Summary

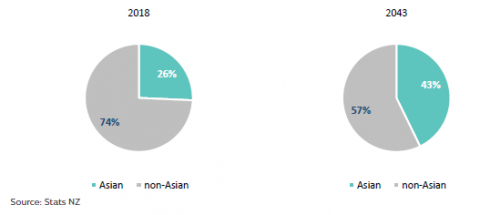

Aotearoa New Zealand is becoming more ethnically diverse, and this is changing quickly. It is fastest in urban areas, but diversity is increasing across the country. In the future, more of our learners will be from ethnic communities and speak a wider variety of languages. By 2043, it is expected that more than one in four learners in Aotearoa New Zealand will be from an ethnic community. In Auckland, it is expected that more than two in five learners will be Asian.

It is critical that education meets the needs of all our children. This report finds that many learners from ethnic communities are succeeding in education but encounter racism, isolation, and lack of cultural understanding.

We must achieve significant change if Aotearoa New Zealand is to be a great place to learn for children and young people from ethnic communities.

This is a draft for consultation – we are seeking your feedback

- You can make a submission through the following link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/DraftLTIBSubmission

- Questions are available in the following languages: English, Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Hindi, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, Spanish, Tagalog, Vietnamese

- You do not have to answer all questions.

The closing date for submissions is Tuesday 20 December 2022.

You can read a short summary of this report here: Education For All Our Children: Embracing Diverse Cultures - Summary of draft for consultation | Education Review Office (ero.govt.nz)

Whole article:

Education For All Our Children: Embracing Diverse Cultures - Draft for consultationAcknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the learners, parents and whānau, leaders, teachers, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights through interviews, group discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time, and for sharing your knowledge and experiences so openly and whole‑heartedly.

We also thank the key people from the Ministry for Ethnic Communities, the Ministry of Education, and the Human Rights Commission for their support in delivering this report, and those who participated in interviews.

We also thank the individuals and organisations who made submissions on the topic consultation we held in March 2022.

We want to give special acknowledgement to Multicultural New Zealand for distributing the surveys through their networks.

We want to acknowledge and thank the members of the Expert Advisory Group who shared their knowledge and wisdom in guiding this evaluation.

The members were:

- Dr Angel Chan, Senior Lecturer, School of Curriculum and Pedagogy, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland

- Sarah Denny, Hagley Community College

- Professor Stephen May, Te Puna Wānanga (School of Māori and Indigenous Education), Faculty of Education, University of Auckland

- Prem Singh, Multicultural New Zealand

- Nera Tautau, Human Rights Commission.

Executive summary

Aotearoa New Zealand is becoming more ethnically diverse, and this is changing quickly. It is fastest in urban areas, but diversity is increasing across the country. In the future, more of our learners will be from ethnic communities and speak a wider variety of languages. By 2043, it is expected that more than one in four learners in Aotearoa New Zealand will be from an ethnic community. In Auckland, it is expected that more than two in five learners will be Asian.

It is critical that education meets the needs of all our children. This report finds that many learners from ethnic communities are succeeding in education but encounter racism, isolation, and lack of cultural understanding.

We must achieve significant change if Aotearoa New Zealand is to be a great place to learn for children and young people from ethnic communities.

This report shares what we know about learners from ethnic communities’ experiences of education, and the implications for the future of Aotearoa New Zealand. This report looks at:

- Demographics: How has ethnic diversity changed in schools and how will it change going forward?

- Experiences and outcomes: What are the education experiences of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau?

- Practices and challenges: What are good practices and challenges in meeting the needs of learners from ethnic communities?

- Future: How can schools prepare for a more diverse future and how can they be supported?

What is ethnic diversity?

There are many forms of diversity including, among others, ethnic, cultural, language, identity, and religious diversity. For this project we focus on ethnic diversity and associated language, cultural, and religious diversity. Ethnicity is defined as the ethnic groups that people identify with or feel they belong to. Ethnic communities included in this report are African, Asian, Latin‑American, and Middle‑Eastern. The Ministry for Ethnic Communities defines ethnic communities as people who identify as African, Asian, Latin-American, Middle-Eastern, or Continental European. Due to the responses to our surveys, and the data available, we do not include Continental European learners’ experiences in this report.

What does ethnic diversity look like in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and how is this likely to change?

Aotearoa New Zealand is becoming more ethnically diverse, and this is changing quickly. It is fastest in urban areas, but diversity is increasing across the country. Learners will be from a wider range of ethnic communities. By 2043, it is expected just over one in four (26 percent) learners will identify as Asian and around one in 20 (3.6 percent) will identify as Middle‑Eastern, Latin‑American, or African (MELAA). In Auckland, more than two in five (43 percent) learners will identify as Asian.

What are the educational experiences of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau?

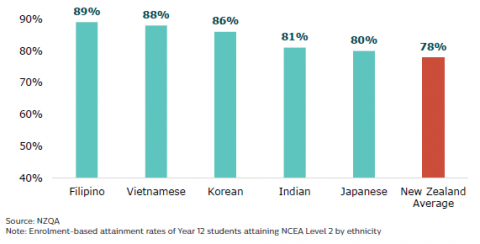

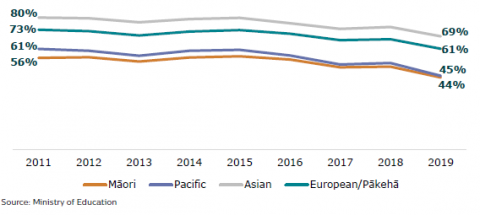

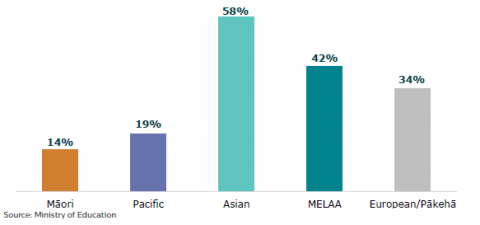

Many, but not all, learners from ethnic communities achieve well in education. Looking at NCEA Level 2 results, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean learners all achieve above the national average. However, there are significant differences across ethnic communities, and within all ethnic communities there are learners who are not achieving well.

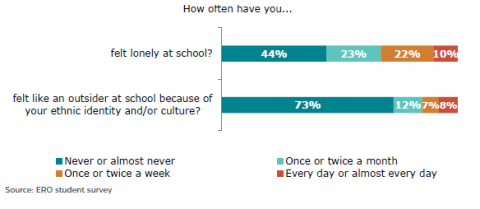

Learners from ethnic communities often do not feel they belong. Nearly one in five learners reported they frequently feel they do not belong and a third feel lonely at school. Nearly one in five also feel they have to hide their ethnic identity at school or feel excluded from activities because of their ethnic identity.

Learners from ethnic communities experience widespread racist bullying, which too often is not taken seriously by their school. One in five learners have experienced racist bullying in the last month, and over half have seen others being bullied because of their ethnicity. Both whānau and learners report that racist bullying needs to be better identified and addressed at school.

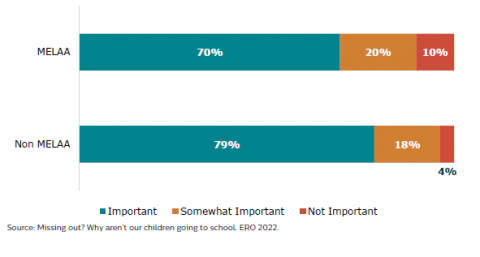

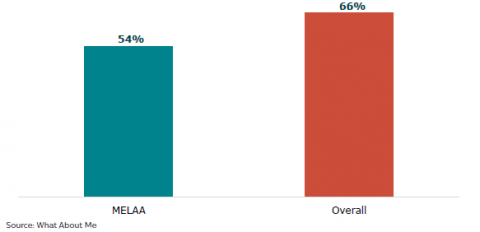

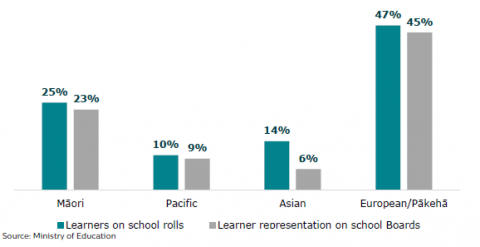

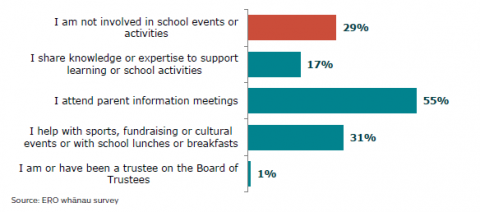

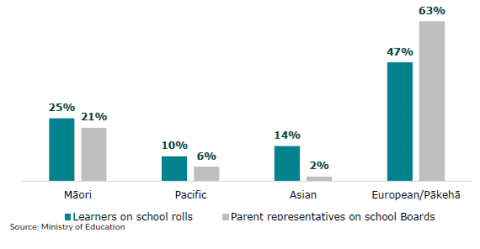

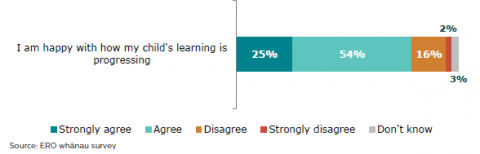

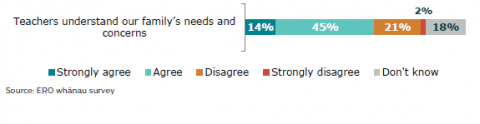

Whānau from ethnic communities face barriers to engaging with schools. They attend parent information sessions more than any other activity but find information about their children’s learning insufficient or confusing. They are significantly under-represented on School Boards.

