In this paper, Timperley begins by discussing the very limited nature of the research literature relating to the impacts of external reviews, adding that this has done nothing to dampen enthusiasm for them or to slow their spread. Nearly every educational jurisdiction that has an external review system mixes both accountability and improvement purposes, setting up an inherent tension.

The author finds that ERO’s Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) includes indicators that have an effectiveness/accountability orientation and indicators that have an improvement orientation, but without differentiation. Further, it is not at all clear how the indicators work together or intersect for improvement purposes, or how they should be used to evaluate a school’s capacity to improve.

One way in which external review can permeate the layers of the school system and have an impact on classroom teaching and learning is to have it connected with and complementary to internal self-review. In New Zealand, this linkage is currently very loose, with ERO reluctant to push a specified approach onto schools that are used to managing themselves. Similarly, the linkage between our major educational agencies and their evaluation functions is loose, at a time when system coherence is needed to gain traction on major goals.

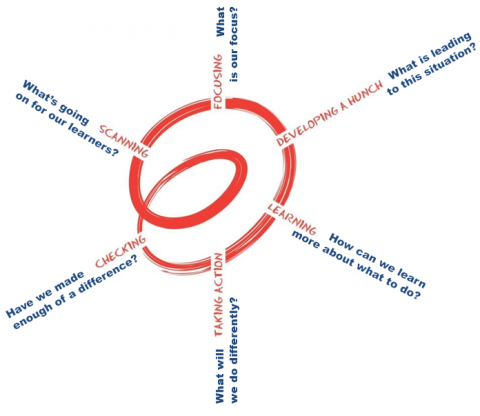

The author finds that although ERO is requiring schools to engage in cyclical self-review, it lacks a well-founded theory to explain how self-review is meant to lead to school improvement, let alone the system improvement to which it aspires. She discusses three possible models before going on to describe an ‘inquiry spiral’ with six phases: scanning, focusing, developing a hunch, learning, taking action, and checking. As always, issues of expertise and organisational capacity must be identified and addressed.

The paper concludes with a discussion of a theory for improvement through external review, with the author advocating that ERO develop a core set of indicators to be used for both internal and external review purposes.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to stimulate discussion by examining the significant influences on student learning and outcomes, the practices associated with those influences, and how these might work together to promote and support improvement in schools. A second purpose is to identify implications for the conceptual framework that underpins the Education Review Office’s current evaluation dimensions and indicators, and implications for reframing, defining and identifying indicators for a new version.

In preparing this paper I have kept in mind the persistent disparities in New Zealand’s educational profiles and the declining position of New Zealand’s educational outcomes as measured by international benchmarking surveys such as PIRLS and PISA (Mullis, Martin, Kennedy, & Foy, 2007; OECD 2010a; 2010b; 2014). While school reviews undertaken by ERO are only one part of a much bigger system picture and cannot address these issues on their own, they can have a significant influence and form part of the solution.

Given that other academic experts have been charged with parallel tasks in relation to specific dimensions of the current framework, I have had to place boundaries around my very broad remit. I begin with a brief summary of the influences on student learning and the place of external school reviews such as those undertaken by ERO. I then summarise the research findings on the conditions for external review to have an impact on student outcomes and examine the extent to which these conditions are evident in ERO’s current indicators document. Finally, I address the issue of re-reframing, defining and identifying potential indicators by proposing the development of two interacting theories for improvement. One focuses on internal self-review and the other on external review, with the aim being to explore how greater coherence across the system might be achieved.

Implications for re-framing potential indicators are drawn throughout.

Influences on student learning and the place of external review

It is well established that the most important influences on educational outcomes in any given educational context are the prior knowledge a child brings to that context, their whānau/families’ social, cultural and linguistic practices and resources, and how their teachers teach (Bruggencate, et al., 2012; Muijs & Reynolds, 2001; Nye, Konstantanopoulos & Hedges, 2004; Shouppe & Pate, 2010; Rowe & Hill, 1998). In other words, most of the variance is explained by the children themselves and those who interact directly with them. While the percentages ascribed to the contribution of these three influences vary, no statistical models contradict this fundamental premise. Beyond these immediate influences are those that have a more indirect effect, such as the schools and their leaders, and the communities in which the children live and learn.

There does not appear to be quantifiable, large-scale evidence that external school reviews such as those conducted by ERO, have an impact on learner outcomes. Indeed, Matthews and Sammons (2004) argue that it is unrealistic to assume that they will have a direct effect on school improvement. Some small scale studies, however, have identified that the evaluation process can influence the activities of leaders and teachers, given particular conditions (Ehren & Visscher, 2008; Parsons, 2006). For example, Parsons identified that the influence of the evaluation process was mediated by the evaluator, whereas the influence of the review results was mediated by the school and its community. Unless these two influences interact to permeate the layers of the system and impact on the interactions between learners and their teachers, we cannot expect much to come out of the review process. Any model and approach, therefore, must consider how this process will happen.

IMPLICATION

The influence of external review must permeate the layers of the education system in ways that effect positive changes in students’ learning environments if the review is to have an impact on outcomes for students.

