In this paper, the author describes how the current widespread interest in indicators of education quality is the result of three converging strands: school effectiveness research, school improvement research, and information technology. From the beginning there has been a tension between the use of indicators for accountability and improvement purposes; where the balance is struck significantly influences the indicators themselves, how they are organised in domains, and how they are used in practice. Illustrative examples are provided from different jurisdictions.

The paper discusses aspects of the New Zealand schools context and how ERO’s focus and engagement philosophy have changed over time before going on to describe and critique its current evaluative framework and indicators. Earl finds that the current system is ‘very sophisticated, with multiple layers’, and that it provides detailed descriptions of what one could expect to see in a ‘high-quality’ school. She deduces that the current evaluative questions, domains and ‘massive number’ (278) of indicators derive from a broad scan of the school effectiveness and improvement literature. An issue is that the indicators are not differentiated in terms of value or importance. While ERO states a variety of purposes for the indicators, it gives little direction about how they should be used.

The author identifies several issues to be considered as the current system is reviewed. The first is the need to clarify orientation (accountability vs improvement), as this will influence how review is approached, what reviewers pay attention to, and how a review is used. The second is the lack of an overarching theory of change to provide structure and direction for schools/external reviewers. The third is evaluative capacity: good data-based decision making requires a considerable level of statistical skills and understanding.

Introduction and remit

This paper is one of a series of expert reviews that form part of an internal review and update of the Education Review Office (ERO) Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews. This particular paper addresses considerations in the framing, definition, identification and selection of indicators of education quality and their potential use in school evaluation. In it, I examine various ways in which school review indicators are understood, determined and used in the international literature, provide an overview and critique of the way in which they are presented in the New Zealand context, and raise some issues related to the creation and use of indicators that may be useful to ERO in its deliberations.

Framing indicators of school quality

For many years, school evaluation focused on compliance with policies and regulations, with little attention being paid to school-level processes. School quality indicators that attended to both outcomes and processes came to the fore in the 80s and 90s, with the recognition that education was a major contributor to the economic health of nations and a political imperative to enhance productivity. At the same time, a longstanding belief that family background was the primary contributor to student achievement was challenged by school effectiveness research.

Researchers in countries as diverse as England, Canada, the US, the Netherlands, Cyprus, and Australia (e.g., Rutter et al., 1979; Mortimore et al., 1988; Lezotte, 1991; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008) made it clear that, although family background was important, schools can and do make a difference in student performance. Large-scale school effectiveness studies identified a range of correlates within the control of schools that contribute to achievement and success for the students who attend them.

The advent of technology that made it possible to collect and organise data about schools in a wide range of ways gave educators, policy makers and researchers the tools to systematically gather data to measure the quality of schools. These advances in research and technology set the stage, and because they came at a time of increasing concern about the quality of education, data-based decision making in education was picked up in a pervasive movement towards large-scale school reform. Around the world, nations, states, provinces and school districts engaged in school reform efforts involving large-scale assessment systems, indicators of effectiveness, targets, and inspection or review programs. Rewards and sanctions were often tied to results and various combinations of the foregoing (Whitty et al., 1998; Leithwood, Edge & Jantzi, 1999).

School effectiveness research ran parallel to another strand focused on school improvement. Knowing the factors associated with a school that is already effective does not provide information about how schools can move from being ineffective to being effective. As Hopkins (2001) defined it, school improvement is a distinct approach to educational change that aims to enhance student outcomes as well as strengthening the school’s capacity for managing change. However, the simplicity of the definition belies the complexity and the challenges associated with using the correlates of school effectiveness to travel on a trajectory of effectiveness over time. Gray et al. (1999) suggested that school improvement is a sustained upward trend in effectiveness. An improving school is one that increases its effectiveness over time – adding ever greater value for its students. To be effective, improvement efforts require vision, monitoring, planning, and performance indicators.

Many years of school improvement research have shown us that changing schools in a sustainable way is hard work. Interventions that tinker around the edges have limited effects on achievement (Coburn, 2003; Elmore, 2004). Even if achievement levels do improve, the gap between the most and least advantaged often remains far too wide. A multitude of researchers, policy makers and practitioners world-wide have dedicated their working lives to understanding how educational change works, and to helping educators and systems change through the use of learning from both the school effectiveness and school improvement research (e.g. leadership, professional learning, student involvement, high expectations, etc.).

These two traditions have increasingly worked together, with school improvement researchers drawing on the school effectiveness knowledge base to leverage factors that may be manipulated or changed to produce higher-quality schooling, and school effectiveness researchers investigating the empirical linkages between these factors and testing how they work together in practice. The two fields do, however, differ when it comes to the defining, selecting and using of school quality indicators.1

This paper focuses particularly on the nature and role of school quality indicators. The avowed purpose of indicators is typically twofold: to improve schools and to hold schools accountable, with many variations on where the balance is struck. Although these purposes are both laudable, the process does not happen outside the political and cultural context of particular societies and schools. Wherever quality indicators have been used there have been differing philosophies about the nature of the evidence that should be used and how it should be used to enhance the education system and outcomes for students. The language of improvement and of accountability is always filtered through the policies, expectations, and decision-making processes of the jurisdiction concerned.