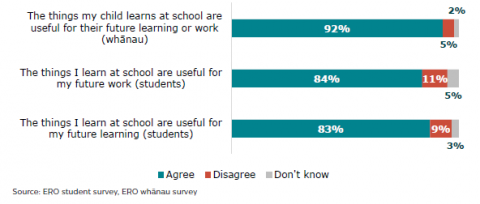

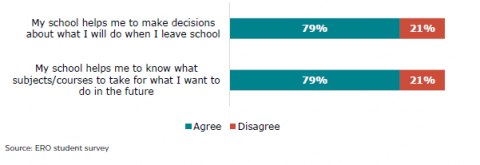

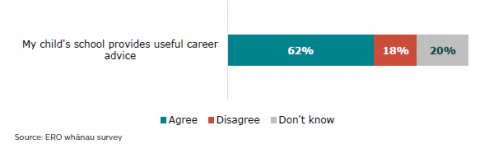

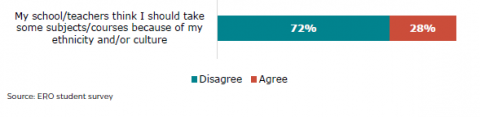

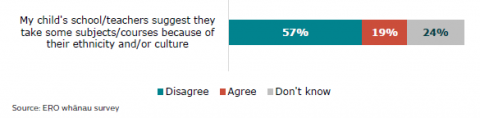

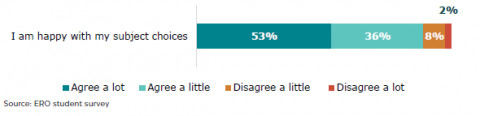

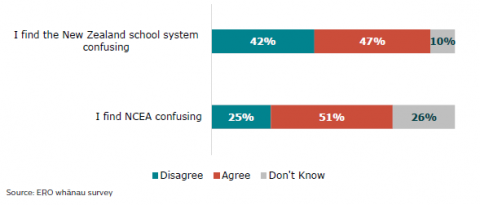

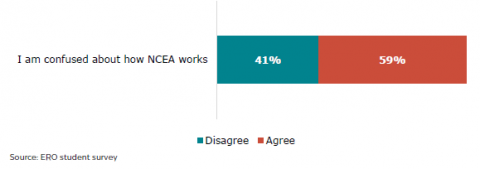

Many learners from ethnic communities go on to tertiary study, but pathways are confusing, and, for some, choices are unfairly constrained by teachers’ biases. More than one in four secondary learners report that teachers’ recommendations for their course selection are influenced by ethnicity, and only half of secondary learners are fully happy with their subject choices. Both learners and whānau find NCEA confusing.

How are schools meeting the needs of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau?

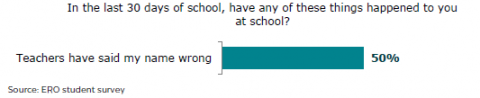

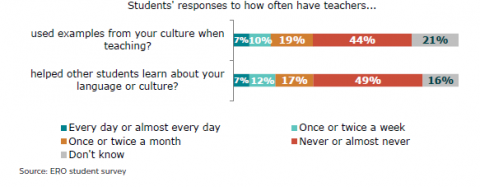

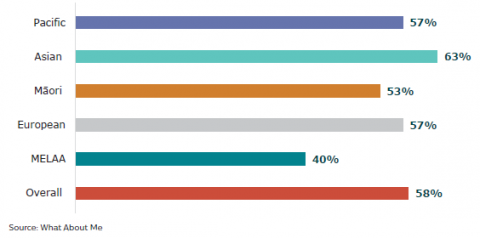

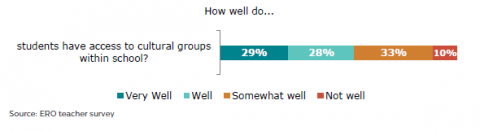

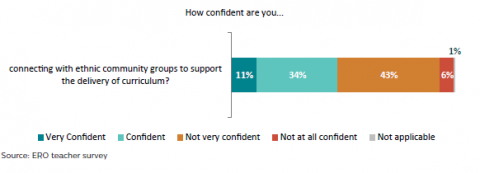

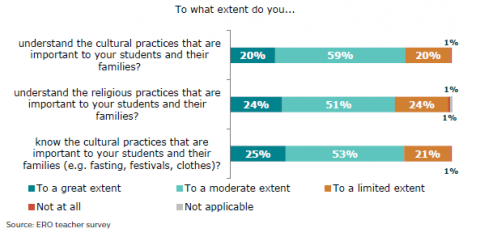

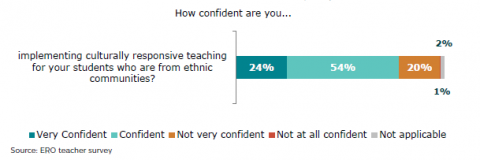

Teachers’ understanding of their learners, including their culture, is key to learners’ experiences at school, but this needs building. Whānau and learners are concerned about teachers’ lack of cultural knowledge and awareness. Teachers report having limited awareness of learners’ cultural and learning needs. More than half of teachers do not feel confident connecting with ethnic communities. Half of the learners from ethnic communities reported having their names mispronounced by their teacher.

Implications for education

Every school needs to be able to respond to increased diversity. Ethnic diversity is increasing across the country – not just in Auckland – and the largest changes are in the school-aged population. This increase in ethnic diversity is reflected in an increase in the diversity of cultural values, and the diversity of languages spoken. Every school needs to be able to meet the needs of learners from ethnic communities.

Every school will need to be able to tackle racism. In Aotearoa New Zealand there is more racism than we may be aware of. Too many learners from ethnic communities experience racist bullying and racial biases. We must do better.

We need to get better at delivering education for learners from ethnic communities. We need to understand more about what quality learning experiences and outcomes diverse ethnic communities want. This may include the types and locations of schools, and subjects taught. We must increase the cultural capability of the current teaching workforce, and develop a more culturally diverse teaching workforce for the future.

We need education to be good for learners and their whānau from ethnic communities to enable Aotearoa New Zealand to benefit from its increasing ethnic diversity. Learners and their whānau from ethnic communities have high aspirations for their learning and future pathways, and value maintaining their home languages. Supporting these aspirations and making Aotearoa New Zealand an attractive place to live for people of all ethnicities and cultures will help us strengthen our education system, workforce, culture, and relationships with other countries.

Key focus areas for the future

Many learners from ethnic communities are achieving in education but they have to overcome widespread racism, isolation, and lack of cultural understanding. We need to change. We will need action in five areas to ensure Aotearoa New Zealand is well-placed for the future.

- Strengthen understanding of ethnic communities and what they want from education. Ethnic communities have a wide variety of perspectives, values, and priorities for education. We need to strengthen our understanding of these within the education context.

- Develop our thinking on how we meet the needs of learners from ethnic communities in Aotearoa New Zealand. By deliberately exploring how we navigate differing religions and cultural values, and the intersection between ethnicity, language, culture, and identity in Aotearoa New Zealand’s education system, we can more effectively plan for the future.

- Recognise racism, understand the impacts, and tackle it more effectively. In some schools, teachers, learners, and others continue to allow ignorance, unconscious bias, and stereotyping to affect the way they engage with learners from ethnic communities and their whānau. This impacts on learners’ experiences of bullying, expectations of them, and options for their future study. Collectively, we need to end racism.

- Proactively build a teaching workforce that is better able to meet the needs of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau. To ensure learners from ethnic communities have teachers that understand them and meet their learning needs, we need to transform the teaching workforce.

- Harness the opportunities made available by the increasing ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand. Increasing ethnic diversity brings with it a wide range of opportunities that could strengthen not only Aotearoa New Zealand’s education system but our culture and economy. We need to realise these opportunities.

These are not quick actions; they will require sustained effort over coming decades. But the cost of not acting will be immense not only for the more than one in four learners from ethnic communities by 2043, but for New Zealand’s social cohesion, economy, and future.

Conclusion

Aotearoa New Zealand is becoming increasingly ethnically diverse. We must be a better place for learners from ethnic communities and their whānau. This will, in turn, put us in a stronger position economically and culturally as we become an even more attractive place for people from diverse ethnic communities to live, learn, work, and raise their families.

We are seeking your feedback

- You can make a submission through the following link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/DraftLTIBSubmission

- Questions are available in the following languages: English, Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Hindi, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, Spanish, Tagalog, Vietnamese.

- You do not have to answer all questions.

The closing date for submissions is Tuesday 20th December 2022.

About this report

Aotearoa New Zealand society is changing. The Education Review Office, in partnership with the Ministry for Ethnic Communities, wanted to understand the experiences of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau, and to explore the implications for the future of education.

This report describes what we found and the changes needed.

About the Education Review Office

The Education Review Office | Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga (ERO) is the Aotearoa New Zealand Government’s education evaluation agency. We work with early learning services, kōhanga reo, schools, and kura to help them and their learners flourish. We are interested in what is working well and what can improve.

Our focus is on equitable and excellent outcomes for all learners and our approach is driven by our whakataukī:

Ko te Tamaiti te Pūtake o te Kaupapa | The Child – the Heart of the Matter.

ERO is responsible for reviewing and reporting on education performance. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports learners’ outcomes – in this case on education for learners from ethnic communities in schools.

This is a Long-Term Insights Briefing

A Long-Term Insights Briefing (LTIB) helps identify and explore issues that matter for the future wellbeing of the people of Aotearoa New Zealand. They provide information about medium- and long-term trends, risks, and opportunities, and explore options on how best to respond.

LTIBs look to the past and present to think about the future – they are not Government policy. Chief Executives have a statutory duty to produce these briefings independent of Ministers. More information about LTIBs is on the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet website (see here).

This report is about making a difference

This report describes what we found about the increasing ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand, and the quality of education provision for learners from ethnic communities in schools. We also look at the implications of increasing ethnic diversity for the future.

The voices of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau are highlighted throughout this report. We describe their experiences of participation and learning, their outcomes, and how teaching practices impact on their learning and lives. Whānau’ refers to the extended family of these learners to acknowledge the importance of their close relationships and connections.