Conditions that enhance the impact of external review

Although evidence for the impact of external review is very patchy, this has not stopped the rapid spread of evaluative school reviews, with their place now taken for granted in many education systems. A recent OECD report (2013) on assessment and evaluation in 15 participating countries, for example, states unequivocally:

The effective monitoring and evaluation of schools is central to the continuous improvement of student learning: Schools need feedback on their performance to help them identify how to improve their practices; and schools should be accountable for their performance. (p. 384)

This statement highlights the tension in the review process between the purposes of accountability and improvement, with the balance that is struck impacting on whether the process results in school improvement. Other conditions that influence the impact of reviews on outcomes include the linkage between internal and external review and coherence with wider system requirements.

Balancing accountability and developmental purposes

Nearly every jurisdiction that has an external review system mixes both accountability and improvement purposes. Some systems give greater emphasis to accountability; their guiding question is, “How good is the education offered in this school?” Even in the most extreme of accountability systems the intention is that judgments made will lead to improvement. The ‘No Child Left Behind’ legislation in the United States, with its emphasis on reporting yearly progress against state targets, for example, had an underlying assumption that such assessments would provide the information and motivation for schools to improve, particularly when their scores fell below the targets (Lasky, Schaffer & Hopkins, 2008 ). Most accountability-oriented systems supplement student achievement data with other indicators believed to have an impact. These additional indicators are usually grounded in the school effectiveness literature and identify, for their particular context, what is known about effective leadership, teaching, school climate and community relationships. The emphasis is on consistency of judgment, with a focus on adequacy of the education provided.

When external evaluation is framed strongly in improvement terms, the emphasis is on value-added measures and the orientation is more formative. The guiding question is, ‘In what ways has this school improved and what will support further improvements?’ The process acknowledges the place of socially constructed meaning, sense-making through interpretation and explanatory accounts.

Figure 1 summarises the different emphases in these two orientations.

|

Accountability orientation |

Improvement orientation |

|---|---|

|

Based in school effectiveness literature |

Based in school improvement literature |

|

Summative evaluation: school as is |

Formative evaluation: school as it has been or might be |

|

Outcome focus on adequacy |

Process focus and value-added |

|

Seeks to minimise variation in interpretation of results |

Embraces the social construction of meaning and emphasises interpretation |

|

Standardised measures and consistency of judgment |

Negotiated measures and mutual understanding |

Figure 1. Characteristics of accountability and improvement orientations in school review (adapted from OECD, 2013)

Given that nearly all external systems have both an accountability and an improvement function, the issue is not to have one trump the other, but to identify how they can be combined for the purposes of improving schools and outcomes for students. Some jurisdictions, such as Scotland (Education Scotland, 2011) and Wales (Estyn, 2010), make an explicit assessment about a school’s capacity to improve. As Looney (2011) identifies, it is clarity and coherence that matters.

At the extreme accountability end of the continuum are high-stakes assessments, compliance with particular requirements, punitive accountabilities and distortions rather than improvement (OECD, 2013). At the extreme improvement end of the continuum is socially-negotiated meaning without external reference or purposes, and a focus on developing positive relationships among adults that may be at the expense of a focus on improvement for students (Timperley & Robinson, 2002). I want to emphasise that accountability and improvement are both necessary for school improvement. For example, an accountability orientation can provide criteria against which to measure improvement: formative evaluation requires success criteria. Lack of consistency, where meaning is constantly negotiated, can lead to poorly performing schools receiving positive reviews.

New Zealand’s approach to purposes

Over time, ERO has shifted from what was primarily a compliance/accountability orientation to one that is more focused on improvement (Mutch, 2013). In their description of this evolutionary process, Brough and Tracey (2013) identified the tension between maintaining an accountability function for reviews while emphasising improvement purposes. The introduction to Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (ERO, 2011) states an intent to balance accountability and improvement (p. 7). This mixed heritage and the resulting unresolved tensions are evident in the document, which has ‘six dimensions of good practice’ exemplified by a mix of indicators, some of which have an effectiveness/ accountability orientation and others, an improvement orientation, without any differentiation being made between them.

Reviewers also make judgments about a school’s capacity to improve, and these influence decisions about the frequency of cycles of reviews. The criteria for these decisions are not clear in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews.

The most recent survey of school principals by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (Wylie & Bonne, 2014) provides a principals’ perspective on the developmental and accountability orientation of current ERO reviews. Improvement-oriented questions in the survey received generally positive ratings. Seventy-six percent of principals reported that ERO reviews affirmed their approach and 64% indicated they got some useful ‘fine-tuning’ advice on their systems, with 24% indicating that they saw some things in a new light which then led to positive changes in teaching and learning.

Accountability-oriented questions received a more negative response, particularly regarding consistency of judgment. Fewer than half of the respondents thought that ERO reviews were a reliable indicator of the overall quality of teaching and learning at their own school and only 23% thought that review judgments were consistent across schools. Thus it appears that socially mediated interpretive processes are given priority over consistency of judgment and accountability.

IMPLICATIONS

Develop clarity around the accountability indicators coming from a school effectiveness orientation, and the school improvement indicators coming from a schooling improvement orientation, and how they interact with one another.

Make explicit the criteria and indicators used to make judgments about a school’s capacity to improve and how these influence decisions about the timing of subsequent reviews.

