and of staff is a key focus for the school. Partnerships within the school, and between the school and whānau, and the wider community are emphasised in planning and in decision making. The focus of the school team on wellbeing is also based on the view that unless students are settled and safe, they will not be prepared for learning.

The school focus on ‘holistic wellbeing’ of students reflects the view that it is important to emphasise what 'grows and glows’ students. While the leadership team focus on progress in academic outcomes, they regard life skills as equally important.

Te reo Māori is a part of classroom culture and Māori tikanga (customs) are integrated into curriculum areas. The school offers a range of tikanga activities such as kapa haka, and mihi whakatau, marae visits, te reo kori, waiata tawhito (local songs) and tikanga time. The whānau roopu created a waiata for the school and the song is performed at school gatherings. Regular whānau roopu huis are held at the school.

The five working documents that support Māori and Pasifika success within the school are, Ka Hikitia, Tataiako, Tau Mai Te Reo, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) and the Pasifika education plan.

Waihi East School has three strategic aims:

- Tiriti o Waitangi – working to ensure that plans, policies and local curriculum reflect the partnership, participation and protection obligations we strive to achieve for all.

- Partnerships – working to ensure that plans, policies and local curriculum reflect local tikanga and Te Ao Māori.

- Raising Student Achievement – accelerate learning for priority and at-risk students, improve teacher pedagogy and improve student outcomes.

The principal has been in her role for the past two years. However, while a relatively new principal, they are an experienced teacher and local resident, having lived for over 15 years in the area. They have taught at Waihi East School and other schools over that period of time. The principal has taken on a range of leadership roles including a role within the Kāhui Ako alongside the deputy principal.

A number of staff interviewed during the collection of data for this case study spoke very positively about the school culture and the ethic of care that extends to all areas of the school.

Working with ERO - A collaborative foundation

ERO’s commitment to collaborative ways of working with schools on evaluation was welcomed by the principal and deputy principal. They support a tailored approach to evaluation that reflects the school context and is able to document the ‘school’s story’. For Waihi East a one size fits all evaluation approach with schools will not allow an accurate or comprehensive representation of the unique challenges and opportunities schools may experience.

Understanding the context of each school is a critical element in educational evaluation, and school representatives from Waihi East felt that their evaluation partner was developing a solid understanding of their school community.

The opportunity to collaborate with the evaluation partner in developing and implementing evaluation within the school was identified as a strength. Senior leaders believe that this approach will grow capability within the school and build on priorities for student wellbeing and achievement. The principal commented,

“We are all here to support students to reach their potential…If you collaborate then schools are going to improve because the school can be more open and it’s based on a relationship. It means there is trust on both sides.”

ERO’s prior approach to school evaluation

Waihi East teaching staff interviewed for this case study contrasted their experience of the new approach with previous review processes. While the new approach is explicitly collegial and interactive, the prior approach felt judgemental and superficial. Teachers indicated that while the reviewers seemed respectful and friendly, ERO’s focus on judgement of school performance outweighed the interpersonal and relational attributes of the reviewers.

Teachers felt like they were ‘under the microscope’ and felt pressure to demonstrate their competence. One of the teachers in the school suggested that the previous approach communicated a level of professional disrespect for the teaching role.

“For me understanding pedagogy and practice is not about flicking through a teacher’s plan. It’s way more than that. We are professionals, but we always felt like we were being personally assessed.”

The synthesis process and public reports missed capturing the unique characteristics and features of the school. A teacher with experience of multiple ERO reviews suggested that the outcome of the review (the report) did not comprehensively reflect the school’s story or what had been shared with reviewers:

“Two to three days’ work and this would all be translated into a three-page report. We would produce all this information and include butcher’s paper across the whole wall of the library, and this was shortened into a summary that for us didn’t reflect the conversation. The essence of the school was not there.”

The potential of the new approach

For this school collaborative ways of working foster trust; the relationship is primary in building trust. The evaluation partner and the school work together on evaluation and improvement. Reports are produced through a negotiated process that is grounded in the collection and analysis of a range of evidence over time.