Defining indicators

When in the early 90s Shavelson, McDonnell and Oakes (1991) took on the task of defining educational indicators in the US, they pointed out that the term ‘indicator’ typically meant a statistic. But following a review of the literature on social indicators they concluded that indicators were “anything but clear and consistent” and argued that the definition be left open so that indicators could be arrived at on pragmatic grounds and draw on both quantitative and qualitative data. This ‘mixed’ interpretation continues to be influential: whatever the jurisdiction, school quality indicators and their use derive from the local political and historical context, the available data, the intended uses, and the process for engaging with the evidence. Defining the nature of an indicator process involves establishing the purpose for the indicators, what form they will take, what domains to use, and a process for using them for the intended purposes.

Educational indicators are used for many different purposes at the international and national level. In the OECD’s Education at a Glance, indicators provide nation-level quantitative data regarding, for example, the impact of education on macroeconomic outcomes, the specific factors that influence the level of education spending in different countries, the makeup of the teaching force, and training required for entering the teaching profession. Conditions of Education, produced by the US National Council of Educational Statistics, uses indicators to gather nation- and state-level data regarding enrolment trends, distance education, school climate, revenue sources, and school dropout rates.

School monitoring and review is now a regular process in many school systems, taking different forms and having different emphases. The country reports in the recent OECD study on Assessment and Evaluation provide an invaluable resource on the approaches used by different countries.2 The summary report of this study says ‘educational measurement and indicators development are rising in importance’, and that there is increasing focus on measuring student outcomes. The authors go on to say that:

… for the purpose of monitoring education systems and evaluating school performance, data are increasingly complemented by a wide range of education indicators based on demographic, administrative and contextual data collected from individual schools (OECD, 2013, p. 6).

The focus of this paper is the use of indicators within a monitoring and review process, with particular attention to the purpose of the reviews. Schools can be systematically reviewed for reasons of accountability, in which case evidence is gathered about the quality of education in and across schools, or for improvement purposes, in which case a school’s effectiveness is monitored as a foundation for changes in practice and procedures. In many places reviews serve both purposes, using a variety of processes, both internal and external, to consider evidence derived from a range of sources.

The balance that is struck between accountability and improvement often influences the kinds of indicators that are developed and how they are used in the school review process. In an accountability environment, the emphasis is typically on creating statistics or measures to represent the attributes to be reviewed. Reliability and validity are essential in any comprehensive review of schools where an accurate picture is wanted in relation to identified dimensions. These statistics are often generated centrally and constitute the template for reporting; they may be augmented by qualitative data and observation in individual schools. There is a focus on collecting, organising and reporting data to provide a valid and reliable picture of the state of affairs. When improvement is the focus, some indicators may be statistical, but qualitative as well as quantitative evidence is valued. What matters now is making sense of the evidence, establishing hypotheses, and going deeper – not just to clarify how a school is doing, but to provide a foundation for change.

Identifying and selecting school quality indicators

As mentioned earlier, every indicator system operates within a context. However, there is a long history associated with indicators, and this history is important for understanding and utilising them. Evaluating the quality of schools is a complex task. Although improved student outcomes is obviously the goal, focusing only on outcomes can provide a narrow and flawed picture of the school’s influence, as school effectiveness research shows.

Stufflebeam (1983) proposed a framework for evaluations, particularly those aimed at effecting long-term, sustainable improvement, as a means of identifying areas that can be improved. The framework treats education as a dynamic system and shows the relationships between the various domains. It recognises the influence of culture and family background, together with school processes and activities, in determining how well students achieve. It does so by paying attention to context, input, process and product (CIPP).

The CIPP framework guided the work of many researchers as they set out to determine which school-level processes were most salient in effective schools. These school effectiveness studies generated an understanding of the characteristics of effective schools. Although the research resulted in somewhat different characteristics being identified, a comprehensive analysis by Teddlie & Reynolds (2000), based on hundreds of ‘process based’ studies, identified nine similar, empirically-derived global factors that are related to effectiveness in schools.

School quality domains have been determined in other ways as well. MacBeath et al., (1995) asked teachers, parents, pupils, support staff, governors and senior management teams in a sample of schools to provide their own indicators of a good school. Subsequent analysis revealed domains that were similar to those derived from school effectiveness research, as well as others that were locally important.

School Effectiveness Characteristics (Teddlie & Reynolds, 2000

1. Effective leadership that was:

- Firm

- Involving

- Instrumentally orientated

- Involving monitoring

- Involved staff replacement

2. A focus upon learning that involved:

- Focusing on academic outcomes

- Maximized learning time

3. A positive school culture that involved:

- Shared vision

- An orderly climate

- Positive reinforcement

4. High expectations of students and staff

5. Monitoring progress at school, classroom and student level

6. Involving parents through:

- Buffering negative influences

- Promoting positive interactions

7. Generating effective teaching through:

- Maximizing learning time

- Grouping strategies

- Benchmarking against best practice

- Adapting practice to student needs

8. Professional development of staff that was:

- Site located

- Integrated with school initiatives

9. Involving students in the educational process through:

- Responsibilities

- Rights

First, any jurisdiction must identify ‘what matters’ sufficiently to be worth including in the review process, paying attention to what is known from research and to unique contextual factors such as local policy initiatives or issues of compliance with policies and regulations (e.g., finance, governance, equity).