Creating links between external and internal review

One way in which external review can permeate the layers of the school system and have an impact on classroom teaching and learning is to have it connected with and complementary to internal self-review systems. Research in continental Europe by Ehren, Altrichter, McNamara, & O’Hara (2012) identified that external review was likely to have a greater impact on professional activities if it was linked to internal review processes. In its review of assessment and evaluation systems in 15 countries, OECD’s Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment (2013) identifies three different kinds of linkage:

- Parallel, in which the two systems run side-by-side, each with its own criteria and protocols

- Sequential, in which external review bodies follow on from a school’s own evaluation and use that as the focus for their quality assurance system

- Cooperative, in which external agencies cooperate with schools to develop a common approach to evaluation (p. 411).

The authors of the report suggest that the parallel and sequential models imply an evaluation system that is dominated by an accountability agenda. The cooperative model implies a stronger developmental purpose.

How external and internal reviews are linked in New Zealand

An OECD report (Nusche, Laveault, MacBeath, & Santiago, 2012) finds that New Zealand has one of the strongest linkages between external and internal review, partly sequential and partly cooperative. The authors note that ERO does not prescribe methods for self-review so it does not fully meet the criteria for a cooperative system. At the same time, they note how ERO has advocated for evidence-informed inquiry and helped schools to engage in that process. Brough and Tracey (2014) confirm the extensive work that ERO has done to build the capacity of its review officers and schools’ understanding of self-review. These authors also note that:

ERO’s evaluation indicators to do with self-review were not sufficient alone to help them make sound judgements about the quality of school self-review. Nor did the indicators provide sufficient support to help Review Officers make recommendations about how schools could improve their self-review … there was a real danger of ERO prematurely prescribing to schools what their self-review should look like (p. 116).

ERO’s reluctance to specify approaches to self-review is consistent with the intent of the 1989 reforms that established self-managing schools (Education Act, 1989). These reforms were based on the belief that parents, local communities and schools are best placed to improve student learning (Fancy, 2007). While ERO has done considerable work in articulating the relationship between self-review and external systems (Brough & Tracey, 2013), it is not evident in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (ERO, 2011) apart from the broad description of a cyclic process of self-review consisting of phases of considering, planning, implementing, monitoring and informing (p. 8) through three types (strategic, regular and emergent) of school self-review (pp. 8–9).

Given the centrality of the links between external and internal review in the current system, it is important to articulate what schools are expected to be doing by way of self-review and how this relates to the external review process. A set of core indicators used across both internal and external review would create greater coherence.

IMPLICATIONS

Strong links between external and internal review give external review greater impact. Core indicators, along with frameworks and approaches that are common to both internal and external review, together with clear understandings of how the one intersects with the other, will enhance schools’ improvement efforts.

Developing links to the wider system

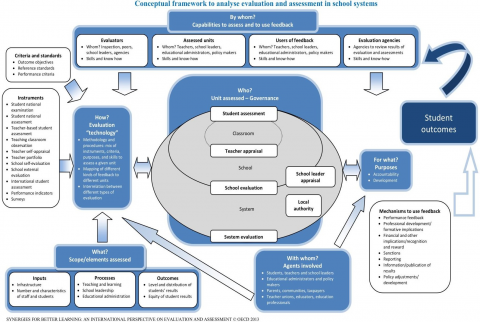

External review processes are not an island in the education system and cannot be treated as such if system coherence around important goals is to be realised across agencies such as the Ministry, EDUCANZ and NZQA. The relationship between external and internal evaluation is one system link. Other important links are identified in Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment (OECD, 2013). This report positions school evaluation systems in a wider system framework that provides coherence between the different layers of evaluation: student assessment, teacher and leader appraisal systems, school evaluation (review), and evaluation of the education system itself. A system map (Figure 2 identifies complementary purposes of evaluation at each level, how criteria and standards at each level intersect, commonalities in the terminology used, and feedback mechanisms from one level of the system to the other and across system agencies. In this way, the authors of the report argue that evaluation at each level can be mutually reinforcing and create conditions for system improvement.

Links to the wider system in New Zealand

A 2011 OECD review of New Zealand’s assessment and evaluation systems (Nusche et al., 2012) commented specifically that our education system is unusually fragmented, and that system coherence is a major issue. The authors noted that this issue exists within and across different education bodies. The Ministry of Education, New Zealand Qualifications Authority, New Zealand Teachers’ Council (as it was at the time) and Education Review Office all have evaluative functions of one kind or another, but there is little coherence among them. The Ministry requires schools to self-review in relation to charter goals; ERO also requires schools to engage in self-review. Different frameworks are used by these agencies and the evidence they draw on crosses over with other agencies and frameworks. For example, judgments about the quality of self-review may include evidence from teacher appraisal. Teacher appraisal is required by both the Ministry and the outgoing Teachers’ Council (and, very likely, its successor the Education Council), but these agencies use different criteria, developed by different groups, and have different purposes (Timperley, 2013).

Figure 2. Conceptual framework to analyse evaluation and assessment in school systems

I argue that we are unlikely to achieve the system lift we need so urgently in a fragmented system where each part remains in its silo, duplicating and dispersing improvement efforts. In the interests of achieving greater coherence, any revision of ERO’s systems and indicators, such as the one currently being undertaken, needs to link to the evaluative system frameworks used by other statutory agencies. A system map would be useful.