Working alongside the school means that the school’s accountability for improvement is not limited to the end; it is integral throughout the entire evaluation process.

“Having the evaluation partner work alongside the school is really valuable. There is a much greater opportunity for an external pair of eyes to see things that we may not have seen. It is way less stressful and more real. I get the sense that it is not about comparing one school against another school on some narrowly defined set of criteria, but really focusing on getting an understanding of the school, its context and students.”

The new approach has the potential to create reports that are more relevant and readable, and that may be useful resources for the school and for the wider community. The principal understands that public reports provide the community with information that may be important for families in selecting schools for their children. However, in her view public reports need to reflect the character of the school, as well as its performance.

Waihi East School leaders identified several benefits of the new approach, both for their school and for ERO. They believed that the new approach would provide ERO with an evidence base about what works and in which contexts across regions and schools. Sharing this information with schools will facilitate school improvement efforts as actions can be made that have worked in similar and different school contexts.

“ERO will get a much more accurate picture and a better understanding of different schools and what is working and not working, which would be a great resource for us if it was more widely shared.”

4.3 Strengthening evaluation capability

Internal stakeholders in five of the six schools believed that working with the evaluation partner over a period of time will improve their skills in internal evaluation. In their view, evaluation provides the evidence base to drive planning and delivery of change. It is not supporting evaluation capability for the sake of doing evaluation.

The evaluation partner from ERO is external to the school, and in this role is able to ask critical questions and facilitate discussion about areas for improvement. They are able to ask the ‘sticky’ questions and focus in on the most critical mechanisms that will foster school improvement. Their knowledge of school conditions and curriculum that support improvement, and their evaluation skills are a resource to the school. The unrelenting focus on equity and excellence and school improvement in line with these outcomes supports schools to “keep on track” with their improvement agenda.

Schools are accountable to students, their families, the school Boards, and to the wider community and saw the process of working with ERO as an opportunity to strengthen both internal and external accountability.

School leaders indicated that the skills they will learn through working with their evaluation partner will be sustainable, and applicable for subsequent evaluations. Schools have the opportunity to draw on a knowledgeable evaluation partner to develop questions, identify data collection mechanisms and produce useful insights. The tools that the evaluation partner shares with the school will become ongoing resources for other evaluations, this lessening the need for ongoing capability building.

A member of the senior leadership team at Kowhai School highlighted the opportunities for learning for the school that will benefit the school over time.

“We hope we will be able to evaluate in the future once we have developed the knowledge and skills about how that will look from this process. In the past, the model has been just to write down and record what you do. It was not a model that was about learning how to evaluate or how to improve.”

It is clear that schools will have different levels of existing evaluation capability and capacity, and evaluation partners will need criteria to assess the level of support required. Schools saw this as a strength of the new approach as the way the evaluation partner works with the school can be tailored to their needs.

The capacity to tailor the process to school need raises two questions for consideration:

- How will assessments of existing school capability and capacity in evaluation be made?

- Is the evaluation partner able to provide the level of support expected by schools, given practical constraints on resourcing and existing skill sets?

The following case profile from Parklands School provides some insight into the role the evaluation partner plays in building evaluation capability.

Case Profile: Parklands School: Strengthening Evaluation Capability

Parklands School is a primary school for students in Years 1 to 8 located in Motueka. Forty percent of the students identify as Māori, and there are an increasing number of students from diverse cultural backgrounds enrolling in the school. The student population is 186 students with a large number of these students (up to 73) on a needs register, who require additional support with their learning.

Pou whenua at Parklands School, bearing the school’s identity and values

The school is situated on a site with an attached technology centre catering for Years 7 to 8 students across the district. A family service centre, playcentre, early childhood centre and community oral health clinic are also located on the school site. A school social worker, strengthening families coordinator, a resource teacher of Māori and a highly respected kaumātua kuia (Māori elder) are also based at the school.

A member of the staff team created the carvings that stand at the school entrance and these pou whenua host the school values of KAHA: Kotahitanga (working together); Ako (learning); Haepapa (responsibility) and Aroha (empathy). At their completion a blessing was held, which was attended by over 100 people, including local Iwi, parents and whānau.