By providing a better understanding of diversity, this report will help schools and the education system to better prepare and plan for more diverse school environments.

Through understanding the experiences of these learners and showcasing good practice, this report will enable schools to better respond to the diverse ethnicities in their communities.

We partnered with others and drew on their expertise

For this evaluation, ERO partnered with the Ministry for Ethnic Communities.

The newly established Ministry for Ethnic Communities is the Government’s chief advisor on ethnic communities, ethnic diversity, and the inclusion of ethnic communities in wider society. They work with communities, other government agencies, and a range of organisations to help increase social cohesion and ensure Aotearoa New Zealand is a place where everyone feels welcome, valued, and empowered to be themselves.

We also worked closely with the Ministry of Education, and an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise, including people from ethnic communities, academics, practitioners, and agency officials.

Public consultation guided us to our questions

In March 2022, we published a LTIB topic consultation document1 and asked for submissions. The consultation document was available in seven languages (English, Te Reo Māori, Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Hindi, Japanese, Korean). Public consultation ran from 3 March to 1 April 2022. The consultation was communicated using ERO’s existing channels and through our partner networks. This included invitations to 169 organisations representing different ethnic, religious, or cultural groups, as well as peak bodies in education.

In May 2022, we published a LTIB: Summary of submissions and topic decision document.2 We received 21 submissions, 18 on behalf of organisations and three from individuals. The organisations comprised groups with a specific ethnic, cultural, or religious affiliation, as well as pan-ethnic, religious, or education groups. As a result of feedback, the title of the LTIB was changed to: Embracing diverse cultures: School practices. We have since changed it to the current title; Education for all our children: Embracing diverse ethnicities.

The word ‘embracing’ was chosen as it better aligns with the New Zealand Curriculum expectations for an inclusive and responsive curriculum.

A summary of submissions can be found here.

More details about our engagement approach are in Appendix 1.

What we looked at

- Demographics: How has ethnic diversity changed in schools and how will it change going forward?

- Experiences and outcomes: What are the education experiences of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau?

- Practices and challenges: What are good practices and challenges in meeting the needs of learners from ethnic communities?

- Future: How can schools prepare for a more diverse future and how can they be supported?

Where we looked

We focused on gathering the views of whānau and community leaders in ethnic communities in the context of English medium schools. To ensure we captured a range of experiences across a variety of learning contexts, we surveyed learners, whānau and communities, school leaders and teachers from a range of school types.

How we collected information

To understand how good education is for learners from ethnic communities we gathered information in multiple ways:

- surveys of whānau (1,250 responses), made available in 10 languages

- surveys of learners (558 responses)

- surveys of teachers (263 responses)

- site visits at eight schools

- seven community hui/focus groups

- interviews with 11 community leaders or submitters

- online focus groups with school leaders from eight schools.

In our surveys, not everyone who responded to our surveys answered every question. The numbers we report are the proportions of those who answered each particular question.

Further details of the methods we used are in Appendix 1.

What type of diversity?

There are many forms of diversity including, among others, ethnic, cultural, language, identity, religious. For this project we focus on ethnic diversity and associated language, cultural, and religious diversity. ERO has already looked at some other forms of diversity separately, for example our work on education for disabled learners.

Throughout the report, ethnicity is defined as the ethnic groups that people identify with or feel they belong to. Ethnicity is a measure of cultural affiliation. It is not a measure of race, ancestry, nationality, or citizenship. Ethnicity is self-perceived, and people can belong to more than one ethnic group.3

Ethnic groups include first and second generation New Zealanders and subsequent generations as well as migrants and refugees, and those born overseas.

Terms used in this report

In this report, when we use the term “learners from ethnic communities” we are referring to learners who identify as African, Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern.

Data from StatsNZ about the population – past, present and projected – is grouped by age group. We use children aged 5-19 when thinking about changes in the school‑age learner population and refer to this group as “learners”.

We use “whānau” in reference to the extended family of these learners to acknowledge the importance of their close relationships and connections.

Which ethnicities?

Our research on the outcomes and experiences of learners from ethnic communities includes anyone who identifies their ethnicity as:

- African

- Asian

- Latin-American

- Middle-Eastern.

While we asked about experiences and outcomes for learners from Continental Europe, the small number of responses and data available means we are not able to report on these learners in this draft report.

People from ethnic communities in Aotearoa New Zealand are an incredibly diverse group, representing over 200 ethnicities and speaking over 170 languages.4

Māori and Pacific learners in this report

Focusing on the ethnic communities listed sits alongside our first and primary commitment to Te Tīriti o Waitangi, and ensuring tamariki and rangatahi Māori are strongly supported to learn and thrive in their culture, language, and identity.

This research complements ERO’s wide range of research and resources on good culturally responsive practice for Māori learners.

We included the experiences of Māori and Pacific learners who belong to multiple ethnic communities. We also drew on learnings from successful culturally responsive practices for Māori learners and Pacific communities and how they may help support a broader range of diverse learners.

What are the expectations for education?

Aotearoa New Zealand has strong expectations for education to respond to the needs of all learners. The New Zealand Curriculum sets out expectations for an inclusive and responsive curriculum. Schools and teachers are expected to deliver a curriculum that:

- reflects our linguistically and culturally diverse nation

- affirms learners’ different cultural identities

- incorporates learners’ cultural contexts into teaching and learning programmes

- is responsive to diversity within ethnic groups

- helps learners understand and respect diverse viewpoints, values, customs, and languages.

The Education and Training Act 2020 states that it is desirable, as far as is reasonably practicable, that every Board should reflect the ethnic and socio-economic diversity of the student body of the school or special institution.5

The Teaching Council is Aotearoa New Zealand’s professional body for teachers. The Code of Professional Responsibility and Standards for the Teaching Profession (Our Code | Our Standards)6 sets out the expectations for the teaching profession, including expectations for how they work with learners from ethnic communities and their whānau. Through the Code, teachers are obligated to:

- work in the best interests of learners by respecting the diversity of the heritage, language, identity, and culture of all learners

- respect the vital role learners’ families and whānau play in supporting their children’s learning by respecting the diversity of the heritage, language, identity and culture of families and whānau.7

The Standards expect teachers to:

- understand and acknowledge the histories, heritages, languages, and cultures of partners to Te Tīriti o Waitangi

- critically examine how [their] own assumptions and beliefs, including cultural beliefs, impact on practice and the achievement of learners with different abilities and needs, backgrounds, genders, identities, languages, and cultures

- create an environment where learners can be confident in their identities, languages, cultures, and abilities

- design learning based on curriculum and pedagogical knowledge, assessment information and an understanding of each learner’s strengths, interests, needs, identities, languages, and cultures

- design and plan culturally responsive, evidence-based approaches that reflect the local community and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in New Zealand

- harness the rich capital that learners bring by providing culturally responsive and engaging contexts for learners.8

What does good look like?

Schools and societies around the world are becoming increasingly ethnically diverse. There are many different ways to think about what quality experiences and outcomes for learners from ethnic communities and their whānau look like.

We considered a variety of different frameworks when designing this work. In this report, we use the framework of the OECD.9 This framework sets out:

- Outcomes – for individuals, and equity and inclusion within the system.

- Outcomes – in society (for example labour market outcomes, or social outcomes)

We looked at four of their domains that influence the quality of those outcomes:

- Governing diversity, inclusion, and equity in education; including goals and expectations for teachers and schools.

- Developing capacity for managing diversity, inclusion, and equity in education; including awareness of diversity in education and teacher capability and capacity.

- Promoting school-level interventions to support diversity, inclusion and equity in education; including teaching practices, support for learners, and engagement with parents and communities.

- Monitoring and evaluating diversity, inclusion, and equity in education; including understanding progress.

The framework includes an additional domain on resourcing which is outside the scope of this project work. A diagram giving an overview of the framework is in Appendix 2.

Report structure

This report has five parts.

- Part 1 sets out how ethnic diversity is changing.

- Part 2 captures the educational experiences of learners from ethnic communities, including:

- learning and achievement

- cultural identity, belonging and inclusion, and wellbeing

- participation and engagement

- learning pathways and post-school destinations.

- Part 3 outlines how schools meet the needs of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau.

- Part 4 brings together the key findings from the evidence and their implications for the future.

- Part 5 sets out the next steps, including how to provide feedback on this draft report and when we expect to publish the final report.

This is a draft for consultation

At the end of each section, there is a box with some prompts for feedback. Think about your responses to these questions, and make a submission by Tuesday 20th December 2022.

Submitting your feedback

- Submit your feedback through the following link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/DraftLTIBSubmission

- Questions are available in the following languages: English, Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Hindi, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, Spanish, Tagalog, Vietnamese.

- You do not have to answer all questions.

The closing date for submissions is Tuesday 20 December 2022.

Part 1: How is ethnic diversity in schools changing?

Ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand is increasing, and the proportion of learners from ethnic communities in our schools is growing. To think about what we need to do to support these learners, we need to understand ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand now, and what it will look like in the future.

In this section, we set out how ethnic diversity has changed in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and how it will change in the future.

It is important to understand the diversity in our system so we can understand who is affected by different experiences, in what ways, and what outcomes they achieve. The OECD identified awareness of diversity in education at a system level as one of the main ways we can work to develop capacity for managing diversity, inclusion and equity in education.10

How we gathered information

To understand ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand schools and how it is changing, we used a variety of existing data. This included:

- census Population data

- Ministry of Education data

- StatsNZ data about projected ethnic diversity patterns

- data from international studies on education (studies we looked at include PISA, TIMMS, and PIRLS. These provide background knowledge on students’ learning to facilitate better education, specifically in terms of reading, mathematics, and science. They are global studies administered by the OECD).

This section describes:

- How diversity has changed in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- How diversity will change going forward.