IMPLICATIONS

Greater coherence across the system can be achieved by ensuring that the dimensions, frameworks and indicators used by ERO are situated in and linked to the assessment and evaluation requirements of other agencies (Ministry, Education Council, NZQA) and by identifying the places of student assessment and teacher and leader appraisal in school evaluation.

One way forward: Theories for improvement

A theory for improvement comprises a set of linked ideas about processes and products that lead to specified goals, which in this case relate to improved outcomes for students. In the case of external reviews of the type undertaken by ERO, two theories for improvement are needed.

The first focuses on the features of effective school self-review systems, a prerequisite for arriving at indicators that will provide schools with benchmarks that enable consistent judgments about effectiveness. These indicators will form success criteria to which a school can aspire. They will necessarily encompass improvement dimensions to signal what schools should do when areas for development are identified.

Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) has an implicit theory for improvement embedded in it. It identifies five dimensions of good practice: teaching, leading and managing, governing, school culture, and engaging families. These dimensions interact in unspecified ways to improve student learning, engagement, progress and achievement. The theory includes the enactment of three types of self-review: strategic, regular and emergent. The document also describes a cyclical review process of considering, planning, implementing, monitoring and informing, with associated questions. What is missing is an explicit theory about the interactions within and between the dimensions, the three types of self-review and the cyclical process.

A second challenge is to identify how ERO might interface with schools to enhance their improvement processes; so we have to ask, what is ERO’s theory for improvement in relation to the indicators selected and the way in which its reviewers interact with schools?

A theory for school improvement through self-review

The evidence base about the influence of school self-review on student outcomes appears to be even more limited than research on the influence of external review. In a recent study of effective secondary schools with equitable outcomes (ERO, 2014), strong self-review systems were a consistent feature. In these schools,

A relentless drive for ongoing improvement was informed by rich data and deep analysis of that data. Decision making was evidentially based and grounded in research. (p. 10).

This process was elaborated further in a later section:

Teachers, senior leaders and the board engage with this data, analysing it to identify needs, and to monitor progress and achievements across all levels of the school. Such scrutiny leads to sound self-review processes, informed both by evidence and research, and decisions are made that better tailor programmes and initiatives to meet the needs of individual students and the school (pp. 28–29).

This report is important in that it confirms that self-review systems are a feature of effective schools, but it does not elaborate the features of these systems in sufficient detail to assist the development of indicators or models for robust self-review systems.

Another recent report by ERO (2014) on raising achievement in primary schools was more explicit in its identification of the kinds of self-review that resulted in accelerated outcomes for priority groups. These schools engaged in a cycle of review that involved identifying which students were below or well below National Standards for their year group, identifying their learning strengths and needs, and then setting priorities in relation to the school’s goals. They clearly explained the urgency to improve outcomes for these targeted groups of students and then set about responding with innovations that accelerated their learning. In contrast, schools whose students made little progress either showed little sense of urgency, or carried on offering more of the same. Not much was different.

Part of the explanation for these very different responses was the deep knowledge the more effective schools were able to bring to their innovations. This knowledge included deep understanding of progression, acceleration and the curriculum. Their improvement plans included both short-term tactical responses and longer-term strategic responses designed to build teacher and leader capability. Students, parents and whānau were involved in designing and implementing the plan to accelerate progress.

The effective schools monitored and responded to the impact of innovations, using student achievement information actively and relentlessly in their decision making. They then focused their efforts on developing comprehensive systems with embedded tools and resources to ensure that gains would be sustained and that more students and teachers would benefit from the acceleration.

These responses are consistent with the more broadly focused literature on school improvement at scale (across multiple schools). I now describe this literature briefly to inform further development of a theory for improvement to underpin this revision of ERO’s dimensions and indicators.

Evidence from schooling improvement at scale

I am drawing on the evidence relating to improvement at scale because ERO seeks to have an impact across the system, not just in individual schools.

In an analysis of the international literature, McNaughton (2011) identifies three approaches to improving schools at scale. The first focuses on implementing prescriptive programme designs with high integrity. McNaughton refers to this as ‘scaling up a product’. It involves designing the best possible programme around a particular product and implementing that programme in school after school. A problem with this approach is that early successes are rarely replicated because the contextual conditions at the start of or during the improvement effort are inevitably different.

The second approach identified by McNaughton (2011) involves locating examples of effective schools that are built on research and use best practice in school organisation and instruction. The key features of these schools are identified and then repeated in other schools. The problems with this approach are similar to those with the prescriptive programme approach, in that the initial conditions and process are rarely replicated. As a result, positive outcomes are rarely repeated. The mixed results of both these approaches have implications for school review that uses effectiveness indicators in the absence of a theory for improvement.

The third approach, which underpins much of the work of the Woolf Fisher Research Centre (McNaughton, 2011), involves scaling up a process with high integrity. This involves working with the resources of selected schools to make them better, and then growing those process solutions in other schools. Of the three models described, this approach is the closest to ERO’s self-review cycle and has demonstrated some sustained success at scale under particular conditions (Lai, McNaughton, Timperley, & Hsiao, 2009; Timperley & Parr, 2009). It involves on-the-ground problem solving rather than replicating the content of the solution, although there may be commonalities between schools in terms of the instructional programme they need. Unlike ERO’s self-review cycles, the process is highly specified. In essence, it involves collecting evidence on patterns of achievement and learning; critically examining this evidence; developing hypotheses about more effective teaching; providing targeted professional development, paying careful attention to coherence of assessment; and managing teaching resources around the change.