The school has strong Iwi involvement - both manawhenua – Te Atiawa and Ngāti Rarua and connection to Te Awhina (the local marae). Representatives from local Iwi participate in strategic school meetings.

The current principal began in her role in 2020, but is not new to the school or to the community. They have an extensive history with the school, having begun as a teacher at Parklands in 1997. As principal, they are eager for the school to become a strong cultural hub within the community.

The school is focused on preparing students to achieve in Māori and in English. Parklands has a Māori bilingual unit made up of 3 bilingual classes. The school offers Immersion level 2 (60% of curriculum taught in te reo Māori for more than 12.5 hours a week). The school aims to build up all classrooms in te reo Māori immersion level 4 (12% to 30% of curriculum taught in te reo Māori for more than three hours a week) across the school. The vision of Parklands is that students leave the school with:

- pride in themselves, their culture, their school, and community

- a strong sense of who they are and their potential

- the knowledge, skills, and mindset to engage in further education, and

- confidence in their ability to learn, change, adapt, and grow.

Working with ERO on evaluation

The principal believed that work with the evaluation partner was contributing to improved school capability in evaluation. They recognised that as a principal they needed to engage in monitoring and evaluation, but initially did not know where to begin with the process. They were enthusiastic about working with the evaluation partner and getting additional support for internal evaluation.

“When the new model started up and I heard that it would help the school build its evaluation knowledge and skills I thought, ‘yes.’ Before then I didn’t know where to start. As a new principal there were all these folders with evaluation information in them... I knew I would be able to do evaluation, but the guidance from [our evaluation partner] has been invaluable.”

The principal explained ERO’s new approach to the staff team after the initial meeting with the evaluation partner. They felt that some teachers were initially sceptical that the new approach would be different from the prior approach. These teachers had experienced a number of prior reviews that appeared to be ‘narrow and focused only on what ERO wanted to know, not the full school context.’

Building and Sustaining School Capability in Evaluation

The school and the evaluation partner worked together to develop the plan in their second meeting. The evaluation planning discussion began with reference to the school’s strategic plan and the goals of the school.

Literacy had been identified as the key focal area of improvement in the strategic plan. The principal engaged with the reading recovery specialist in the school to contribute her ideas and insights to the evaluation plan. The purpose of the evaluation is to explore the effectiveness of reading practices in years 4-6 (including effective teaching and assessment practices for reading, which promote student engagement, high expectations and continuity of learning). For the principal there was strong alignment between the strategic directions of the school and the evaluation focus, which adds value to the school.

Students at Parklands School

ERO’s work with the school presents an opportunity to maintain the school’s momentum on improvement and sustains their focus on what they are trying to achieve. The principal commented on the utility of the evaluation to the school.

Literacy had been identified as the key focal area of improvement in the strategic plan. The principal engaged with the reading recovery specialist in the school to contribute her ideas and insights to the evaluation plan. The purpose of the evaluation is to explore the effectiveness of reading practices in years 4-6 (including effective teaching and assessment practices for reading, which promote student engagement, high expectations and continuity of learning). For the principal there was strong alignment between the strategic directions of the school and the evaluation focus, which adds value to the school.

ERO’s work with the school presents an opportunity to maintain the school’s momentum on improvement and sustains their focus on what they are trying to achieve. The principal commented on the utility of the evaluation to the school.

“I like working smart. And this isn’t something else on top or doubling up on what we are already doing. The conversations started with our strategic plan. It is an action plan that reflects our strategic plan and strategic directions. Our strategic plan is about things that will make our school better. We worked backwards to identify gaps and evidence, and then develop an action plan. The evaluation plan is doing work for me. I can show our Board this.”