I include several examples below to illustrate the differences that exist in different jurisdictions. In the Netherlands, the quality domains and sub-domains focus on outcomes, teacher quality, teaching and learning, care, finance and policy compliance.

The Netherlands quality domains from the inspection report for primary schools

|

Quality domain |

Quality aspects |

|---|---|

|

Outcomes |

Learning results in basic subjects Progress in student development |

|

Teaching personnel policy |

Requirements with respect to competencies Sustainable assurance of the quality of teaching personnel |

|

Teaching and learning |

Subject matter coverage Time Stimulating and supportive teaching and learning process Safe, supportive and stimulating school climate Special care for children with learning difficulties The content, level and execution of assessments and exams |

|

Quality care |

Systematic quality care by the school |

|

Financial compliance |

Financial continuity Financial compliance |

|

Other legal requirements |

Law on parent participation in school decisions (e.g.) |

Schools obtain core statistical information on their own functioning (e.g., financial, attendance, student achievement on tests, etc.) from a central agency and are supported to create their own indicators based on, for example, parent satisfaction with the school (Scheerens et al., 2012).

For each of the quality aspects a number of process indicators are specified, for example:

- The school systematically evaluates the quality of learning outcomes and teaching and learning processes

- The school uses a coherent system of standardized tests and procedures for monitoring student achievement and development

- Teachers systematically monitor and analyse student progress

- Subject matter coverage is such that it prepares pupils for secondary education

- Subject matter coverage is integrated

- The school knows the educational needs of its school population

- Learning time is sufficient for the students to master the subject matter

- The school programs sufficient teaching time

- Teaching activities are well structured and effective

- Teachers take care of their teaching, being adaptive to the learning needs of the students

- School staff and pupils interact in a positive way

- The school stimulates the involvement of parents.

The government conducts an annual risk analysis to target inspection visits to potentially failing schools. All schools are required to do a self-evaluation every four years. An internal supervisory board that includes community members is charged with approving/authorizing the school’s annual report, monitoring the extent to which it meets legal requirements, and supervising its codes of conduct and financial management. Schools are also required to meet minimum student achievement levels: national standardized tests evaluate the extent to which students are meeting core objectives and attainment benchmarks.

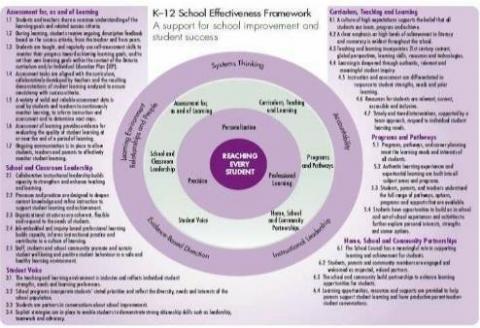

In Ontario, Canada, the Ministry of Education has developed a School Effectiveness Framework that describes dimensions that impact on student achievement:

- Assessment for, as and of learning

- Curriculum, Teaching and Learning

- Programs and Pathways

- Home, School and Community Partnerships

- Student Voice

- School and Classroom Leadership.

The School Effectiveness Framework is used by schools as the foundation for an annual self- review and their school improvement plans, and by districts for periodic external reviews conducted by teams of peers. Data generated centrally is available to schools.

These two examples show different definitions of the scope or domains of a school review process. Although both include internal and external review processes, the balance is different and the type of evidence they draw on is rooted in the designated domains: the Netherlands places greater emphasis on accountability, measures of compliance, and reliance on data from the central data system; Ontario places greater emphasis on processes associated with school effectiveness, and central data are used to support deliberations. In both cases, process indicators are framed as statements of activities or processes that reviewers, whether internal or external, should be able to observe and use to inform judgements. Both these examples are of systems where the review process is both internal and external; one focuses primarily on accountability and the other on improvement.

Creating an evaluation framework requires a logical process to be followed to identify and define indicators. It will be deeply dependent on context and on the orientation that the system chooses to adopt. Some indicators are empirical and quantitative, and are used to characterize the nature of a system in terms of its components – how they relate and how they change over time. Other indicators are rational rather than empirical and provide localised, context-specific information.

Uses of school quality indicators

As I have mentioned, indicators of quality are used for accountability, for improvement, and for both. For the most part, the designated domains are the same; what differs is how the participants are oriented to the purpose of the review and how they engage with the evidence: how they view the purpose will dictate how the information is collected, analysed, interpreted and used.

When a review has an accountability orientation, the focus is on identifying how well a school is or is not succeeding in relation to the dimensions described by the indicators. Evidence collected is likely to be organised as scores or ratings for the different domains and then analysed by people external to the school. Data are likely to be interpreted against a past benchmark or compared with data from other institutions as a means of determining what progress is being made towards a designated goal or standard (Shavelson, McDonnell & Oakes, 1991). Data may come from central data sources, from external reviewers using a rubric, or be collected locally (e.g., surveys, focus groups, documents, observations). Raters may generate scores on a scale or a rubric, or they may form a reasoned judgment as to where a school is on some, perhaps undefined, continuum of quality. Reports are typically generated by the external reviewers (sometimes in collaboration with school personnel). Schools receive the reports with summaries of the various indicators and comments from the reviewers, and they use these reports to develop an action plan.