McNaughton emphasises that the process requires a long-term partnership between external research and development and school-based practitioners. These conditions are not possible in the context of an ERO review.

A similar evidence-informed inquiry and problem-solving approach also underpinned the Literacy Professional Development Project, which demonstrated very high effect sizes in over 300 schools over a two-year involvement. In writing, the average ES was 0.88 over expected gains, which equated to 3.2 times the expected rate of progress. In reading, the parallel result was an average ES of 0.44, which equated to 1.85 times the expected rate of progress (Timperley, Parr & Meissel, 2010). Most importantly, given our disparities in achievement, the ES for the students who started in the lowest 20% of their cohorts was 1.13 for writing (3.2 times the expected rate) and 2.07 for reading (6.2 the expected rate).

Like the third approach described by McNaughton (2011), the process was highly specified and involved on-the-ground inquiry and problem solving and did not replicate a product per se. The inquiry process was similar to that described by McNaughton. It began with a close analysis of student data and teaching practice, leading to identification of professional learning needs in literacy, followed by tailored in-class and out-of-class professional development informed by the research evidence, and constant informal and formal checking about whether changes to practice were making a difference. A feature that differentiates this process from that described by McNaughton (2011) is that those at each level of the system (teachers, leaders, facilitators and project leaders) were required to engage in a formal, evidence-informed inquiry process, in this way creating a chain of influence (Timperley & Parr, 2009). A second difference is that the researchers acted in consultancy capacity, rather than directly with schools; facilitators worked with the school leaders. However, the success of the intervention was still dependent on external assistance.

Bryk (2014) refers to school reform through inquiry as a new paradigm in improvement science. In a recent address to the American Education Research Association Annual Meeting he outlines the need to address educational challenges through iterative cycles of disciplined inquiry based on six core principles:

- Make the work problem-specific and user-centered

- Address the problem of variation in performance (diverse teachers and diverse students)

- See the complexity of the system that produces the current outcomes

- Measure both the intermediate and the longer-term outcomes in order to make adjustments

- Anchor practice improvement in disciplined inquiry

- Accelerate improvement through networked communities.

All three models described above (Bryk, 2014; McNaughton, 2011; Timperley & Parr, 2009) have evidence-informed inquiry focused on learners at the heart of the processes. They share many features with the self-review processes promoted in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011). But there are two key differences. The first is specificity: while the processes in the three models just described are highly specified, ERO (2011) says, “Schools are required to conduct their own self review, although the manner in which this is to be done is not prescribed” (p. 8). Note that prescription, which is suggestive of replication and box ticking, should not be confused with specification of key processes based on deep understanding of their importance and how they can be enacted in ways consistent with a set of principles.

The loose specification provided by ERO can lead to what (Lai, 2013) has called ‘a thousand flowers blooming’. Lai examined the ineffectiveness of this approach through a series of school improvement initiatives that used an evidence-informed self-review process with a focus on local solutions as advocated in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011). While a minority schools in Lai’s study were able to make significant gains for their students, most did not have sufficiently robust data with which to begin an evidence-informed self- review process. A similar situation was found in a much larger evaluation of schooling improvement initiatives in New Zealand (Timperley, Parr, Hohepa, Le Fevre, Lai, Dingle & Schagen, 2008). School clusters were assisted through a process of undertaking an achievement analysis on which to base their theory for improvement. They received funding over a number of years to engage in cyclical improvement efforts. The extent to which this process resulted in actual improvement was highly variable, even with the extra resources. Weak specification appears to lead to highly variable processes and outcomes.

Timperley, Kaser and Halbert (2014) have recently developed a visual representation of an inquiry spiral (Figure 3) that captures the essence of an improvement process. It is being used by the Ministry (with some adaptation) in its revised frameworks for nationally funded professional learning and development. This should help create greater coherence across agencies. How the ‘effectiveness’ indicators would interact with the ‘improvement’ indicators is described below.

Figure 3. A spiral of evaluative inquiry, learning and action for school review

SCANNING answers the question, “What is going on for our learners?” In this phase, evidence about student engagement, learning and well-being is brought to the table; the partnership obligations of the Treaty of Waitangi are kept to the fore; and the perspectives of the students and their families/whānau, as well as the professionals, are heard. SCANNING takes into consideration student engagement and well-being as well as achievement data – often these go together. In the Ministry’s work on professional learning and development, this phase is called ‘Analysing’.

The next phase is FOCUSING, because when schools have more than one focus for improvement, the time and effort involved in deep learning that makes a difference is dispersed, which typically results in little change (Lai, McNaughton, Hsaio, 2010). It is important to have challenge, but not to make the learning so challenging that it creates overload (Dumont, Istance & Benavides, 2010). During this focusing phase it is essential to set goals and targets against which to judge progress. Including additional areas can happen once the issue of focus has been addressed and the learning is transferred to other areas.

DEVELOPING A HUNCH, or a hypothesis, as described in a recent Ministry document, is where the school can consult the indicators relating to effective pedagogy, leadership, and educationally powerful connections with families/whānau to help them work out how what they are doing in these areas might be contributing to the focus issue. The question is, ‘What do the indicators tell us we need to do to address the student-related issue we have identified?’