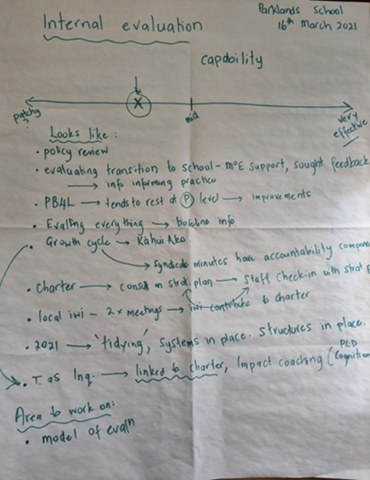

The principal explained the way the evaluation partner facilitated development of the evaluation plan through discussion and note taking on butcher’s paper. The principal keeps the butcher’s paper on the back of her office door as a reminder of agreements and areas of focus.

The school believes the final evaluation plan is ‘their’ plan, not ERO’s plan. The plan will provide guidance to the school for other evaluative work. The process of developing the plan also enables the school to build its capability in evaluation, which can be extended to other domains of inquiry and improvement.

It is likely that subsequent planning phases may be streamlined as the school will have the knowledge and skills needed to progress their own plans for improvement. The principal stated,

“The evaluation plan was built together. We sat here and we brainstormed some ideas, and the evaluation partner wrote it down… Part of our thinking is now that we have this evaluation plan, we can replicate it in other areas. We can apply the learning to other year levels, and also use the evaluation plan to plan other evaluations.”

After the evaluation plan was drafted, the principal shared it with other members of the senior leadership team in an open forum. The principal asked teachers from years 4-6 for their reflections and feedback on the plan, and to consider the implications of the plan for them.

Student voice and perspectives will also contribute to understanding experiences students have with reading in years 4-6 and the evaluation partner is going to assist with capturing student voices over an upcoming two-day visit. Māori whānau perspectives and voice will be gathered as part of the evaluation through consultation and a survey.

Parklands School evaluation plan discussions noted on butcher’s paper and used as a reminder of agreements and areas of focus.

The evaluation partner as a Change Leader

The principal shared her view that the evaluation partner supports the school to ask critical questions. While the previous approach appeared to be focused on accountability without an appreciation of context, the new approach is intended to be about learning for improvement.

The school recognises the value of strong internal evaluation as a ‘matter of good practice.’ EROs approach builds opportunities for more open exchange about what is working or not working within the school, and practical ways of generating evidence to inform improvement. It is envisaged that evaluation findings may also be used to advocate for additional resourcing and support for school and student needs.

In the principal’s view the perceived shift from regulation and inspection to collaboration and co-design with ERO is significant. It is indicative of a shift in mindset about what will contribute most in supporting improvement in schools.

“ERO is now interested in the school context and looking at our data and hearing our story. There seems to be more flexibility built into the approach. They (ERO) are not coming in to ‘check’ on us in the same way as before (the previous review approach). The conversations we have with our evaluation partner are great. They are not always easy conversations, and they challenge us and ask us to think more critically about what we are doing. Working with ERO now is like having a change leader in evaluation work”.

4.4 Construction of the Evaluation Plan

ERO’s evaluation approach provides an opportunity to develop an evaluation plan that is tailored to the school and builds internal capability in evaluation. The plan is not only for evaluation, but for evaluation and generation of evidence that will support planning and improvement actions. Schools understood that the evaluation plan, and the actions that stem from the plan and from evaluation, will lead to school improvement. Qualitative and quantitative data is powerful and the potential to collect rich sources of evidence throughout the evaluation was seen to be a strength.

The focus on the relevance of the plan to the school is a stark contrast to the previous review approach. For school stakeholders the previous approach had focused on what the school had done and school performance, rather than strengthening evaluation knowledge and skills that are grounded in an appreciation of school and community context.

While schools recognised that ERO still has to verify what the school has done in terms of public accountability, they believed that the final report will have elements of co-construction. It was clear at the time the case studies were conducted that school stakeholders were largely unaware of the formal requirements for reporting or the required process for generating them. At that stage, reporting requirements were still under development.

The case profile below illustrates the experience of the evaluation planning process within Kowhai School. The case highlights the ownership the school has over the evaluation plan, and the difference school leaders believe this will make to their improvement efforts.