What we found: an overview

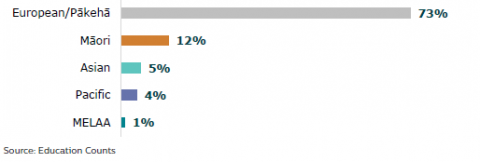

Ethnic diversity has increased. The ethnic diversity of Aotearoa New Zealand’s population has grown over the last two decades. Diversity has also increased within ethnic groups, and our school-age population has become more diverse. These changes have not been limited to a specific region – they have happened throughout the country. In 2018, 14 percent of learners (aged five to 19 years) were Asian and nearly 2 percent were Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African (MELAA). In Auckland, 26 percent were Asian and over two percent were MELAA.

Ethnic diversity will continue to increase. In the next two decades, the ethnic diversity of learners aged five to 19 years will continue to increase, with the largest growth expected to be in the numbers of Asian learners. By 2043, it is expected just over one in four (26 percent) learners will identify as Asian and around one in 20 (3.6 percent) will identify as MELAA. In Auckland, more than two in five (43 percent) learners are expected to identify as Asian.11

How has diversity changed in Aotearoa New Zealand?

This section looks at:

- the changing population

- the changing population of learners

- differences between schools.

1. The changing population

Ethnic diversity is rapidly increasing

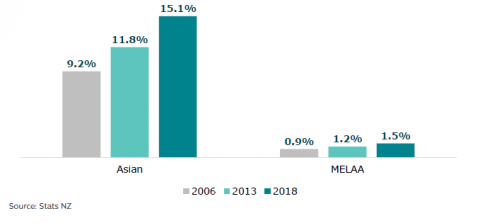

Aotearoa New Zealand’s ethnic diversity has grown quickly over the last two decades. For example, Census data from 2006 to 2018 shows Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Japanese, Sri Lankan, Cambodian, and MELAA groups have all grown as a proportion of the country’s total population. Between 2006 and 2018, the Asian population has increased from 9.2 percent to 15.1 percent, while the MELAA population has grown from 0.9 percent to 1.5 percent (see Figure 1).12

Figure 1: Ethnicities in Aotearoa New Zealand's population: 2006 - 201813

Figure one is a graph showing the population proportions of two ethnic groups (Asian and MELLA) of New Zealand’s total population, in 2006, 2013 and 2018. Asian population increased from 9.2% in 2006 to 11.8% in 2013 and then to 15.1% in 2018. MELLA population increased from 0.9% in 2006 to 1.2% in 2013, and to 1.5% in 2018.

Increasingly, people from ethnic communities are born in New Zealand

People from Asian and MELAA ethnic communities are increasingly born in Aotearoa New Zealand. In 2006, 20 percent of the Asian population was born in Aotearoa New Zealand. This increased to 23 percent by 2018. Similarly, 19 percent of the MELAA population was born in Aotearoa New Zealand in 2006, increasing to 23 percent by 2018.14

Ethnic communities are changing

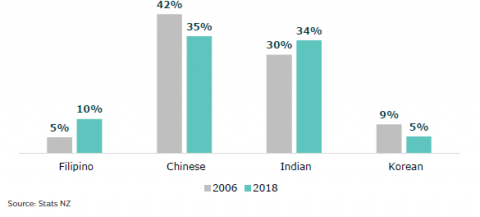

Diversity has also changed within these ethnic groups. For example, within the Asian ethnic group in Aotearoa New Zealand, the number of people identifying as Indian and Filipino increased rapidly between 2006 and 2018. The proportion of Indian people grew from 30 percent of the Asian population to 34 percent. The proportion of people identifying as Filipino increased from 5 percent to 10 percent of the Asian population (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of ethnicities within the Asian ethnic group: 2006-201815

Figure two is a graph showing the proportion of the population of different ethnicities (Filipino, Chinese, Indian and Korean) among the total Asian population in 2006 and 2018. The proportion of Filipino increased from 5% in 2006 to 10% in 2018. Chinese population decreased from 42% in 2006 to 35% in 2018. Indian population increased from 30% in 2006 to 34% in 2018. Korean population decreased from 9% in 2006 to 5% in 2018.

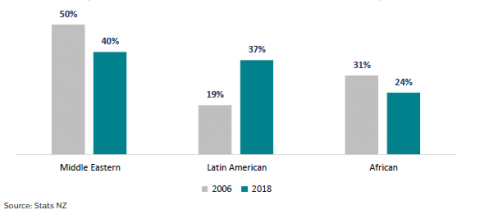

We can also see change within the MELAA group in Aotearoa New Zealand. Middle Eastern people were 40 percent of the MELAA population in 2018, decreasing from 50 percent in 2006. African people also decreased from 31 percent in 2006 to 24 percent in 2018. However, Latin American people increased from 19 to 37 percent of the MELAA group from 2006-2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of ethnicities within the MELAA ethnic group: 2006-201816

Figure three is a graph showing the proportion of the population of different ethnicities (Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African) among the total MELLA population in 2006 and 2018. The proportion of Middle Eastern decreased from 50% in 2006 to 40% in 2018. Latin American increased from 19% in 2006 to 37% in 2018. African population decreased from 31% in 2006 to 24% in 2018.

There has been rapid growth in the number of speakers of languages other than English

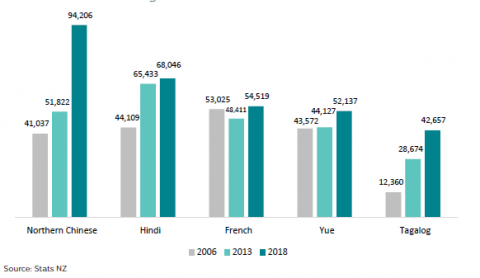

Since 2006, the number of people who are speakers of languages other than English in Aotearoa New Zealand has steadily increased. For example, the number of Northern Chinese speakers has more than doubled between 2006 and 2018, while Tagalog speakers have more than tripled. Figure 4 shows a selection of the five most common languages in Aotearoa New Zealand, and the increase in numbers of speakers of those languages over time.

Tagalog is a second language for the majority of people in the Philippines. Yue is spoken in Southern China. Hindi is spoken in parts of Northern, Central, Eastern and Western India.

Figure 4: Number of Aotearoa New Zealand residents who speak languages other than English: 2006-201817

Figure four is a graph showing the number of residents who speaks the following five most common non-English languages (Tagalog, Yue, French, Hindi and Northern Chinese) in 2006, 2013 and 2018.

The number of Tagalog speakers were 12,360 in 2006, 28,674 in 2013 and 42, 657 in 2018.

Yue speakers increased from 43, 572 in 2006 to 44, 127 in 2013 and 52, 137 in 2018.

The number of French speakers were 53,025, 48,411 and 54,519 in 2006, 2013 and 2018.

The numbers of Hindi speakers were 44,109, 65, 433 and 68,046 in 2006, 2013 and 2018. The number of Northern Chinese speakers were 41, 037, 51,822 and 94, 206 in 2006, 2013 and 2018.

2. The changing population of learners

Ethnic diversity is increasing in Aotearoa New Zealand schools.

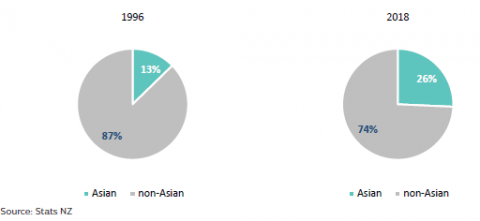

In 2018, 14 percent of learners were Asian, up from 6 percent in 1996. The percent who identified as MELAA is now 2 percent and has tripled since 1996. Change is happening across the country. In Auckland, the Asian population of learners has increased from 13 to 26 percent. In Southland, the proportion of Asian learners has grown from 1 to 6 percent (see Figures 5 and 6 - regional projections are not available for MELAA populations).

Figure 5: Proportion of learners in Auckland who identify as Asian: 199618 and 201819

Figure five is a graph showing the proportion of Asian learners’ population in Auckland in 1996 and 2018. 13% learners were Asians in Auckland in 1996, and the number went up to 26% in 2018.

Figure 6: Proportion of learners in Southland who identify as Asian: 199620 and 201821

Figure six is a graph showing the proportion of Asian learners’ population in Southland in 1996 and 2018. In 1996, 1 % learners in Southland were Asian, and 6% learners were Asian in 2018.

Increasingly, children from ethnic communities are born in New Zealand

The number of children from ethnic communities born in Aotearoa New Zealand is growing.

In 2006, 59 percent of zero to 14 year olds of Asian ethnicity were born in Aotearoa New Zealand. By 2018 this had increased to 72 percent, to a total of 103,635. The trend is similar for MELAA children. In 2006, 49 percent were born in Aotearoa New Zealand. By 2018 this had increased to 67 percent, to a total of 11,619.22

Migration patterns impact the numbers of children from ethnic communities born in Aotearoa New Zealand over time. Although we see a trend towards an increase from 2006-2018, the numbers of people from Asian and MELAA ethnic communities born in New Zealand could continue to increase or decline, depending on future migration patterns.

More learners speaking languages other than English

Increasing ethnic diversity is leading to an increase in the number of learners of languages other than English at home. For example, 30 percent of Year 5 Asian learners speak English at home, compared to 69 percent of all Year 5 learners.23

Increasingly, learners have multiple ethnicities

Many learners identify with more than one ethnic group. For example, around 133,800 children aged from five to 19 years old were identified as Asian in the 2018 Census. Within this group, about 28,185 (21 percent) were reported as identifying with more than one ethnic group. This has increased since 2006 when 16 percent of Asian youth identified as more than one ethnic group.24

In the MELAA population there is a greater rate of multiple ethnicities. In 2006, 24 percent of MELAA youth (aged 5-19 years) were identified with more than one ethnicity. In 2018, this had grown to 37 percent.25

3. Differences between schools

Some ethnicities are more likely to attend high decile schools

Changing diversity looks different for different schools. For example, ethnic distribution varies across school deciles. Low decile schools serve poorer communities, and high decile schools serve richer communities. In 2021, Indian, South-East Asian, and Middle Eastern learners were evenly spread across deciles nationally, but Chinese, Latin American, African, and Other Asian learners mostly attended high decile schools (see Figure 7).