When a review has an improvement orientation, the focus is on understanding how the dimensions represented by the indicators are evidenced in a school and then using the understanding gained to bring change to areas that emerge as important. Approaches to school improvement are increasingly driven by a theory of building professional capital as described by Hargreaves & Fullan (2012), where the emphasis is on building up the expertise of teachers individually and collectively so that they can make a difference to the learning and achievement of all students. The review process is seen as a professional responsibility and indicators form the basis for the work, with school personnel at the core of the review team – gathering the evidence, reflecting on what it means and challenging their beliefs and their practices, as a routine part of their professional work. In this case reports are generated by the school, with input and advice from external experts, as part of a planning process, and they are routinely updated and revised as it makes changes and collects additional evidence of progress.

In most systems the review process is intended to serve both purposes, but the stated and actual uses are not always well aligned. Sometimes the accountability purpose can cloud and distort the improvement purpose. Sometimes the improvement purpose amounts to little more than a superficial reporting exercise instead of being core school business.

School review indicators in New Zealand

The Education Review Office was set up as part of the Tomorrow’s Schools reforms to monitor schools and report to the community, families and whānau. Self-review is embedded in every school’s charter, with a provision for periodic external reviews by an ERO team. Both internal and external, reviews are a means of identifying, monitoring and evaluating how effectively schools are meeting the diverse needs of their students. They provide a basis for action, and for recognising and sustaining good practice. Schools are expected to ensure that their students achieve throughout their schooling and that they gain the knowledge, competencies and dispositions that will enable them to succeed in life. In this way, student engagement, progress and achievement are indirect measures for the wider goal of the confident, connected, New Zealand citizen of the future. (ERO, 2011)

Framing

In New Zealand, school review is situated in a context of self-management and local accountability, where decision making is located as close as possible to the point of implementation and a high level of trust is invested in schools and school professionals (Timperley, 2013). Central to this system is “a partnership between the professionals and the particular community in which [the school] is located”, with decisions about and accountability for personnel, quality, assessment and goal setting in the hands of the local school board. ERO was established as a moderator of this localism, with responsibility for monitoring and reporting on compliance with legal requirements, and reviewing the quality of education offered (Timperley, 2013).

This process has evolved over time, as has the New Zealand educational policy context. ERO has moved beyond periodic auditing for accountability purposes to requiring routine school self- evaluation, supplemented by periodic external review, as a collaborative and negotiated process. This complementary process, in which ERO is viewed as a partner, combines external review with the generative power of self-review (Mutch, 2013). ERO’s reviews provide information to schools to be used for improvement purposes, and to the public, via freely available online reports. Schools are encouraged to engage in self-review of various kinds (strategic, regular and emergent), paying attention to current status, using data as a routine activity, and using evidence to determine progress towards goals and next steps. The questions, prompts and indicators in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (ERO, 2011) are intended to guide both internal self-review and external review, supporting schools and ERO teams to focus observations, gather appropriate data, synthesise findings, make judgements and frame reports.

Equity is a major policy focus in New Zealand education. Schools are required to attend to the diverse needs of their students and raise achievement, particularly that of Māori and Pacific students, and those with special needs. This goal requires a coordinated approach across all domains of teaching, assessment, community relations, curriculum, resource allocation, communication, leadership and management (ERO, 2011).

This context frames the requirement for schools to conduct self-reviews, collect information about, and report on the achievement of students, paying particular attention to Māori and Pacific students and those with special needs. As part of self-review, schools are expected to use data to evaluate the success of their curriculum and teaching programmes, to inform strategic planning and school development, and as the basis for charter goals and objectives relating to student outcomes (charters are submitted to the Secretary of Education for approval).

Although the focus of self-review is improvement, accountability requirements are met by the periodic ERO reviews (reports are posted online and shared with the local community). Where there there are concerns, schools are reviewed more frequently until the issues are resolved. Results are not aggregated across schools to be reported for groups of schools or nationally.

Definition

ERO’s indicators system is very sophisticated, with multiple layers. The conceptual framework found in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) includes six dimensions of good practice that schools are expected to use when self reviewing:

- Student learning: engagement, progress and achievement

- Effective teaching

- Leading and managing the school

- Governing the school

- Safe and inclusive school culture

- Engaging parents, whanau and communities.

Each of the six dimensions is related to the other five, with student learning (engagement, progress and achievement) being central and the others playing support roles. Each is introduced by four to seven questions that make the intentions of the dimension clear and set the parameters for the evaluation. Each evaluative question is associated with several evaluative prompts, and for each prompt there are multiple ‘examples of indicators’. The indicators should not be understood as a checklist of ‘look fors’; rather, they are examples of behaviours, practices and dispositions that might be observed in classrooms and schools (via a range of data sources). All have some relationship to quality in schools. They are not statistics, nor are they derived empirically; they are the outcome of a rational process, less a form of measurement than a series of desirable characteristics.

The dimensions, evaluative questions, prompts, examples of indicators and possible sources of data provide rich, detailed descriptions of what one could expect to see in a ‘high-quality’ school. The aim is to assist schools to ask questions that focus on aspects of practice that are known to contribute to engagement, progress and achievement.3 The expectation is that school personnel will use these supports to help them gather relevant data, use professional judgment to evaluate the current state of affairs in a range of areas, examine their own practice in relation to these evaluations, plan and execute actions designed to enhance student outcomes, and to provide the basis for conversation with the ERO review team.