LEARNING encompasses learning for everyone: leaders, teachers, families/whānau and students. The learning is directed to the area of focus. TAKING ACTION involves doing something different, because efforts to change deepen the learning and create the conditions for improvement in student outcomes. In this phase, the indicators for effective pedagogy, leaders, and educationally powerful connections can be used to evaluate whether the right action is being taken.

In the CHECKING phase, the question is, ‘Have we made enough of a difference?’ This means checking against the goals and targets set in the earlier phases and against the indicators used in the DEVELOPING A HUNCH phase. CHECKING must involve the students and their families/whānau, because their perspective may well be different from that of the professionals, and involving them helps build educationally powerful connections. In reality, CHECKING should occur throughout. Having decided whether enough of a difference is being made, the spiral loops around to the next phase. The process is about continuous improvement.

IMPLICATIONS

For a self-review system to have systemic impact on student outcomes, the process needs to be guided by a set of core indicators on teaching, leading, educationally powerful connections and processes for evaluative inquiry that demonstrate improvement in valued outcomes for diverse learners. These indicators would provide a common basis for reviewing all schools. Additional context-specific indicators would contribute to the overall evaluation.

Integration and coherence across dimensions and over time

Implicit rather than explicit in the models described in the previous section is the importance of achieving coherence across the different dimensions of the school’s organisation. Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, and Easton (2010) identified a strong relationship between coherence and school outcomes. They studied the reform efforts of 401 elementary schools in central Chicago between 1993 and 1997. Improved outcomes for diverse students occurred only when organisational practices connected parents, teachers, leaders and students to activities in the classroom. Schools that sustained improved outcomes:

- Built the professional capacity of the teachers

- Reached out to and involved parents and the community

- Created a safe and orderly student learning climate

- Established cohesive instructional guidance across grades and classes, supported by appropriate tools and resources

- Were driven by leaders.

Bryk et al. (2010) described these components as the essential supports for school improvement, finding that strength across all of them was necessary to create better outcomes for students. Further, if a school was weak in just one of the fourteen indicators associated with these supports, there was only a 10% likelihood of improvement.

A similar perspective on the importance of coherence was identified by Timperley et al. (2010) in their evaluation of schooling improvement across 19 clusters of schools. They focused on three dimensions of capability: instructional, organisational, and evaluative. These were extended in subsequent Ministry documents to include parents/whānau and cultural responsiveness. What was important in this work, considering the task in hand, was that in the early stages of improvement, and in schools that were struggling to make progress, the dimensions of capability operated independently of one another. For example, student data were collected, analysed and reported; teachers undertook professional development in an area of need, but that area was not integrally related to the analysis of student data; and leaders were engaged in generic leadership development. The schools that had progressed further along the development track had integrated the three areas into a more coherent inquiry. In these schools, analysis of student data was related to specific goals and targets, and progress towards them was checked regularly by leaders and teachers, and teacher and leader development was integrated, with leaders learning how to promote the professional development of their teachers in relation to the focus issue and goals/targets. In other words, school processes and structures contributed to a coherent learning system focused on important goals.

A complementary perspective on coherence was identified by O’Connell (2009) in her study of the sustainability of the Literacy Professional Development Project. Most schools in the study continued to improve their literacy gains after external support was withdrawn.

Features associated with the highest levels of sustainability included ongoing, systematic inquiry, and coherence – the instructional approaches and expertise developed in the course of the literacy professional learning were applied to new areas of development.

IMPLICATIONS

Identify how the dimensions and indicators work to improve outcomes for students.

Expertise and organisational capacity

Issues of expertise permeate all sections of this paper, but particularly this section on school self-review. Expertise is needed to engage in disciplined inquiry: to identify important problems, collect relevant and reliable data about those problems, engage in appropriate dialogue and inquiry processes with others, and to develop and enact workable solutions.

There is little point in developing a theory for improvement without an accompanying theory about the expertise required to engage with it, or it will sit on the shelf with all the other unused good ideas.

Individual expertise alone cannot bring about school change. Organisational capacity to develop appropriate systems and processes is also needed. In his speech to the American Education Research Association Annual Meeting, Bryk (2014) proposes that our earlier attempts to replicate through prescription failed for reasons of organisational complexity and capacity. Teaching has become more complex and schools have become more complex so we need to adopt approaches that allow us to iteratively test and refine our change ideas as we engage in a focused organisational learning journey.

I now turn briefly to the evaluation literature to contribute a perspective on organisational capacity. The reason for drawing on the evaluation literature is that school review encompasses both evaluation and change dimensions. Indeed, as the Oxford Dictionary (online) puts it, review is a formal assessment of something with the intention of instituting change if necessary.

Cousins and Bourgeois (2014) used a cross-case analysis of eight public sector organisations to identify three main organisational characteristics and dispositions that contributed to their ability to do evaluation and to use the findings. The first was administrative commitment, demonstrated by leaders who developed organisational policies and procedures to generate and use evidence for decision making. These procedures provided mechanisms and opportunities in an organisational culture of learning. The second comprised organisational evaluation strategies that invested in personnel and positions with evaluation responsibility. These organisations often partnered with external evaluation organisations to ensure high quality and invested in their own resident expertise. A particular emphasis was on data quality assurance, with high-quality data held in high esteem and poor-quality data not tolerated. The third was engagement with evaluation throughout the organisation, where everyone was involved in evaluative activities that helped them value data through using data. Evaluative capacity was developed across organisational members.