Low decile refers to deciles 1, 2 and 3. Middle decile refers to deciles 4, 5, 6 and 7. High decile refers to deciles 8, 9 and 10.

Figure 7: Ethnicity spread across school decile groups: 2021

Figure seven is a graph showing the number of students in the following ethnic groups attending schools across the following three decile groups.

1693, 2682 and 2739 middle eastern learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

423, 1816 and 2381 Latin American learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

1260,4562 and 5014 African learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

1221, 8790 and 26315 Chinese learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

7946, 14615 and 12226 Indian learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

5391, 11794 and 9213 South east Asian learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

2047, 7283 and 11554 Other Asian learners were in low, mid and high decile schools.

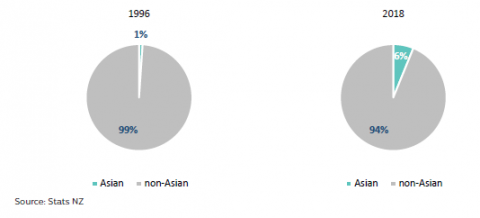

Learners from ethnic communities are more likely to be in urban schools

Most learners from ethnic communities go to schools located in urban areas. For example, 99 percent of Chinese and Indian learners go to schools in urban areas, compared to 92 percent in the average New Zealand population. South‑East Asian (3 percent), African (5 percent), and Latin American (6 percent) learners are more likely to go to schools in rural areas compared to Chinese (1 percent), Indian (1 percent), and Middle Eastern (1 percent) learners.

How will diversity change going forward?

This section shares:

- how the population will change

- how the population of learners will change.

We have used StatsNZ’s population projections. As the future is far from certain these projections include ranges. We have used the medium projection of these ranges. Appendix 3 has more detail on these projections.

1. How the population will change

By 2043, 24 percent of our population is expected to identify as Asian26 – this is likely to be 44 percent in Auckland.27

Aotearoa New Zealand’s population is expected to continue to become more ethnically diverse over the next two decades.

By 2043, we expect the Asian population to grow to 24 percent of our population, up from 15 percent in 2018.

By 2043, we expect the Asian population to grow to 44 percent of Auckland’s population, increasing from 28 percent in 2018.28 But this growth is not just in Auckland, for example, in the Southland region, the Asian population is expected to increase from 6 to 19 percent.29

The MELAA population of Aotearoa New Zealand will also increase. Between 2018 and 2043 we expect the MELAA ethnic community to increase from 1.5 to almost 3 percent of the population.30

2. How the population of learners will change

By 2043, 26 percent of learners are expected to identify as Asian, and 4 percent MELAA. In Auckland, 43 percent are expected to identify as Asian.

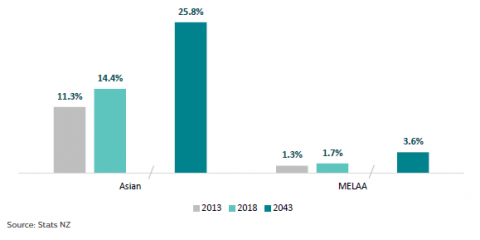

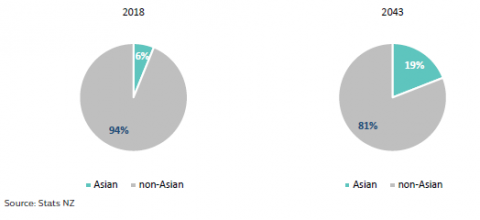

MELAA and Asian populations are expected to grow quickly in schools. The Asian learner population is projected to increase from 14 percent in 2018, to 26 percent by 2043. The population of MELAA learners is projected to more than double, from 1.7 to 3.6 percent (see Figure 8).31

Figure 8: Proportion of learners in Aotearoa New Zealand who identify as MELAA or Asian

Figure eight is a graph showing the proportion of learners who identify as MELAA or Asian in 2013, 2018 and 2043.

The proportion of Asian learners were 11.3% and 14.1% in 2013 and 2018. The figure will go up to 25.8% in 2043.

The proportion of MELAA learners were 1.3% and 1.7% in 2013 and 2018. The figure will go up to 3.6% in 2043.

The Asian population in schools is expected to increase across the country. The proportion of learners in Auckland who identify as Asian is expected to increase from 26 percent in 2018, to 43 percent by 2043 (see Figure 9). We will also see this growth regionally:

- Waikato, from 9 percent in 2018 to 21 percent by 2043

- Bay of Plenty, from 7 percent in 2018 to 19 percent by 2043

- Wellington, from 13 percent in 2018 to 28 percent by 2043

- Nelson, from 9 percent in 2018 to 24 percent by 2043

- Canterbury, from 11 percent in 2018 to 24 percent by 2043

- Southland, from 6 percent in 2018 to 19 percent by 2043 (see Figure 10).

Figure 9: Proportion of learners in Auckland who identify as Asian: 201832 and 204333

Figure 9 is a graph showing the proportion of learners who identified themselves as Asian in Auckland in 2018 and are projected to identify themselves as Asian in Auckland in 2043. 26% learners identified themselves as Asian in 2018 and 43% learners are projected to identify themselves as Asian in 2043.

Figure 10: Proportion of learners in Southland who identify as Asian: 201834 and 204335

Figure 10 is a graph showing the proportion of learners who identified themselves as Asian in Southland in 2018 and are projected to identify themselves as Asian in Auckland in 2043. 6% learners identified themselves as Asian in 2018 and 19% learners are projected to identify themselves as Asian in 2043.

Changes to individual school rolls

Changes at a regional level will affect the diversity of individual school rolls in different ways. Some schools will likely see a large increase in the numbers of learners from ethnic communities. For some schools, the increase may be small numbers from a wider range of ethnicities. For others, the increase may be from one or two ethnic communities. This may look different for neighbouring schools.

More information about these StatsNZ projections can be found in Appendix 3.

Conclusion

Ethnic diversity in Aotearoa New Zealand has increased and is expected to keep increasing. The number of learners from ethnic communities is increasing and by 2043, more than one in four learners will identify as Asian, and around one in 20 will identify as MELAA. They will increasingly speak languages other than English. Increased ethnic diversity will occur in all regions in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Feedback prompts

- How well do you relate to the findings in this section?

- What sits well with you?

- What is surprising?

- What is missing from this story?

- What are the implications?

Part 2: What are the educational experiences of learners from ethnic communities and their whānau?

Education is critical for all children and young people’s futures. Like other learners, learners from ethnic communities and their whānau want a variety of experiences and outcomes from their education so they can make friends, develop skills for life, and find pathways to careers.

This section describes their experiences in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and their transition from schooling to further education or the workforce. It finds that, although learners from ethnic communities have strong cultural identities and perform well at school, they face discrimination and racism that damages their sense of belonging, wellbeing, and access to future pathways.

How we gathered information

To understand the educational experiences and outcomes of learners from ethnic communities, we asked them and their whānau about their experiences at school. In both an online survey and through focus groups, we asked questions about their:

- learning and achievement

- cultural identity, belonging and inclusion, and wellbeing

- participation and engagement

- destinations and pathways.

More detail about the survey and focus groups can be found in Appendix 1.

We also looked at:

- data on learning, progress, and achievement for learners from ethnic communities

- data about attendance, participation, and engagement

- data about what learners from ethnic communities do when they leave school

- Ministry of Social Development’s What About Me? survey (2021).

This section describes

The OECD framework breaks outcomes into four areas:

- Individual wellbeing

- Equity and inclusion within the education system

- Individual outcomes

- Cohesion and inclusion in society

This section focuses on:

- learning and achievement – learners’ academic outcomes

- cultural identity, belonging and inclusion, and wellbeing – their psychological and social outcomes

- participation and engagement – learners’ inclusion in the education system

- destinations and learning pathways – their potential for labour market outcomes.

Across all these areas, we looked at where there is inequity based on learners’ and their whānau ethnicity.

What we found: an overview

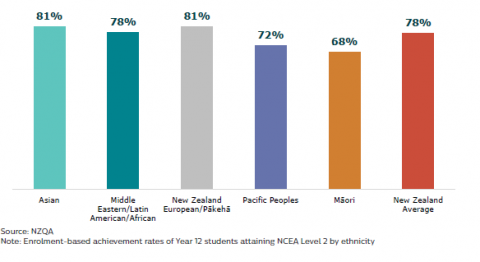

Many, but not all, learners from ethnic communities achieve well in education. Looking at NCEA Level 2 results, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean learners all achieve above the national average. However, there are significant differences across ethnic communities, and within all ethnic communities there are learners who are not achieving well.

Learners from ethnic communities often do not feel they belong. Nearly one in five learners reported they frequently feel they do not belong and a third feel lonely at school. Nearly one in five also feel they have to hide their ethnic identity at school or feel excluded from activities because of their ethnic identity.

Learners from ethnic communities experience widespread racist bullying, which too often is not taken seriously by their school. One in five learners have experienced racist bullying in the last month, and over half have seen others being bullied because of their ethnicity. Both whānau and learners report that racist bullying needs to be better identified and addressed at school.

Whānau from ethnic communities face barriers to engaging with schools. They attend parent information meetings more than any other activity but find information about their children’s learning insufficient or confusing. They are significantly under-represented on School Boards.

Many learners from ethnic communities go on to tertiary study, but pathways are confusing, and, for some, choices are unfairly constrained by teachers’ biases. More than one in four secondary learners report that teachers’ recommendations for their course selection are influenced by ethnicity and only half of secondary learners are fully happy with their subject choices. Many learners and whānau find NCEA confusing. NCEA is the National Certificate of Educational Achievement. For more information on NCEA, and how students achieve this, please visit National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) » NZQA

1. Learning and achievement

Learning and achievement in Aotearoa New Zealand schools is measured and reported in many ways. In primary schools, teachers and leaders choose how to measure and report learners’ progress and achievement. This information is not collected at a national level.