Identification

The dimensions, evaluative questions and indicators in Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) appear to have been identified through a broad scan of the school effectiveness and school improvement literature. This literature has been used to construct evaluative questions and to devise examples of ‘ideal’ practice as indicators. The indicators have been chosen rationally to represent the dimensions and evaluation questions, based on the writers’ interpretation of the literature and its relevance to New Zealand. The documentation provides plain language definitions of quality and rationales for the inclusion of the different indicators, but it does not identify their relative importance.

As the following table shows, the result is a massive number of indicators (278) providing examples of how a school’s quality might be demonstrated across the six dimensions.

Dimension: Student learning

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Achievement |

6 |

|

Progress |

3 |

|

Engagement |

11 |

|

Māori students |

5 |

|

Pasifika students |

5 |

|

Diverse students |

8 |

|

Quality of data/analysis |

4 |

|

Reporting to parents, whānau and community |

9 |

Total: 51

Dimension: Effective teaching

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

High expectations |

4 |

|

Teacher knowledge |

6 |

|

Match to student knowledge |

6 |

|

Wide range of teaching methods |

7 |

|

Learning environment |

4 |

|

Classroom management |

6 |

|

Formative assessment |

5 |

|

Use of assessment data |

3 |

|

Teaching for Māori students |

5 |

|

Te reo/bicultural awareness |

1 |

|

Teaching and learning resources |

5 |

|

Teacher reflection and support |

4 |

Total: 56

Dimension: Leading and managing the school

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Goals and expectations |

6 |

|

Strategic resourcing |

3 |

|

Curriculum coordination, design, evaluation |

8 |

|

Coordinating and evaluating teaching |

7 |

|

Leadership opportunities |

4 |

|

Promoting professional learning |

7 |

|

Management that supports learning |

4 |

|

Self-review |

3 |

|

Analysis and use of assessment data |

3 |

|

Links with the community |

5 |

Total: 50

Dimension: Governing the school

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Vision and values |

4 |

|

Strategic planning |

7 |

|

Use of achievement data |

3 |

|

Self-review |

4 |

|

Allocation of resources |

6 |

|

Board operation and management |

4 |

|

Performance management |

5 |

|

Leadership opportunities |

1 |

|

Whānau and community relationships |

5 |

Total: 39

Dimension: Safe and inclusive school culture

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Safe physical environment |

3 |

|

Safe emotional environment |

10 |

|

Respectful relationships in an inclusive culture |

10 |

|

Focus on learning in a positive environment |

10 |

|

Including Māori students and whānau |

5 |

|

Including diverse students |

5 |

Total: 43

Dimension: Engaging parents, whānau and community

|

Headings |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Gathering information from the community |

3 |

|

Using information in making decisions |

3 |

|

Forming partnerships with parents and students |

10 |

|

Engaging parents and whānau |

9 |

|

Engaging the Māori community |

5 |

|

Engaging Pacific and other community groups |

4 |

|

Relationships with the larger community |

5 |

Total: 39

OVERALL TOTAL: 278

The scanning and identification of indicators appears to have been conducted, and the results collated and organised, by ERO personnel, and then vetted by stakeholders. But there is no indication of how the consultation with stakeholders occurred.

Selection

The documentation does not differentiate the indicators in terms of value or importance. Each school is free to design its own internal review process and, as part of this, to select what indicators and sources of evidence they will use, within the framework. This allows schools to focus their planning and investigate pertinent areas more deeply. It also provides a basis for ERO to judge how effectively a school is using evidence to guide its decision making.

With almost 300 indicators, this process could be daunting, particularly as there is no direction in the documentation about how the indicators should be used, or even key indicators to be addressed (although government priorities are identified). While there are advantages in allowing schools to focus on their own priorities, there is a risk that schools may pay trivial attention to issues that are easy to address while they overlook others that are more difficult or intransigent.

Uses

How indicators are considered and used is at the heart of decisions about the school review process. New Zealand has opted for a mixed purpose system, with self-reviewing as a charter obligation and ERO conducting periodic external reviews to quality assure the process and support change in schools. These reviews are seen as complementary, with self-review providing the basis for a school-wide vision and improvement priorities (related to curriculum, government policies, and community aspirations) and the ERO providing external oversight and support.

The specific purposes of the evaluation indicators are to:

- assist ERO reviewers to consider what is significant when making judgments about quality education

- keep the reviews focused on students and their engagement, progress and achievement

- keep the importance of high quality outcomes for Māori students to the fore

- assist schools to meet the needs of their diverse groups of students

- make the review process transparent and consistent in quality

- assist ERO reviewers to pinpoint aspects where a school needs to improve

- assist ERO reviewers to provide feedback to schools on areas of good practice

- articulate for schools the basis on which the judgments are made

- provide a tool to assist schools to conduct their own self review

- build evaluation capacity in schools by modelling evaluative questions and evidence based judgments.