Case profile: Kowhai School: ‘It’s our school evaluation plan’

Kowhai School was established in 1975 and has a focus on providing integrated educational experiences for all students. The network of base and satellite classes offer pathways through lower primary, upper primary, intermediate, and high school.

Students are able to attend Kōwhai School from age 5 until age 21. Currently, the school roll is approximately 100 students, with growing demand from the community for places in the school.

Determining the evaluation focus – School transitions

The evaluation focus for the school was co-constructed with the evaluation partner, the deputy principal and another two members of the school leadership team[4]. In the initial meeting with the evaluation partner the group discussed potential areas requiring further development.

They were aware that settling on the evaluation focus requires consideration of a range of issues, including clarity about the purpose and intended use of the findings.

Support for effective transitions had been identified as a key direction for the school for some time and was selected as the evaluation focus. Issues of scope were also discussed in the evaluation planning session. While there had already been a lot of work to support students’ transitions, the school recognised it needed to do more work to support students in their educational pathway and post-school services and employment in the community.

The alignment of the evaluation plan with the school’s strategic directions has made the evaluation process ‘incredibly useful’ to the school. For the principal and the leadership team the process of chunking the evaluation into stages or phases helped build confidence in their capability to complete the evaluation. While separating the evaluation into phases made the process more manageable, it was the evaluation partner’s knowledge of the school and community context together with her evaluation knowledge and relational skills that reinforced their confidence in the evaluation process. The principal explained:

“We are directing the evaluation, but with [the evaluation partner’s] support and guidance. They are really good at putting us at ease and validating what is important for us as well. They understand] the school context, and they know the evaluation work. They ask us critical and often challenging questions, but in a way that is not threatening to us.”

As a follow up action, the school hosted an evaluation forum to progress work on their evaluation plan. The school used the forum as an opportunity to seek feedback from students, parents, whānau and agencies about their transition experiences. They invited school leavers from 2018, current students and families as well as some agency representatives.

The forum was well attended, which the school attributed in part to a personalised invitation and follow up phone call.

School staff posed four or five key questions to the group during the forum. Post-it notes and butcher’s paper were used to capture the feedback from participants, parents, whānau and transition agency representatives who attended the forum. The school collated feedback, including photos from the event. The school plans to share the report with their evaluation partner on her next visit.

A group of students at the feedback forum – Kowhai School

From the school’s perspective collecting data over time will allow them to review aspects of their practice on an ongoing basis, to keep the focus on how the school can improve transition experiences better for students and their families.

The deputy principal commented on the usefulness of the feedback and its use for school planning and improvements:

“We wrote it. We built it together. We sat here and the evaluation partner took notes and then went away and typed it up. It captured what we had discussed. It wasn’t her plan, or ERO’s plan. It is our plan, our school’s plan.”

4.5 The Need for Differentiated Evaluation Support

ERO’s evaluation approach is based on tailoring evaluation support to schools based on their needs. There may be value in ERO exploring criteria for providing differentiated support schools for evaluation, providing more intense support for some schools and more of an oversight evaluation role in others. Differentiation will need to be based on a diagnostic discussion with the school and with any agency partners involved in providing support to the school. In schools where evaluation capability and capacity are already strong, ERO’s role could offer a ‘lighter touch’ to monitor progress and outcomes.

There are also school contexts when the ongoing involvement of the evaluation partner may not be warranted because the school already has external groups or agencies working with them on strategies for school improvement. In these contexts, the evaluation partner will need to carefully tailor the level of support to avoid duplication and confusion.

The following quote from a Student Achievement Function (SAF) practitioner highlights a potential concern when multiple agencies are working with schools. If the school has a high level of maturity, capability and strong direction and capacity to deliver on this then we merely confirm this and get out of their way.

“There needs to be more clarity around which plan … is driving improvement. I work with the school on a regular basis to develop and implement a change plan and that change plan might change depending on how it goes in supporting improvement. It is an inquiry-based model with evaluation built into it. But there is a risk that these plans become another layer of administrivia being put in place…It would be better if the evaluation plan lined up with what the school is already doing, rather than adding another layer of complication. We are both supporting the school… It’s a system and process issue, not a criticism of any agency or tools and templates.”