In secondary schools, learners can show their learning and achievement through the national qualification – NCEA. NCEA is offered at Levels 1, 2 and 3, which broadly line up with learners in Years 11, 12 and 13. Learners’ achievement is graded as either Not Achieved, Achieved, Achieved with Merit or Achieved with Excellence. They can choose credits and courses that suit them and their desired educational pathway. Learners may also gain University Entrance, which demonstrates they have the knowledge and skills required to enrol in first year studies at university.

In this section different ethnic groups (e.g. Asian, MELAA etc.) are examined alongside the overall New Zealand results. Learners from Ethnic Communities are included in the New Zealand results and therefore while the New Zealand results provide a point of reference, a direct comparison should not be made. An overview of NCEA overview can be found at https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/understanding-ncea/how-ncea-works/.

We can also understand Aotearoa New Zealand secondary learners’ achievement through international measures. In this report we use learners’ achievement in PISA, which measures 15 year olds’ achievement.

In this section we set out:

- Areas that are stronger:

- Higher NCEA achievement for most

- Higher endorsements

- Higher University Entrance

- Better achievement on international measures, particularly for Chinese learners

- Possible areas of concern:

- Lower NCEA achievement for some

- Greater gender gaps for Indian, African, and Middle Eastern learners

- Not being challenged at school

Areas that are stronger

Higher NCEA achievement for most

Learners from ethnic communities achieve well compared to others. Eighty one percent of Asian Year 12 learners achieve NCEA Level 2 compared with the New Zealand average at 78 percent. MELAA learners achieve at an equal rate to New Zealand learners overall, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: NCEA Level 2 attainment, by ethnicity: 2021

Figure 11 is a graph showing the Cumulative NCEA level 2 attainment rates for learners from the following ethnic groups in 2021. The attainment rates for Asian and New Zealand European was the highest at 81%, while the attainment rate for MELAA was 78%. The rate for Pacific peoples and Māori were 72% and 68% respectively. New Zealand average attainment rate was 78%.

Within the Asian group, we can see many ethnicities achieve more than the Aotearoa New Zealand average (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: NCEA Level 2 attainment, by Asian ethnicities (selected): 2021

Figure 12 is a graph showing the Cumulative NCEA level 2 attainment rates for learners from the following selected Asian ethnic groups in 2021. Filipino had the highest attainment rate at 89%. Vietnamese and Korean’s attainment rate were 88% and 86%. Indian’s attainment rate was 81%, while Japanese’s attainment rate was 80%. New Zealand average attainment rate was 78%.

Higher endorsements

Learners from ethnic communities achieve Merit and Excellence endorsements at a high

rate – 58 percent of Asian learners and 43 percent of MELAA learners achieve these endorsements at Level 2 compared to 42 percent of Aotearoa New Zealand learners as a whole (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: NCEA Level 2 Merit and Excellence endorsements, by ethnicity: 2021

Figure 13 is a graph showing Level 2 Merit and Excellence endorsement rates for learners from the following ethnic groups in 2021.

Asian had the highest Merit endorsement rate at 29%, and it had the highest Excellence endorsement rate at 29%.

MELAA’s Merit endorsement rate was 26% and its Excellence rate was 17%.

New Zealand European’s Merit endorsement rate was 25% and its Excellence endorsement rate was 19%.

The Merit endorsement rate for Maori was 16% and the excellent endorsement rate for Maori was 8%.

The Merit endorsement rate for Pacific people was 18% and the excellent endorsement rate was 7%.

New Zealand Average Merit endorsement rate was 24% and the average excellence endorsement rate was 18%.

Higher University Entrance

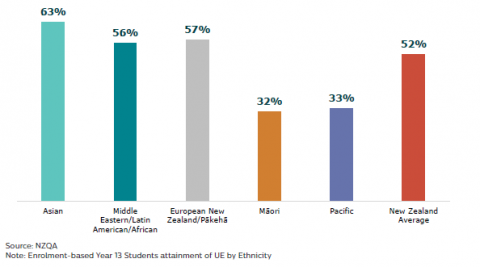

Many learners from ethnic communities are well-placed to attend university. Figure 14 below shows that 63 percent of Asian learners and 56 percent of MELAA learners achieve University Entrance compared with the New Zealand average at 52 percent.

Figure 14: University Entrance attainment, by ethnicity: 2021

Figure 14 is a graph showing University Entrance (UE) attainment rates for learners from the following ethnic groups in 2021.

Asian had the highest UE attainment rate at 63%, this is followed by European New Zealanders at 57%. The rate for MELLA was 56%, and the rates for Maori and Pacific people were 32% and 33% respectively.

The New Zealand average rate was 52%.

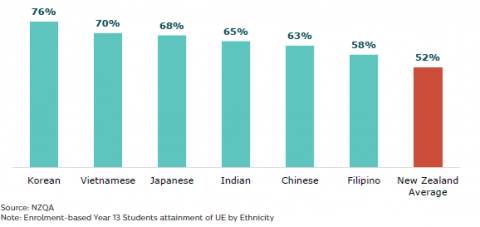

Within the Asian group, many ethnicities achieve University Entrance at a higher rate than the national average, as seen in Figure 15 below, with Koreans achieving at the highest rate (76 percent).

Figure 15: University Entrance attainment, by Asian ethnicities (selected): 2021

Figure 15 is a graph showing University Entrance (UE) attainment rates for learners from the following Asian ethnic groups in 2021. Koran had the highest UE attainment rate at 76%. This was followed by Vietnamese’s UE attainment rate at 70%.

The rates for Japanese, Indian and Chinese were all 68%, 65% and 63% respectively. The rate for Filipino were 58%. The New Zealand average rate was 52%.

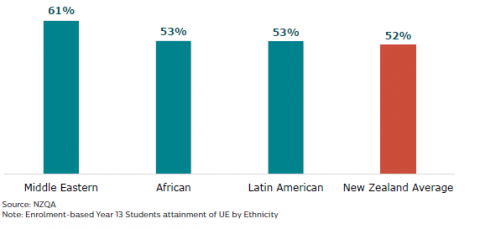

Middle Eastern, African and Latin American learners also achieve University Entrance above the New Zealand average (see Figure 16).

Figure 16: University Entrance attainment, by MELAA ethnicities: 2021

Figure 16 is a graph showing University Entrance (UE) attainment rates for learners from the following MELLA ethnic groups in 2021. Middle Eastern learners had the highest UE attainment rate at 61%. The UE attainment rates for Africans and Latin Americans were both 53%. The New Zealand average rate was 52%.

Better achievement on international measures, particularly for Chinese learners

Asian learners also achieve well on international measures. This is largely driven by Chinese learners’ achievement, where a large proportion of Chinese learners achieve at the highest levels (see Figure 17). Achievement on PISA for MELAA learners was not able to be reported due to small numbers. In this section different ethnic groups are examined alongside the overall New Zealand results. Learners from ethnic communities are included in the New Zealand results and therefore while the New Zealand results provide a point of reference, a direct comparison should not be made.

Figure 17: PISA Mathematics achievement of Asian learners, by sub-ethnicity: 2018

Figure 17 is a graph showing the PISA Mathematics achievement of Asian learners from different sub-ethnic groups.

22% New Zealanders achieved below level 2, 23% new Zealanders achieved level 2.

25% new Zealanders achieved level 3.

19% new Zealanders achieved level 4.

12% new Zealanders achieved level 5 or above.

11% Chinese achieved below level 2.

12% Chinese achieved level 2.

19% Chinese achieved level 3.

22% Chinese achieved level 4.

36% Chinese achieved level 5.

15% Filipino achieved below level 2.

23% Filipino achieved level 2.

29% Filipino achieved level 3.

22% Filipino achieved level 4.

9% Filipino achieved level 5.

21% Indian achieved below level 2.

22% Indian achieved level 2.

27% Indian achieved level 3.

20% Indian achieved level 4.

10% Indian achieved level 5.

Possible areas of concern

High achievement is not universal across learners. Within all ethnic groups, there are learners who are not achieving as well overall, or across the breadth of the curriculum.

Lower NCEA achievement for some

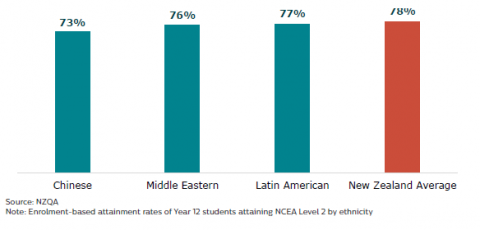

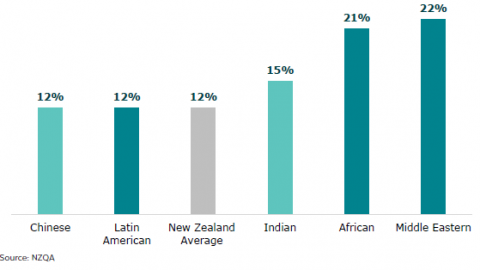

Not all learners from ethnic communities achieve well at NCEA 2. Chinese, Middle Eastern, and Latin American learners achieve slightly lower than the Aotearoa New Zealand average (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: NCEA Level 2 attainment by Chinese, Middle Eastern and Latin American: 2021

Figure 18 is a graph showing the NCEA Level 2 attainment rates of Chinese, Middle Eastern and Latin American learners in 2021.

The rate for Chinese learners was 73%.

The rate for Middle eastern learners was 76%.

The rate for Latin American learners was 77%.

The New Zealand average rate was 78%.

The picture for NCEA 2 achievement is a complex one as, although Chinese and Middle Eastern learners achieve below the New Zealand average for NCEA 2, they are more likely than the

New Zealand average to achieve University Entrance.

Greater gender gap for Indian, African, and Middle Eastern

For Indian, African, and Middle Eastern learners, the percentage point gap between male and female achievement of University Entrance is larger than the New Zealand average, as shown in Figure 19. For Chinese and Latin American learners, the gap between male and female achievement is similar to the New Zealand average but is still concerning.