Preskill and Torres (1999) took a complementary but different perspective, arguing that modern organisations are moving away from rational, linear, and hierarchical approaches to managing jobs. Instead, they are turning to fluid processes and networks of relationships, employing a systems approach to how work is accomplished. They argue that complementary forms of evaluation need to be developed, and for the idea of evaluative inquiry. Evaluative inquiry involves collaborating with clients and stakeholders to identify important questions and then pursue answers, working together to carry out the inquiry and integrating the learning into work practices. Organisational systems and processes spread the learning across the organisation. These processes sound similar to those promoted through self-review.

IMPLICATIONS

School-level theories of improvement are unlikely to be realised in practice unless issues of expertise and organisational capacity are identified and addressed so that the school has the expertise and a culture of evaluative inquiry for improvement.

A theory for improvement through external review

I argue earlier in this paper that two complementary theories for improvement are needed. The first, which has been addressed above, is a theory for improvement through evaluative inquiry in internal school self-review. The second, addressed more briefly in this section, is a theory for improvement through external review.

A number of possible contributions to this second theory have already been identified. These include ensuring that review processes impact on students’ learning environments, developing clarity re accountability and improvement purposes, working on coherence between internal and external review structures and processes, and making links to the wider system.

Other pointers can be found in the schooling improvement literature reviewed above. These include being specific about the qualities of highly effective schools and their self-review systems, supporting organisational coherence rather than contributing to fragmentation of effort, promoting organisational capacity for evaluation, and developing evaluative inquiry through the school as an organisation.

As with the first theory, it is important to identify the expertise required to enact the theory for external review. In this case, the reviewers need the expertise to undertake external review in ways that enhance internal review. This includes expert understanding of the dimensions and indicators and how they interact, and it includes the relational expertise to work with schools to optimise the possibilities for improvement. Parsons (2006) identified that the extent to which the review process was perceived to assist, and assisted, each school to improve was a complex interaction between the school’s review history, evaluator practice, school conditions, and participants’ responses during the review process. The evaluation process was as important as the evaluation results in promoting school improvement, with the relational aspect being of paramount importance.

It is important for ERO to be explicit about its theory for improvement and how it intersects with schools’ self-review and evaluative inquiry, for two reasons. The first is to develop a shared understanding among reviewers and schools about how ERO thinks the two systems interact. The second is to enable the causal assumptions underpinning the theory to be tested and refined over time, thereby opening ERO’s approach to evaluative scrutiny. In this way, systemic learning across the system is enabled, increasing the possibility that we will collectively contribute to solving the urgent educational challenges outlined in the introduction.

IMPLICATIONS

A theory for improvement about how ERO’s external reviews contribute to a school’s internal capacity to improve will provide clarity for reviewers and for schools and allow the causal assumptions to be tested over time with improvement processes built into the system.

One way to bring the theories together

Development of a core set of well specified indicators will provide clarity about those features that contribute to the creation of effective schools in which student learning is given top priority, and where teaching, leading, and growing educationally powerful connections with families are all organised in pursuit of that priority.

An additional set of indicators will address improvement processes and the qualities of evaluative inquiry that enables identified issues to be effectively addressed. These indicators will have high leverage if they are used by schools for their internal self-review processes, by ERO for external review, and by other education agencies such as the Ministry – to meet planning and reporting requirements, for example. In this way, system coherence will be developed.

The development of a core set of indicators would not preclude schools developing further indicators for their own specific contexts, but it would preclude them ignoring the core.

At the time of an ERO review, school and reviewers would both make formative judgments about the school, using the core set of indicators and any context-specific indicators nominated by the school. These formative judgments would bring together the indicators for leading, teaching, developing educationally powerful connections, and engaging in evaluative inquiry. The school and the ERO team would then discuss these two formative judgments, and the evidence on which they were made, and negotiate the definitive evaluative judgment that is reported to the community. The negotiated judgment would then link to the school’s strategic and annual plans, which are required for planning and reporting to the Ministry.

References

Brough, S. & Tracey, S. (2013). Changing the professional culture of school review: The inside story of ERO. In M. Lai & S. Kushner (Eds.). A Developmental and Negotiated Approach to School Self-Evaluation. (pp. 109-126). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Bruggencate, G., Luyten, H., Scheerens, J., et al. (2012). Modeling the influence of school leaders on student achievement: How can school leaders make a difference? Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(4), 699-732.

Bryk, A. (April, 2014). Improving: Joining improvement science to networked communities. Presidential address to the American Educational Research Association. Philadelphia.

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. London, UK: University of Chicago Press.

Cousins, B., & Bourgeois, I. (2014). Cross-case analysis and implications for research, theory, and practice. In J.B. Cousins & I. Bourgeois (Eds.). Organizational capacity to do and use evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 4, 101-119.

Dumont, H., Istance, D., & Benavides, F. (2010). The Nature of Learning (pp. 35–68). Paris: OECD.

Education Review Office (2011). Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews. Wellington. Author.

Education Review Office (2014). Raising achievement in primary schools. Wellington. Author. www.ero.govt.nz

Education Scotland (2011). Arrangements for Inspecting Schools in Scotland – August 2011, Education Scotland www.educationscotland.gov.uk/Images/SchoolInspectionFramework2011_tcm4-684005.pdf.

Ehren, M., & Visscher, A. (2008). The relationship between school inspections, school characteristics and school improvement. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56 (2), 205-227.

Ehren, M.C.M., Altrichter, H., McNamara, G., & O’Hara, J. (2012). Impact of school inspections on improvement of schools – describing assumptions on causal mechanisms in six European countries. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, January 2013, Springer.

Estyn (2010). Common Inspection Framework from September 2010. www.estyn.gov.uk/download/publication/11438.7/common-inspection-framework-from-september-2010/.

Fancy, H. (2007). Schooling reform: Reflections on the New Zealand experience. In T. Townsend (Ed.). International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement (Vol. 1, pp. 325-338). The Netherlands: Springer.

Lai, M. (2013). A thousand flowers blooming: The implications of school self-review for policy developers. In M. Lai & S. Kushner (Eds.). A Developmental and Negotiated Approach to School Self-Evaluation. (pp. 57-72). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Lai, M., McNaughton, S., Hsaio, S. (2010). Building Evaluative Capability in Schooling Improvement: Milestone Report Part B: Strand Two. Report to the Ministry of Education, Wellington.

Lasky, S., Schaffer, G., & Hopkins, T. (2008). Learning to think and talk from evidence: Developing system-wide capacity for learning conversations. In L. Earl & H. Timperley (Eds.). Professional Learning Conversations: Challenges in Using Evidence for Improvement. (pp. 95-108). Springer Academic Publishers.

Looney, J. (2011). Alignment in complex systems, achieving balance and coherence. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 64, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/edu/workingpapers.

Matthews, P., & Sammons, P. (2004). Improvement through inspection: An evaluation of the impact of Ofsted’s work, Crown Copyright.

McNaughton, S. (2011). Designing better schools for culturally and linguistically diverse children: A science of performance model for research. New York: Routledge.

Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2001). Effective teaching: Evidence and practice. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Mullis, I., Martin, M., Kennedy, A., & Foy, P. (2007). IEA’s Progress in International Reading Literacy study in primary school in 40 counties. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMMS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

Mutch, C. (2013). Developing a conceptual framework for school review. In M. Lai & S. Kushner (Eds.). A Developmental and Negotiated Approach to School Self-Evaluation. (pp. 91-108). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Nusche, D., Laveault, D., MacBeath, J., & Santiago, P. (2012). OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education: New Zealand 2011. Paris, France: OECD. doi:10.

Nye, B., Konstantanopoulos, S., & Hedges, L.V. (2004). How large are teacher effects? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 26(3), 237-257. O’Connell, P. (2009). Is sustainability of schooling improvement an article of faith or can it be deliberately crafted? Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Auckland.

Parsons, R. (2006). External evaluation in New Zealand schooling. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Preskill, H., & Torres, R. (1999). Building capacity for organizational learning through evaluative inquiry. Evaluation, 5, 42-60.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2010a). PISA 2009 results: Overcoming social background - Equity in learning opportunities and outcomes (volume II). Paris, France: Author. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264091504-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2010b). PISA 2009 results: What students know and can do - student performance in reading, mathematics and science (volume I). Paris, France: Author. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264091450-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, doi: 10.1787/9789264190658-en.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2014), PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do – Student Performance in Mathematics, Reading and Science (Volume I, Revised edition, February 2014), PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, doi: 10.1787/9789264201118-en.

Rowe, K. J., & Hill, P. W. (1998). Modelling educational effectiveness in classrooms: The use of multilevel structural equations to model students’ progress. Educational Research and Evaluation, 4(4), 307-347.

Shouppe, G., & Pate, J. L. (2010). Teachers' perceptions of school climate, principal leadership style and teacher behaviors on student academic achievement. National Teacher Education Journal, 3(2), 87-98.

Timperley, H., Kaser, L., & Halbert, J. (2014). A framework for transforming learning in schools: Innovation and the spiral of inquiry. Seminar series 234. Melbourne: Centre for Strategic Education.

Timperley, H., & Robinson, V.M.J. (2002). Partnership: Focusing the relationship on the task of School Improvement. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Timperley, H., Parr, J., Hohepa, M., Le Fevre, D., Lai, M., Dingle, R., Schagen, S. (2008). Findings from an Inventory Phase of the Building Evaluative Capability in Schooling Improvement Project, Report to the New Zealand Ministry of Education, Wellington, New Zealand.

Timperley, H., Parr, J., & Meissel, K. (2010). Making a difference to student achievement in literacy: Final research report on the Literacy Professional Development Project. Report to Learning Media Ltd., Wellington, New Zealand.

Timperley, H. (2013). The New Zealand educational context: Evaluation and self-review in a self-managing system. In M. Lai & S. Kushner (Eds.). A Developmental and Negotiated Approach to School Self-Evaluation. (pp. 23-39). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Timperley, H., & Parr, J. (2009). Chain of influence from policy to practice in the New Zealand Literacy Strategy. Research Papers in Education, 24(2), 135-154.

Wylie, C., & Bonne, L. (2014). Primary and Intermediate Schools in 2013. Wellington: NZCER.