During an ERO review there are discussions between ERO and the school about which evaluative questions, prompts or indicators should be used, and about the interpretation of data gathered. These discussions are intended to assist developmental thinking and lead to a shared understanding about the basis of evaluative judgments (ERO, 2011).

- The six dimensions of good practice can be used to highlight important aspects of school life, their relationship to each other and to student achievement and self-review.

- The key evaluative questions can be used to open up discussion on the factors that contribute to each dimension. Reviewers can use these overarching questions to guide ERO education reviews and explain to schools that these questions can be used to design their own self review.

- The evaluative prompts break down the key evaluative questions into aspects that can be used to guide the gathering of evidence.

- The indicators provide statements of good practice, that is, what ERO would expect to see in a high performing school. The indicator statements are useful, therefore, in describing a school’s good practice or in highlighting aspects that need more attention.

Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) provides a great deal of contextual information and examples of possible data sources to support both internal and external reviewing. While it provides rich images of the ‘ideal’ school, it does not give reviewers (whether ERO or school) specific direction concerning the general orientation of the review process towards accountability or improvement, nor does it provide much guidance about how to engage with and use the information in the document.

Issues for consideration

Getting the use of indicators within a review process ‘right’ is an issue for many countries and jurisdictions, not just New Zealand. The authors of Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment (OECD, 2013) identified five issues associated with school evaluation that were relevant across countries:

- Aligning the external evaluation of schools with school self-evaluation

- Ensuring the centrality of the quality of teaching and learning

- Balancing information to parents with fair and reasonable public reporting on schools

- Building competence in the techniques of self-evaluation and external school evaluation

- Improving the data handling skills of school agents.

New Zealand has been involved in addressing these issues for some time now and continues to do so. The ERO review process is robust and covers a lot of territory. Both internal and external reviews follow the same general documentation and process; the documentation provides in- depth descriptions of the dimensions to be considered to establish quality, and the documentation attempts to address both accountability and improvement. I now turn my attention to several issues that I believe require careful consideration as part of this expert review and update.

Clarity of purposes

Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews (2011) provides a background rationale, set of principles and purpose statement for the use of indicators, but it does not provide a clear statement concerning how a review fits the broader policy landscape, how it relates to other directives, and what purpose should drive and guide reviewers (whether internal or external). This clarification is particularly important, because, while a stronger accountability agenda has emerged in most areas of the system in recent years, ERO has moved in the opposite direction, away from what has been primarily an accountability/compliance orientation and towards a differentiated improvement orientation, where school self-review and external evaluation are much more closely integrated (Timperley, 2013). Schools that are not performing well receive increased support over time to increase evaluation capacity. This undoubtedly creates a tension, as Nusche et al. (2012) have identified:

The requirements for planning and reporting to the Ministry described above are not necessarily integrated with the self-review systems promoted by the Review Office.

This tension is not necessarily a problem, but it does require that ERO establish its orientation. As I mentioned earlier, the orientation that participants bring to the evidence and to the whole review process has a major influence on how they define their task and how they engage. This orientation towards balancing improvement and accountability is cultural and cognitive, not merely technical. It manifests itself in how the school and ERO approach the review process, what they pay attention to, and how they end up using the review. ERO needs to be clear and explicit about the purpose of the indicators and provide schools and ERO reviewers with guidance about how process is intended to interface with and complement other policy directions.

Balancing accountability and improvement

As already discussed, most indicator systems, including ERO’s, purport to address both accountability and improvement. In the New Zealand context, the likelihood that there will be alignment between internal and external reviews is enhanced by the use of the same framework and indicators and the provision of detailed images of effectiveness. As they stand, however, ERO’s indicators do not serve either the accountability or the improvement purpose as well as they might. These purposes are not mutually exclusive, but a review process must be framed very carefully to ensure that it adequately serves both.

If the primary purpose is improvement, ERO’s indicators provide a good start, but they leave the job far from finished. The multitude of ideas and indicators creates an almost overwhelming challenge for schools as they consider what to focus on in their review. The problem is not so much the number as the lack of an organising theory. Our current understanding of how people learn (Bransford, et al., 2000) makes it clear that ideas need to be organised into a conceptual framework that allows people to connect them to a bigger idea and apply them in new contexts. Although ERO’s indicators are grouped within dimensions, there is no overarching theory of change to provide structure and direction for their use. As a result, schools are likely to attend to indicators in isolation, often superficially, rather than ground their reviewing in a theory of change that coordinates and guides the collaborative process of gathering, considering and interpreting evidence, with the aim of changing practice in ways that enhance outcomes for students.

Twenty-five years of school improvement research shows that changing schools depends on internal capacity and new learning. It requires motivation (improvement orientation) new knowledge, and the development of new skills, dispositions and relationships. Using indicators as a mechanism for improving practice depends on skill in using data, creating cultures of inquiry, engaging in deep and challenging conversations about practice, and changing long- established beliefs and patterns of practice. Considered this way, indicators and the review process itself are tools to support the thinking and action that is part of building professional capital (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). Professional capital comprises three kinds of capital: human capital (the talent of individuals), social capital (the collaborative power of the group), and decisional capital (the wisdom and expertise, cultivated over many years, to make sound judgments about learners). ERO’s indicators approach has the potential to provide important and timely information related to the building of professional capital, but achieving this will take high levels of planning expertise and data literacy, and the approach will need to be framed and used as a constant companion in all school improvement endeavours.