Achieving University Entrance is a pre-requisite for many future destinations and pathways, so large gaps between male and female learners are concerning.

Figure 19: Achievement gap between male (lower achievement) and female (higher achievement) learners by ethnicity for University Entrance (selected): 2021

Figure 19 is a graph showing the achievement gap between male (with lower achievement) and female (with higher achievement) learners by ethnicity for University Entrance in 2021.

The gap between Chinese male and female learners was 12%.

The gap between Latin American male and female learners was 12%.

The average gap between New Zealand male and female learners was 12%.

The gap between Indian male and female learners was 15%.

The gap between African male and female learners was 21%.

The gap between Middle Eastern male and female learners was 22%.

Not being challenged at school

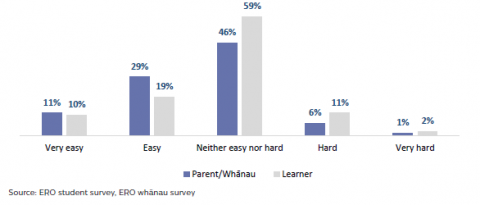

It is important that learning is at the right level to ensure learners progress. Forty percent of whānau from ethnic communities think their child’s schoolwork is easy or very easy, and 29 percent of learners from ethnic communities think this (see Figure 20).

Figure 20: Parent/whānau and learner agreement their schoolwork is at the right level of difficulty

Figure 20 is a graph showing how learners and parents from ethnic groups feel about the level of difficulty of their schoolwork.

11% parents from ethnic groups feel the schoolwork is very easy, and 29% parents feel the schoolwork is easy. 46% parents feel the schoolwork is neither easy nor hard. 6% parents feel the schoolwork is hard, and 1% parents feel the schoolwork is very hard.

10% learners from ethnic groups feel the schoolwork is very easy and 19% learners feel the schoolwork is easy.

59% learners feel the schoolwork is neither easy nor hard.

11% learners feel the schoolwork is hard and 2% learners feel the schoolwork is very hard.

Learners and whānau from ethnic communities lack information about how well they are learning and progressing. Over a third (36 percent) of learners are rarely or almost never told how well they are doing or what they are good at (see Figure 21).

School reports are very complicated. Migrant parents need extra help understanding them.

– Parent

This may contribute to concerns about their child’s level of academic achievement or challenge at school. Whānau from ethnic communities are particularly concerned when their child is not achieving, and teachers have not communicated this to them.

Figure 21: How frequently learners are told how well they are doing and what they are good at

Figure 21 is a graph showing how often learners from ethnic communities identified that in the last 30 days, their teachers told them what they are good at, and how often learners from ethnic communities identified that in the last 30 days, their teacher told them how well their learning is going?

9% learners identified their teachers never or almost never told them how good they were good at in the last 30 days.

27% learners identified their teachers told them how good they were good at once or twice a month in the last 30 days.

35% learners identified their teachers told them how good they were good at once or twice a week in the last 30 days.

18% learners identified their teachers told them how good they were good at every day or almost every day in the last 30 days.

10% learners identified they don’t know about it.

8% learners identified their teachers never or almost never told them how well their learning is going in the last 30 days.

28% learners identified their teachers told them how well their learning is going once or twice a month in the last 30 days.

38% learners identified their teachers told them how well their learning is going once or twice a week in the last 30 days.

20% learners identified their teachers told them how well their learning is going every day or almost every day in the last 30 days.

7% learners identified they don’t know about it.

2. Cultural identity, belonging and inclusion, and wellbeing

Maintaining family traditions and cultural heritage, cultural values and religious beliefs are more important for learners from ethnic communities compared with their European peers.36

To understand how well learners from ethnic communities are supported in their cultural identity, belonging and inclusion, and wellbeing, we asked them and their whānau about their experiences of school. We also looked at data from other sources to get a deeper understanding of the experiences of these learners.

In this section we set out:

- Areas that are stronger:

- Positive cultural identity

- Celebrating and respecting cultures

- Possible areas of concern:

- Widespread racism

- Not being accepted and not belonging

- … Particularly for MELAA

- Lack of cultural understanding

- Mismatch of values and practices

- Lack of recognition and support

- Poor wellbeing for MELAA

Areas that are stronger

Many learners and their whānau from ethnic communities have strong cultural identities and often feel included by their school communities.

Positive cultural identity

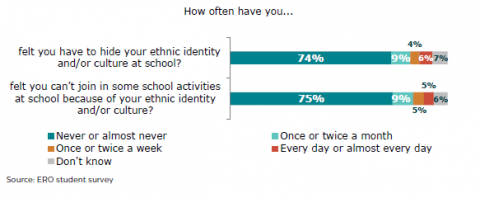

Many learners and whānau report positive feelings about their ethnic identity or culture at school. Almost four out of five whānau feel their child is proud of their ethnic identity or culture, whilst 64 percent of learners reported feeling proud at least once or twice a week. Most (74 percent) learners never or mostly never feel they have to hide their ethnic identity or culture at school, or that this aspect of their identity is a barrier to joining in some school activities (75 percent) (see Figure 22).

Figure 22: How often learners have to hide their ethnicity, or ethnicity is a barrier to participation

Figure 22 is a graph showing how often learners felt they have to hide their ethnic identity and, or culture at school, and how often learners felt they cannot join in some school activities at school because of their ethnic identity and, or culture?

74% learners identified they never or almost never felt they have to hide their ethnic identity and, or culture at school.

9% learners identified they have to hide their ethnic identity and, or culture at school once or twice a month.

4% learners identified they have to hide their ethnic identity and, or culture at school once or twice a week.

6% learners identified they have to hide their ethnic identity and, or culture at school every day or almost every day.

7% learners identified they don’t know.

75% learners identified they never or almost never felt they cannot join in some school activities at school because of their ethnic identity and, or culture.

9% learners identified they felt they cannot join in some school activities at school because of their ethnic identity and, or culture once or twice a month.

5% learners identified they felt they cannot join in some school activities at school because of their ethnic identity and, or culture once or twice a week.

5% learners identified they felt they cannot join in some school activities at school every day or almost every day.

6% identified they don’t know.

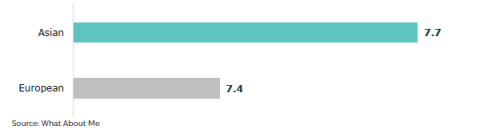

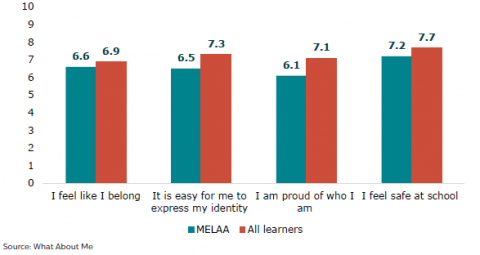

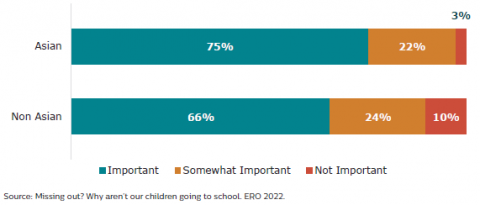

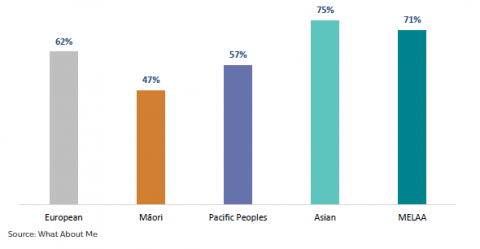

The What About Me? Survey results show that Asian learners feel more strongly than European learners that their identity and values are considered (see Figure 23).

Figure 23: How strongly ethnicities feel their identity and values are considered by teachers (scored 0-10/disagree to agree)

Figure 23 is a graph showing the mean scores of agreement level for learners in the following ethnic groups (Asian and European) feel their identity and values are considered by teachers.

The mean score of Asians was 7.7 out of 10.

The mean score of Europeans was 7.4 out of 10.

In focus groups, learners told us their sense of cultural identity was supported when:

- their cultural identity is visible in the environment and included in school practices,

they get to participate in cultural events and activities - they can speak or learn their first language and heritage.

It’s easy to be myself here.

– Learner

Celebrating and respecting cultures

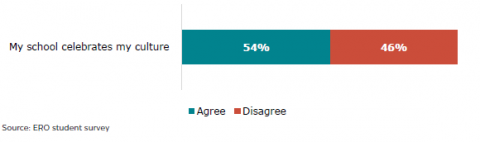

In our survey, the majority (54 percent) of learners agreed their school celebrates their culture (see Figure 24).

Figure 24: Schools celebrate culture – learner responses

Figure 24 is a graph showing the responses of learners from ethnic groups regarding to their school celebrating their culture.

54% learners agreed their school celebrated their culture while 46% disagreed with this

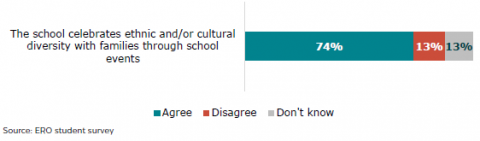

Whānau were more positive, with nearly three quarters saying their child’s school celebrates their culture (see Figure 25).

Figure 25: Schools celebrate culture – parent/whānau responses

Figure 25 is a graph showing the responses of whānau or parents from ethnic groups regarding to ‘The school celebrates ethnic and/ or cultural diversity with families through school events.’

74% whānau agreed their school celebrates ethnic and, or cultural diversity with families through school events. 13% whānau disagreed with this, and 13% whānau don’t know.

Whānau and learners are appreciative of these efforts by the school. Such cultural events acknowledge and recognize their culture which makes them feel valued and welcomed.