The school profiled below is Kaitaia Intermediate School. The school is involved in a range of change initiatives designed to support teachers and student wellbeing and school performance.

The case profile presented below highlights the importance of tailoring the evaluation process to the school needs and considering the appropriate scope of engagement.

Case Profile: Kaitaia Intermediate School, a case for differentiated evaluation support

School Context

Kaitaia is a community of over 6000 people who live in both urban and rural areas. The main industries in the area are forestry, tourism, and farming. Unemployment is higher than the regional average. Kaitaia Intermediate School is a contributing co-educational state school for year 7 and 8 students, currently serving 240 students.

There are nine classroom teachers, four technology specialist teachers, one Rāranga weaving teacher, and a Resource Teacher Māori who work alongside administration and support staff.

The school hosts three bilingual classes to provide te reo me ōna tikanga programmes for those who choose high level 4 to beginning level 2 bilingual immersion at years 7 and 8. A level 3-4 te reo programme in mainstream classes is also provided to encourage students and staff to become more confident in identity, language and tikanga practices.[5]

The acting principal and deputy principal pointed to the unique opportunities and challenges of intermediate schools, which only have students for two years of their education, which means that at the start of every school year half the students are new entrants to the school. Students join the school from one of eight feeder schools and in the first several months they must learn to adapt to a different school environment. The school focuses on supporting students to learn how to get on with others, adjust to a more complex school structure, and develop aspirations for the future.

The school has a two-fold vision that exemplifies the focus on the academic, social, cultural and personal outcomes of all students. The first vision is that students will be ‘confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners who demonstrate respect, responsibility and form positive relationships.’

Kaitaia Intermediate School values

The second vision is that the school will develop ‘the academic, social, emotional and physical wellbeing of all students through a focus on Ako, Manaakitanga, Whānaungatanga and Moemoea.’

A context of disadvantage

School data indicates that the school faces ongoing challenges with low achievement of students particularly in maths and literacy. Achievement disparities are more prevalent for Māori and male students.

The challenges that students face have been exacerbated over the past two years as a result of Covid-19. Attendance is a key issue for the school.

Sustainability of a partnership approach

The acting principal and deputy principal acknowledged the importance of ERO’s role in supporting the school’s evaluation. They appreciated the shift to a collaborative approach where the evaluation partner works alongside the school.

The previous approach was episodic and focused on assessment with little apparent appreciation of the school context. The principal explained the implications of the shift towards a more collaborative approach by contrasting the new approach with the previous approach to school evaluation:

“In the past ERO would come in, and they would observe and make judgements based on what they saw and it came down to a judgement of academic achievement. We understand that achievement is important, and that is why we are here. The context is that our students may be entering school at a level that is lower than anticipated. The chance of us getting students up to the expected level of secondary school is a challenge. A focus on academic achievement does not take into account our context and the challenges facing students and families here. The new approach does take that into account. We are growing students in a range of ways – in reading, writing, maths and we are also focusing on them having aspirations, goals, routines, and being good citizens. We are shifting our emphasis from just achievement to demonstrating progress.”

While the principal and assistant principal valued the collaborative approach, they felt that there had been insufficient level of engagement to date to progress the evaluation plan. The school expressed a preference for more regular contact with the evaluation partner. This was not a criticism of the evaluation partner; the school was aware that the evaluation partner was working across multiple schools, and they also acknowledged the impact of Covid-19 lockdowns, which had prevented in-person evaluation visits. Both senior leaders expressed concern about the integrity of a partnership approach if the evaluation partner was not sufficiently resourced to work in an ongoing and regular way with the school.

Agency engagement with the school

The school is currently being supported by a skilled practitioner serving in the Student Achievement Function (‘The SAF’) and working alongside an experienced educational consultant. The educational consultant is supporting the school with student learning profiles and the broader mission statement for the school. The SAF practitioner is working with the school on a change management process to address staff and student wellbeing within the school. The evaluation partner from ERO is working with the school, the SAF practitioner and the educational consultant in development of the evaluation plan.