If the primary purpose is accountability, indicators are typically intended to provide a measure of effectiveness that has some consistency and credibility within and across schools. Although ERO’s indicators are not (and need not be) expressed as statistics, they are likely used as a mental checklist by reviewers as they consider the evidence and conduct observations. Because there are far too many indicators to keep in mind, the choice of indicators and the emphasis that they receive will inevitably vary greatly. Also, as schools identify and produce the evidence that they consider, there is some concern about the quality of the data, as identified by Nusche et al., (2012):

… quality of the data shows considerable variability.

This variability in the selection of indicators and the evidence that is used to investigate them can lead to questionable reliability, and more importantly, the validity of judgments relating to the ‘quality’ or ‘effectiveness’ of a school. Validity is:

… an integrated evaluative judgment of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness of interpretations and actions based on evidence from test scores or other assessments (Messick, 1990).

Local accountability has special standing in the New Zealand context, where the first audience is parents, whānau and community. This means that some of the issues associated with indicators as ‘measurement that has high reliability and validity’ are less pertinent.

A school developing its own criteria for self-evaluation is, of course, engaged in a different kind of exercise from researchers, and the purposes of the self-evaluation must be kept in mind. It is about needs, not just of pupils but of teachers too. It is about a range of things which supersede pupil achievement but are also preconditions for that. It is less concerned with norms and averages than with individuals and groups. What is important for an individual or a small group may be seen as a priority for the school although that group or person is, in a statistical sense, insignificant (MacBeath, Boyd, Rand & Bell, 1995).

Once again, it is important that ERO’s vision and purpose for school review, and its indicators, is very clear before decisions are made about how the framework should be revised.

Evaluative capacity

In this ‘knowledge age’ a great deal of energy is focused on data as knowledge and data as necessary for using knowledge well. The promise of data-based decision making is that better decisions and actions will follow. But moving from data to knowledge and better decisions is a complex process that involves acquisition, creation, representation, dissemination, validation, utilization and renewal of purposeful knowledge (Lin et al., 2006; Moteleb & Woodman, 2007).

Indicators and evidence are really only a small part of this. Earl & Katz (2006) maintain that using data is a complicated process of:

- standing back and deciding what you need to know and why

- collecting or locating the necessary data or evidence

- ensuring that the data are worth considering

- being aware of their limitations

- finding ways to link key data sources through organization and analysis

- thinking about what the results mean

- systematically considering an issue from a range of perspectives and using the data to either explain, support or challenge a point of view.

It is possible that data-based decision-making gets taken up as a simple (or simplistic) process, without sufficient attention to the complexity and the difficulty of coming to the kinds of deep understanding that leads to wise decisions. In this view, evaluative capacity is not about the data per se, but about the quality of the knowledge that emerges at the end. Good knowledge is founded on asking good questions, having good data, and engaging in good thinking (Earl & Seashore, 2013).

Good questions: All too often educational decisions get made using data that are available, rather than data that are appropriate. It is naive to imagine that disconnected indicators can provide a complete or nuanced view of the complexity of schools. Before indicators and evidence can be used to deepen understanding there needs to be clarity about the vexing issues that need decisions; it is these that provide a basis for formulating questions and hypotheses that can be investigated using data – through an iterative process of questions, investigation, interpretation, and new questions.

Good data: There is an explosion in the quantity and kinds of data being generated. However, there are many examples of unsophisticated data sets, narrow conceptions of what qualifies as data, and almost no capacity to use it well. It is critical that education very quickly becomes much more statistically capable to ensure that data about education is accurate, defensible and used appropriately. Data can be collected by outside agencies and provided to schools or it can be generated locally. Data can come in many forms (numbers, words, pictures, observations) as indicators of underlying ideas. Educators need to ask: ‘What kind of data do we need to help us make this decision?’ ‘What will give deeper insight and allow testing of hypotheses?’

Having good data means having the right data to examine important questions. Using good data means having the technical knowledge to determine the quality of the data and to analyse it in ways that capture the complexity of the issues. Data literacy is an important new capability for school personnel as they delve deeper into their structures and practices. Decisions based on bad data are likely to be bad decisions. Data are only symbolic representations of bigger ideas; they are only as good as their collection and the subsequent analysis and interpretation.

There is a complete science around data quality and analysis. For educators, it is important to know that the data they are considering come from defensible sources, are systematically collected, and are supported by other information. Data becomes useable information only when it is analysed, shaped and organized to reveal patterns and relationships. In the case of quantitative data, this means statistical analysis, directed by a set of guiding hypotheses or theories. In the case of qualitative data, the analysis can be founded in theory or via an inductive process in which the data is organized into themes. Whatever the process, it is the analysis is that takes the data beyond discrete items and follows the logic of the investigation. Using data requires facility with a range of analytical techniques that can sort and organize it in different ways so that it reveals its patterns.

Good thinking: The prime consideration in building good knowledge, not surprisingly, lies in the quality of the thinking. Data do not answer questions; rather, they provide additional information that may shed light on complex educational issues. Data analysis provides tools for the complex business of understanding issues better, considering nuance and context, and focusing and targeting work in productive ways. This human activity involves not only capturing and organizing ideas through data analysis, but also making sense of the patterns that reveal themselves and determining what they might mean for action (Earl and Katz, 2006). Data may enable measurement of educational concepts, but interpretation is where the real expertise comes in. What does the data mean? What does it add to the understanding? What else do we need to know? This is the heart of the matter.