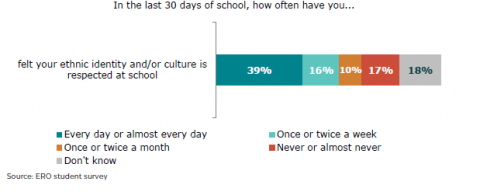

Most whānau (74 percent) also reported their child’s ethnic identity is often or always respected, and 55 percent of learners feel this way at least once or twice a week. Seventy-six percent of learners also told us their teachers know about cultural practices that are important to them.

The What About Me? survey asked about how fairly learners are treated by their teachers, and results were generally positive. Asian learners agreed most strongly (7.9/10) that they are treated fairly, compared to their European peers at 7.4/10. This was supported by our survey which found 80 percent of learners did not think they were treated unfairly.

Whānau also feel positive about their cultural identity when it comes to engaging with their child’s school – more than eight out of 10 said their identity is not a barrier to joining in cultural activities, or a factor in how fairly they are treated by the school (see Figure 26).

Figure 26: Parents/whānau agreement they cannot join in with school activities, or have been treated unfairly because of their ethnic identity and/or culture

Figure 26 is a graph showing whether whānau from ethnic groups agreed with the two statements ‘I have been treated unfairly at my child’s school because of my ethnic identity or culture.’ and ‘I feel I can’t join in school activities because of my ethnic identity and/ or culture.’

84% whānau disagreed with ‘I have been treated unfairly at my child’s school because of my ethnic identity or culture.’ 11% agreed with this and 5% don’t know.

89% whānau disagreed with ‘I feel I can’t join in school activities because of my ethnic identity and/ or culture.’ 8% agreed with this and 3% don’t know.

In our focus groups and interviews, whānau told us they appreciated when:

- schools have a family-like atmosphere

- schools worked to make community networks strong

- school staff are approachable

- a diversity of cultures is visible at their child’s school.

In our community hui, whānau described inclusive practices in their school which included food and religious practices. Some schools were also more flexible with uniforms to accommodate the needs of different ethnic communities. Members of the community found that some schools took a strength-based approach to diversity.

They recognise ethnic diversity. And it helps children live in school without being uncomfortable.

– Parent of a Year 13 learner

Possible areas of concern

Sadly, learners and their whānau report too many examples where their ethnicity or culture is not accepted or respected and their sense of belonging is negatively affected. Many of these reflect widespread instances of racism which have measurable impacts on the wellbeing of learners and their whānau.37

Widespread racism

International and Aotearoa New Zealand research into the impacts of racism on children highlight the wide range of impacts racism can have. Racism negatively affects children and young people’s:

- academic achievement, and contributes to the achievement gap between different ethnic groups38

- physical wellbeing, including increased likelihood of illness and impaired cognitive development39

- health-related behaviours, such as smoking and binge drinking40

- psychological wellbeing, increasing experiences of anxiety, depression, distress, and low resilience41

- quality of life, reducing levels of happiness, self-esteem, and self-worth.42

These impacts occur both when children experience racism themselves, or witness it occurring to others, such as their peers and/or whānau (known as vicarious racism). Because the harms associated with racism are so impactful it is incredibly important incidents are taken seriously as racism is often under-reported.43

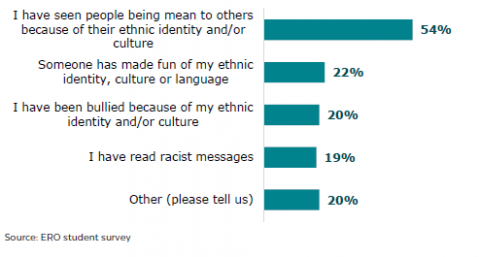

Levels of racism and racist bullying are unacceptably high and are of key concerns for families and learners in our survey (see Figure 27). Learners reported high levels of racist bullying within the last month:

- more than half (54 percent) of learners reported seeing someone being mean to others because of their ethnic identity and/or culture

- one in five (22 percent) have experienced someone making fun of their ethnicity, culture or language

- one in five (20 percent) have been bullied because of their ethnic identity and/or culture

- one in five (19 percent) have read racist messages.

Figure 27: Learners’ experiences of racist bullying and racism

Figure 27 is a graph showing the percentage of learners who reported the following things happened to them at school in the last 30 days of school.

54% reported ‘I have seen people being mean to others because of their ethnic identity and or culture.’

22% reported ‘someone has made fun of my ethnic identity, culture or language.

20% reported ‘I have been bullied because of my ethnic identity and or culture.’

19% reported ‘I have read racist messages.’

20% reported ‘other’.

Learners that told us about other kinds of ethnic bullying and racism that have happened to them in the last month. They described incidents of microaggressions and stereotyping.44

Microaggressions are brief, everyday interactions – spoken or actions – that communicate biases and negative thoughts and feelings about someone’s ethnicity and can have significant impacts on people’s wellbeing.

When looking at learner experiences, just under half (45 percent) of those students who reported an instance of racism in the last month had experienced more than one racist incident. More than one in five (23 percent) have experienced an instance of racism more than three times in the past month.

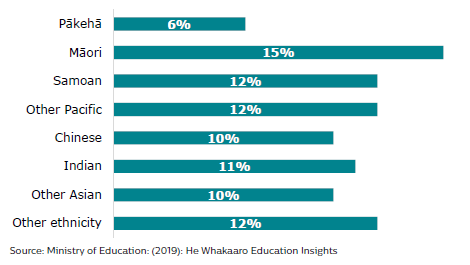

One in four learners reported their teacher has treated them unfairly due to their ethnicity in the past year. Learners from ethnic communities experience this significantly (see Figure 28).

Figure 28: Likelihood of being treated unfairly by a teacher due to their (students’) ethnicity in the last 12 months

Figure 28 is a graph showing the percentages of learners from the following ethnic groups who had been treated unfairly by a teacher due to their ethnicity in the last 12 months of learners.

6% Pākehā reported they had been treated unfairly by a teacher due to their ethnicity in the last 12 months.

15% Maori, 12% Samoan and 12% other pacific people reported they had been treated unfairly by a teacher due to their ethnicity in the last 12 months.

The percentage for Chinese, Indian and other Asians and other ethnicity were 10%, 11%, 10% and 12% respectively.

Data from 2019 shows that learners from ethnic communities experience a higher proportion of ethnicity-related bullying than their European peers. Ethnicity-related bullying also occurs more frequently for secondary learners who arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand more recently (i.e., are new migrants).45

A community leader told us:

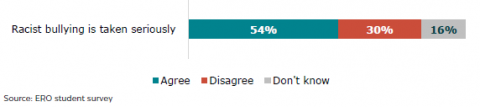

Spoken words can have long term negative impact. An Asian child did really well in school exams. Teacher asked the student ‘Did you cheat?’ This was so impactful for the student who has doubted their ability.

Both whānau and learners feel racism and racist bullying needs to be better identified and addressed by their school. Deeply concerningly, 30 percent of learners do not think their school takes racist bullying seriously (see Figure 29).

Figure 29: School takes racist bullying seriously (learner responses)

Figure 29 is a graph showing whether learners agree or disagree that racist bullying is taken seriously.

54% learners agreed.

30% reported disagreed.

16% don’t know about this.

This is in contrast to teachers, almost all (92 percent) of whom think racist bullying is taken seriously. This mismatch of perception suggests schools are not aware of the experiences of learners and whānau.

In our focus groups with learners and whānau, and in community hui and interviews, the need to better identify and address racism came through strongly. Some learners noted that teachers often disregarded or minimised their concerns about “microaggressions” or comments about ethnic background, and stereotyping ethnic or religious background. The inaction by teachers and a lack of clear boundaries about what is acceptable and not acceptable impacts on learners’ ability to counter these. Additionally, in several incidents, learners noted that leaders “took the teacher’s side or perspective” when learners reported racist encounters or incidents.

We need to talk openly about racism and discrimination in order to make significant changes. School staff needs adequate training on racism and discrimination. Schools need to have robust policies around discrimination, racism, bullying, etc. and need to make sure that every student knows where and how to reach out. Anti-racism work has to be done by everyone.

- From submission

Not being accepted and not belonging

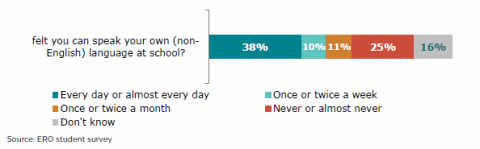

One in five learners from ethnic communities told us they have to hide their ethnic identity at least once or twice a month. The same proportion also feel excluded from activities at school because of their ethnic identity at least once or twice a month. One in four learners report they never or almost never feel they can speak their own language at school (Figure 30).

Figure 30: How often learners feel they can speak their own language at school

Figure 30 is a graph showing the frequency learners felt they can speak their own (non-English) language at school.

38% learners felt they can speak their own language at school every day or almost every day.

10% learners felt they can speak their own language at school once or twice a week.

11% learners felt they can speak their own language at school once or twice a month.

25% learners felt they never or almost never can speak their own language at school.

16% learners don’t know about it.

In focus groups and through community hui, learners shared instances of when they or their peers did not feel accepted due to their cultural identity. Much of this centred around cultural practices which differed from others, including religious practices, clothing, or eating.

I still feel kind of weird taking Indian food to school as you have to eat it with your hands. One of my friends—she is Indian too, got bullied so badly for her food (smelly) that she became a loner. And she tried to bring sandwiches to school even though she didn’t like them, but it was too late.

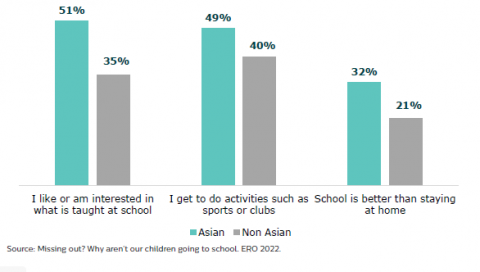

– Learner