The school adopts an inclusive whole school approach to planning, involving all staff, including the caretaker and administration staff in professional learning and development. This communicates an important message that everyone is a leader and has responsibility in being visible in supporting students within the school.

EROs evaluation planning process engages with the agencies that support the school. However, there appears to be a potential risk of duplication of effort as the SAF practitioner and the educational consultant have in-built inquiry learning and evaluation mechanisms to monitor progress against plans. The creation of a separate evaluation plan may potentially duplicate what other agencies are doing in the school and contribute to confusion about purpose and role.

The SAF practitioner emphasised the importance of clear roles and responsibilities of agencies working with schools to avoid confusion.

“If a school is tracking well, they may really value ERO’s role in supporting them to evaluate. If there are others working around improvement where monitoring is already built in, then it might be better for ERO to step back and allow them to do what they do. Otherwise, clarity gets lost. ERO can then come back into the school and evaluate the outcomes of that work.”

Kaitaia Intermediate School Library

In school contexts where multiple agencies are present and working with the school on improvement, it may be more useful for ERO to maintain an oversight role and plan for a strategic level evaluation of the effectiveness of the change efforts within the school. There is potential for the evaluation partner to establish overarching evaluation mechanisms to monitor the impact of work designed to improve learner achievement, and to evaluate the contribution of partnership ways of working among agencies and schools in progressing improvements.

The approach to school improvement and to evaluation is a team approach. The school works with ERO, the Ministry, and other providers to determine the necessary resources to make improvements. The challenge in inter-agency working is to clarify role expectations among all stakeholders to ensure the process is of value to the school and does not add layers of confusion or redundant paperwork. ERO’s evaluation can then be used by the school and by agencies to understand the benefits of joined-up approaches to school improvement

4.6 The Role of the Evaluation Partner

The preceding discussion has highlighted that schools value the collaborative foundation that underpins the new approach to school evaluation. This points to the need to consider the attributes and skills that evaluation partners bring to schools to support an improvement-oriented approach to evaluation.

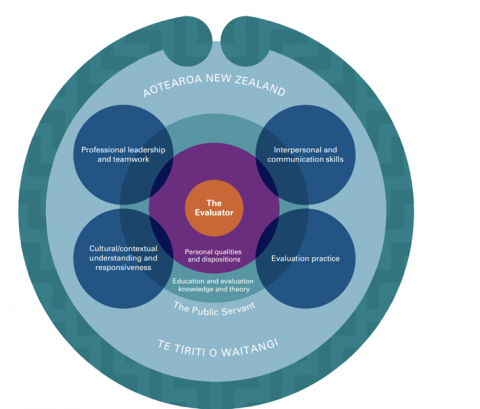

ERO has identified the knowledge, expertise and personal qualities and dispositions required for high quality education evaluation through the evaluation capabilities framework.

The evaluation capabilities are intended to ensure professionalism, guide professional learning within the organisation, shape quality assurance mechanisms, and strengthen the credibility and integrity of ERO’s evaluation work.

The core capabilities reflect the requirements of an education evaluation role within Aotearoa New Zealand, that is cultural and contextual understanding and responsiveness, professional leadership and teamwork, evaluation knowledge and practice, and interpersonal and communication skills. The relationship of these capabilities within the context of evaluation for improvement in schools is depicted in the diagram below.

Evaluation Capabilities

Evaluation is a profession with a specific set of professional skills and competencies. Becoming knowledgeable and skilled in evaluation takes time. The role requires a range of technical, practical, and relational skills. Evaluation partners need to possess:

- knowledge of conditions that need to be in place for school improvement

- understanding of the New Zealand education system and the policies and frameworks used to support school improvement

- understanding and commitment to the implications of Te Tiriti o Waitangi for equity and excellence

- ability to establish and maintain professional relationships

- capacity to adapt and flexibility in problem solving

- capacity to convey evaluation concepts in a concise and clear way that is appropriate to the audience

- good writing skills to translate discussions into actionable plans

- knowledge of major approaches to evaluation and data collection, and

- strong ethical standards and commitments.