This kind of thinking is not amenable to a generalized approach. It is set first by the questions that need answering and then by the policy context, the nature and availability of data, and the expertise of the participants. It is fundamentally an inquiry process that uses data as a starting point for focusing and challenging thinking. When educators engage in conversations about what evidence means they can interrupt the status quo and create a space for alternative views to emerge alongside their own as a prelude to decision-making.

Conclusion

New Zealand’s approach to indicators is dynamic and evolving. At this point in time ERO has some fundamental decisions to make to ensure that the current revision process results in a system that will prove a rigorous yet flexible guide to school review and data use.

Footnotes

1. For a more complete review of the history and current work in these areas see www.icsei.net and Townsend, T. (ed.) (2007) International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement. Springer.

2. Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment https://www.oecd.org/education/school/synergies-for-better-learning.htm

3. The details of the prompts and indicators can be found at http://www.ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Evaluation-Indicators-for-School-Reviews/PART-TWO-The-Evaluative- Questions-Prompts-and-Indicators

References

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Earl, L., & Katz, S. (2006). Leading in a data rich world. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Earl, L., & Seashore, K. (2013). Data Use: Where to from Here? In Schildkamp, K., Lai, M. & Earl, L. (eds.) Data-based decision making in education: Challenges and opportunities. Springer Publishing.

Coburn, C. (2003). Rethinking scale: moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change, Educational Researcher, 32 (6), 3-12.

Creemers, B.P.M., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). The dynamics of educational effectiveness: A contribution to policy, practice, and theory in contemporary schools. London: Routledge.

Educational Review Office (2011). Evaluation Indicators for School Reviews. Wellington: Author. Elmore, R. (2004). School reform from the inside out: policy, practice, and performance.

Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Education Press.

Gray, J., Hopkins, D., Reynolds, D., Wilcox, B., Farrel, S., & Jesson, D. (1999). Improving schools: Performance and potential. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hopkins, D. (2001). School improvement for real. London: Routledge Falmer.

Leithwood, K., Edge, K., & Jantzi, D. (1999). Educational cccountability: The state of the art. Gutersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers.

Lezotte, Lawrence W. (1991). Correlates of effective schools: The first and second generation. Okemos, MI: Effective Schools Products, Ltd.

Lin, Y., Wang, L., & Tserng, H.P. (2006). Enhancing knowledge exchange through web map-based knowledge management systems in construction: Lessons learned in Taiwan. Automation in Construction, 15, 693–705.

MacBeath, J., Boyd, B., Rand, J., & Bell, S. (1995). Schools speak for themselves. United Kingdom: National Union of Teachers.

Messick, S. (1990). Validity of test interpretation and use, Volume 11. Volume 90 of Educational Testing Service Princeton, NJ: ETS research report (Educational Testing Service).

Mortimore, P., Sammons, P., Stoll, L., Lewis, D., & Ecob, R. (1988). School matters: the junior years. Wells: Open Books.

Moteleb, A. A., & Woodman, M. (2007). Notions of knowledge management systems: A gap analysis. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 5 (1), 55 – 62. www.ejkm.com OECD (2013). Synergies for better learning: An international perspective on evaluation and assessment: A summary. Paris: OECD.

Mutch, C. (2013) Developing a conceptual framework for school review. In Kushner, S. & Lai, M. A developmental and negotiated approach to school self-evaluation. Advances in Program Evaluation. Volume 14. United Kingdom: Emerald.

Nusche, D., Laveault, D., MacBeath, J., & Santiago, P. (2012). OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education: New Zealand 2011. Paris, France: OECD.

Ontario Ministry of Education (2010). School effectiveness framework. Toronto: Ministry of Education.

Rutter, M., Maughan, B., Mortimore, P., & Ouston, J. (1979). Fifteen thousand hours: Secondary schools and their effects on children. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Scheerens, J., Ehren, M., Sleegers, P., & de Leeuw, R. (2012). OECD Review on evaluation and assessment frameworks for improving school outcomes: Country background report for the Netherlands. University of Twente, www.oecd.org/edu/evaluationpolicy

Shavelson, Richard J., McDonnell, L., & J. Oakes (1991). What are educational indicators and indicator systems? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 2(11).

Teddlie, C., & Reynolds, D. (2000). The international handbook of school effectiveness research. London: Falmer Press.

Timperley, H. (2013). The New Zealand educational context: Evaluation and self-review in a self- managing system. In Kushner, S. & Lai, M. (Eds.), A developmental and negotiated approach to school self-evaluation. Advances in Program Evaluation. Volume 14. United Kingdom: Emerald.

Stufflebeam, D. L. (1983). The CIPP model for program evaluation. In G. F. Madaus, M. Scriven, & D. L. Stufflebeam (Eds.), Evaluation models (pp. 117-141). Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff.

Whitty, G., Powers, S., & Halpin, D. (1998). Devolution and choice in education: the state, the school and the market. Buckingham: Open University Press.