The required skill set is extensive and requires knowledge and skills across a range of domains – education, evaluation, and organisational development.

Experienced evaluators are able to skilfully adapt their skills to fit the needs of schools and school stakeholders. For newer evaluators, the knowledge and skills will develop over time with experience and from learning about the most effective ways to work with schools.

While evaluation partners bring different strengths to their roles and the process is tailored to schools, there is a need for consistency in practice. Templates and tools provide some guidance on process requirements and support ongoing monitoring, but need to be supplemented with opportunities for feedback, continuous learning, and critical reflection.

Evaluation partners are part of an evaluation team, with supervision, and have access to professional learning opportunities to strengthen their knowledge and skills. ERO had a range of resources available to evaluation partners and access to a range of tools, national research, and evaluation outcomes. ERO will need to identify ways to provide ongoing support and capability building according to the scope of practice as it evolves over time.

4.6 1 Experience of Working with the Evaluation Partner

The evaluation approach emphasises the development and maintenance of a collaborative partnership between the ERO evaluation partner and the school. For five of the six schools their experience of the evaluation partners had been very positive.

In most schools the evaluation partner was already known to the school having worked with them in prior reviews or, in one case having conducted research with the school via Zoom in 2020 on the impact of Covid-19 on schools. The basis for the collaborative relationship had already been established. In this context, the schools did not notice a shift in the way the evaluation partner worked with them. In their view, the evaluation partner had always been respectful, considerate, professional and collegial. However, the philosophy underpinning the new approach gave this relational way of working more legitimacy and enabled the evaluation process to be more explicitly collaborative. A school principal from one of the schools commented:

“In the past I often got a feeling that some of the people were constrained. They were nice enough, professional, but they were sort of hampered by this set of expectations. Now, there is a recognition and a focus on context, and on relationship. ERO is now interested in the school context, not just data on paper.”

School representatives from five of the six schools spoke positively about the way their evaluation partner worked with them. They highlighted the collegial, relational way their evaluation partner worked with the school to identify priorities to shape the focus of the evaluation.

“X (the evaluation partner) has been here 4 or 5 times. We are loving it. I get on well with x and value the conversations we are having. They are not afraid to challenge me and question me. If I didn’t get on with the evaluation partner, that would certainly make this difficult.”

The relational and interpersonal qualities the evaluation partner brings to work with the school is a core necessity in creating a successful collaborative relationship. Evaluation knowledge, skills and educational experience are also important.

One of the six schools involved in the case studies held a very negative view of the new approach on the basis of their experience of the development of their evaluation plan. The case profile below highlights how a ‘clash’ of process and expectations with the evaluation partner disrupted the evaluation process.

The evaluation partner was regarded as competent, enthusiastic and professional by both the principal and the deputy principal. However, the professional relationship became untenable and a decision was made that the evaluation partner would not continue working with the school. The experience of this school of the approach is highlighted in the following case profile.

Case Profile: St Bernard’s College, Unmet Expectations

School Context

St Bernard’s College is a state integrated Catholic school for boys from years 7-15. The school is in Lower Hutt and most students are from the area or nearby Wainuiomata. The roll is 668 students. Twenty-six percent of students identify as Māori and twenty percent of students Pacific.

The wellbeing of students throughout their journey in the school is a core focus for the staff team. The phrase ‘standing on life-giving ground’ that sits below the school banner at the entrance to the school reflects the school’s focus on creating an environment where boys can ‘stand taller and thrive and grow.’ The goal of the school is to inspire success in all students in partnership with whānau and the community.

Students are encouraged to interact and connect through mixed aged group learning opportunities and social activities.

Several buildings are being redeveloped to meet the needs of the growing school community. In 2018, the gym complex was developed with the addition of a new entrance and foyer, Physical Education classroom and specialist weights room. A new commercial kitchen was completed late in 2021. The Gregor Mendel Science Block was formally opened in 2020. The old main block is being demolished and will make way for a new purpose-built structure to be completed early in 2022.

The college's Marist Way links to the values of manaakitanga, social justice and integrity. The school focuses on: