Summary

Building genuine partnerships with parents to keep children learning

This report is part of a series about teaching strategies that work. It features strategies and approaches we saw in 40 primary schools across New Zealand.

We selected these schools from a database of 129 schools, all with rolls over 200 and all with increased numbers of students achieving at or above the expected standards as they moved through the upper primary years (Years 5 to 8). These schools’ achievement levels were also higher than the average for their decile. We asked leaders in each school what they saw as the reasons for their school’s positive achievement trajectory and then investigated the positive teaching strategies and resulting outcomes.

This report shares strategies and approaches from schools that had contributed to improving achievement by developing genuine learning partnerships with parents. It also includes some simple strategies a few of the schools used to involve parents more in supporting the things children were learning at school.

What ERO already knows about learning partnerships with parents

Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau (2015)

In the best examples in this report, teachers involved most parents in setting goals and agreeing on next learning steps with their child. Teachers responded quickly to information obtained from tracking and monitoring student progress. They persisted in finding ways to involve all parents of students who were at risk of underachieving, and ways for all students to succeed. During conversations with parents and whānau, teachers aimed to learn more about each student in the wider context of school and home, to develop holistic and authentic learning goals and contexts for learning.

Continuity of learning: transitions from early childhood services to schools (2015)

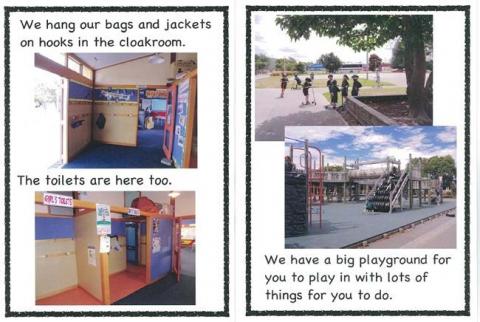

This report stresses how critical an effective transition into school is for a child’s development of self worth, confidence, resilience and ongoing success at school. Schools that were very responsive to ensuring children successfully transitioned could demonstrate they had real knowledge about their newly enrolled children. They took care to translate that knowledge into providing the best possible environment and education for each and every child. Leaders made sure transition was flexible and tailored to the individual child.

Partners in learning (2016)

Strong connections between schools and parents and whānau are essential to accelerating children’s achievement, particularly for those at risk of underachieving. This booklet helps parents, families and whānau to form effective relationships and educationally powerful connections.

What we found in the schools included in this evaluation

Most of the 40 schools had built good relationships with parents but had not fully developed genuine learning partnerships. All schools reported to parents and had interviews or three-way conferences and other communications with parents.

However, they hadn’t all fully given prominence to the culturally responsive concepts of manaakitanga, whanaungatanga and mahi tahi.1

Genuine learning partnerships

Some schools had seen considerable benefits for children from developing genuine and reciprocal learning partnerships with parents and whānau. These schools had been quite deliberate in their approaches. In some cases leaders and teachers had introduced new practices as part of a Teaching as Inquiry project. Some introduced improvements as part of their involvement in Accelerating Literacy Learning (ALL) and Accelerating Learning in Mathematics (ALiM).

Teachers and leaders examined research and trialled new practices in parts of the school or for specific groups of children before extending practices more widely across the school. Some schools worked closely with parents when they introduced new teaching approaches and strategies. They shared the intended benefits for children with parents and reviewed how new processes were working for them. Leaders and teachers in these schools also reviewed student achievement information before and after developing partnerships and found considerable increases in student achievement.

One of the key components of these genuine learning partnerships was the regular and honest sharing of all achievement and progress information teachers had collected. Teachers and parents looked at the actual assessments together and discussed the strengths and possible reasons for any visible progress or confusions for a child. In some schools this sharing was particularly evident in the first two years the child was at school.

However, in the best instances, high quality practices for working with parents went across all year levels and built on the partnerships established in those first two years. In schools where successful learning partnerships with parents are found solely in Years 1 to 2, these should be extended across the school to help address the achievement slump seen for many children in Years 5 to 8.

Differentiated approaches to working with parents

Some schools differentiated the extent of the relationship with parents depending on the strengths and needs of the child. Leaders in these schools recognised educationally powerful connections and relationships between teachers, leaders, parents and whānau as components of an effective response to underachievement. Teachers worked very closely with parents of children who needed to accelerate their progress. Teachers valued what the parent could do to help and went beyond just talking to the parent about what they could do.

They also listened to what the parent might suggest and acted on the suggestions. The partnerships resulted in consistent language, strategies and goals that children, their teachers and parents/whānau understood and used. Teachers valued the time spent on the partnership as it generally resulted in greater progress for the child and less need for additional instruction for the child in the classroom.

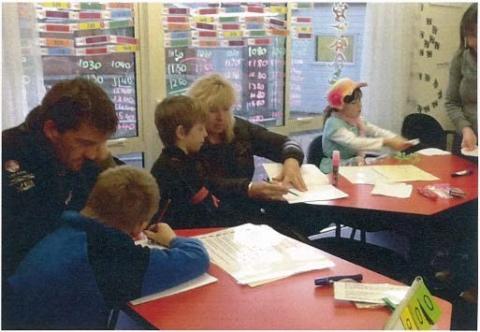

All the parents we spoke with who were involved in learning partnerships valued the opportunity to be fully engaged in their child’s learning, especially when their child had identified learning needs. Parents talked knowledgably about the strategies they had learnt, their child’s progress, and what they needed to do for their child to succeed. In the most successful schools, every parent was involved and contributing to their child’s learning. In some cases, teachers invited parents into the classroom to see the learning in action and had then resolved any concerns the parents had about their child’s learning. Parents expressed a real gratitude for the time teachers and leaders had taken to work with them to support their child and accelerate their progress.

Every parent of a child who needs support to accelerate their progress should expect to be fully involved and welcomed to contribute to that support. Parents know their child’s interests and concerns and can not only contribute to the child’s learning at home, but also help the teacher understand more about what gets in the way of their child’s success and what helps them succeed. In some of the schools, teachers were amazed by the amount of progress that occurred when parents knew the strategies they should focus on at home. Teachers also recognised how a child’s self esteem increased when both teachers and parents understood and responded to the child’s strengths, goals and interests.

Finding ways to involve parents in their child’s learning

Many of the schools featured in this report were in low socioeconomic communities where a high proportion of parents were fully involved in their child’s learning. Leaders and teachers in these schools avoided making negative assumptions about parents’ willingness to contribute to their child’s progress.

Instead, they:

- built strong and ongoing learning relationships with parents and whānau

- fully and honestly shared assessment information about the child

- listened to parents’ ideas about how they could help and what support they needed

- provided details about the language, strategies and approaches the child used at school

- provided materials and internet links for parents that needed them

- regularly communicated with parents to share and hear what was working and what they all (the child, parent and teacher) should do next.

The way leaders and teachers valued and worked with parents was key. Teachers did not just talk at parents; they worked with parents who could then fully contribute to their child’s learning. Every school had such productive and genuine learning partnerships, especially for children who need additional support to achieve success with some aspect of their learning. Partnerships established in Years 1 and 2 were built on further as the child moved through the school.

At the end of this report we include links to ERO’s School Evaluation Indicators along with questions for school leaders to consider when focusing on improving parent partnerships.

Whole article:

Building genuine learning partnerships with parentsThe parent partnership approaches and strategies that worked

In the following narratives we share the approaches and strategies of the schools that implemented deliberate strategies to improve their learning partnerships with parents. The list below highlights the key approaches in each narrative.

01. Moving to genuine relational and learning partnerships with parents, families and whānau

Belmont School, Lower Hutt

- Identifying the extent of their partnerships

- Changing to genuine partnerships

- Sustaining the improvements

02. Using and responding to an inquiry to improve learner- centred relationships with parents

Oratia School, Auckland

- The leader-led inquiry

- Other partnership strategies

03. Genuine, learning partnerships with parents to help both the children and the teachers

Papatoetoe North School, Auckland

- Seeking and using parents’ views and knowledge

- Sharing information and resources with parents

- Reinforcing the benefits of the parents’ role

04. Improving educationally powerful connections with parents

Christ the King School, Christchurch

- Early developments to engage parents of Māori children

- Partnerships with parents of children involved in interventions

05. Comprehensive information enables parents to support their child’s learning at home

Sylvia Park School, Auckland

- Collecting and sharing comprehensive assessment information

- Sharing information about children’s goals and next learning steps

- Involving parents in their children’s learning

06. Working closely with families to accelerate children’s progress in mathematics

Aberdeen School, Hamilton

East Taieri School, Otago

07. Working with parents during a child’s transition to and within school

Woodend School, Christchurch

Gleniti School, Timaru

Milson School, Palmerston North

08. Simple strategies that enhanced learner-centred relationships with parents

Teaching strategy 01: Moving to genuine relational and learning partnerships with parents, families and whānau

ERO’s 2015 report Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau found that a whole-school focus on involving parents and whānau was an important factor for building educationally powerful relationships. Some schools had positive relationships with parents and whānau, but few had genuine learning-centred relationships.

Leaders at Belmont School recognised that what they had assumed were learning partnerships in their school were in fact only positive relationships with parents. Previously they had mainly talked to parents, families and whānau and told them what teachers were doing or what the parents should do. They changed the balance of these conversations by listening more and responding to parent and whānau stories, ideas and views.

This narrative shares the process the school used to review their partnerships and the actions they took to build and maintain genuine relational and learning partnerships with parents, families and whānau.

The development of strong positive relationships had always been an important part of the school’s culture. ‘Succeeding Together’ underpinned the way they built relationships with their children’s families and whānau. This relationship building started from the time families considered joining the school and was strengthened in the way communication and reporting practices were maintained. The school’s mission statement, developed with the community, clearly espoused a desire to work together.

Mā te mahi tahi ka piki kōtuku

Succeeding Together

In partnership with our community, we will provide a dynamic, safe, learning environment of excellence, which prepares all our students for future challenges and a love of lifelong learning.

Ma te mahi tahi o te kura me te hāpori, ka ako ātātou tamariki i roto i te kura autaia, kura haumaru hoki kia tū tangata rātou i ngā āhuatanga katoa ō t ō rātou ake ao. Kia whāngaia hoki te hiahia motuhake ki ngā mahi katoa o te ako mo ake tonu atu.

Their recent changes centred around:

- identifying the extent of their partnership with parents

- developing genuine partnerships

- establishing the relationship with parents when children started at the school

- sustaining and building the partnerships.

Identifying the extent of their partnership with parents

Work on building genuine learning partnerships began when the school participated in a Learning and Change Network (LCN) cluster with several other schools. One of the activities the cluster chose to undertake was drawing ‘learning maps’. In this activity, children, parents and whānau were asked to draw a map explaining “what learning looks like for you”. The school also held a series of meetings with stakeholder groups, with each person drawing what learning looked like for them. They were prompted to think about the place of students and their peers, parents and whānau, teachers and technology in learning, and to position them accordingly in their drawings. Leaders analysed the ‘learning maps’ to help them fully understand who and what helped children’s learning.

The drawings showed considerable variation between the learning maps of the students and their families compared with staff. Students and whānau saw the teacher as the decision maker, while the teachers’ learning maps showed decision making as shared and collaborative. Leaders and teachers had thought their positive relationships with parents and 100 percent parent attendance at learning conversations (goal-setting interviews) indicated learning and decision making was a three-way process. They recognised that they certainly had positive relationships but these were not truly learning partnerships.

We were confronted with the fact that while we had secure and positive relationships with our community, the decision making rested fairly and squarely with the school and that ‘consultation’ was really just about ‘telling’ our families what had been decided, quite probably in the hope that they would agree with that! The dissonance was certainly uncomfortable but, to everyone’s credit, was seen as an opportunity and the mandate to make changes to what and how we were doing things.

Principal

Developing genuine partnerships

Leaders and teachers began a process to promote more listening and less telling or showing. Leaders realised they also needed to take a closer look at the unintended messages their forms of communication, and the language used, may have been giving. They decided to look in detail at what they were doing and how they could make changes to shift the power balance to genuine two-way partnerships. This change in approach was deliberate, planned and school-wide and, at times, challenged the ideas some staff and families had previously held about their roles and responsibilities.

Leaders and teachers began the changes by looking at their practice through a different lens. They had begun to inquire into how involved their priority or target students were in their own learning, and what effect this was having on their achievement and rate of progress. Leaders and teachers extended their focus to think about how involved these children’s families and wider community were in decisions about the curriculum and subsequent learning. Leaders recognised that many learners who were not making the expected progress were not actively contributing to or understanding their learning, at home or at school.

The board of trustees and the wider school community worked together to consider everyone’s involvement in decisions about learning. They began by attempting to define what being ‘active in learning’ looked like and what dispositions should be taught to children to achieve this. This working together was a considerable change from their previous practice of consulting or informing families and whānau of the outcomes. The process gave leaders a purposeful context for them to trial and practise inviting, establishing and developing a partnership. This was a chance for staff and parents to learn alongside each other.

Active role of learners

Students

- Take responsibility for making sure that we have an attitude of giving everything a go, solving problems and thinking about new ideas

- Make sure we are organised for learning

- Look after ourselves so we have energy for learning

Teachers

- Strengthen our ability to know what works best for each student

- Planning and reflecting on our own practice as active learners

Families/Whānau

- Students to be active, independent learners at home

Leaders

- Model active learning in all our practices

- Develop a picture of what active learning looks like and evaluate our practice accordingly

Parents’, students’, teachers’ and leaders’ perspectives and initial thinking were shared, clarified, valued and built upon during the development of ideas about active learning.

Progress with this work was communicated frequently and in different forms so ideas could be gathered from more widely than just those who were able to attend the meetings and activities.

The diagram above shows the definition of the active role of learners they decided on together.

Children told ERO they wanted ways to show their families how teachers taught things at school, so there wouldn’t be so many arguments when they did work at home.

During 2016, this collaborative work continued to bring together ideas about the dispositions of active learners. The community was working to fully explain how learners would connect to, question and reflect on their own learning. Children, families and staff were also:

- involved in the school’s teacher only day

- able to vote on how the definition of ‘active learners’ would be visually represented

- working together to describe the dispositions related to being resilient, resourceful and responsive.

Leaders changed the reports to parents to include these dispositions. Leaders felt the contribution of the school community had not only given themselves and teachers great insights into parent and whānau aspirations, but also helped everyone to have a deeper understanding of the expectations they were setting.

As this work progressed, leaders and teachers applied what worked to other aspects of school life. When teachers attended professional learning and development (PLD) designed to respond to the needs and strengths of specific children, then their whānau were invited to attend. Learning alongside each other meant resources were shared and children had consistent strategies and goals to focus on when learning at school or at home.

Establishing the relationship with parents when children started at the school

When leaders and teachers met with parents and whānau during a child’s transition to school, the focus also changed to encourage learning partnerships. The principal met with every family to show how they valued each child. They changed the timing for sharing assessment data and other information with parents from five weeks after a child started school to around three weeks after their start. This sharing of information during transition applied to all children starting at the school, not just new entrant children. The earlier the relational trust began to build, the more secure both the teachers and whānau felt about sharing information. As a result, more responsive and personalised teaching programmes were developed that built on each child’s strengths, interests and family values.

We changed to focus more on ‘hearing the story’. At the four-week transition meeting we share what we have found from assessments and other information, and ask parents and whānau if that sounds right, or is it what they would expect. We usually say something like “I have noticed…., what do you think, does this match up with what you see at home or do you see something else?”

We also ask about anything else that was happening at their previous school, or at their child’s preschool. We find that sometimes there are things they don’t tell us when they enrol the child that they are able to share at this assessment sharing meeting. Parents and whānau will usually only share this type of information if we have shown that we are really keen to listen and learn about the child.

Principal

A key expectation of leaders was that there would be no surprises for parents when they received written reports or if their child began any targeted intervention. Children, parents, whānau and teachers worked together to identify the children’s strengths and learning needs, set goals, and plan responsive strategies and actions. Teachers sent home information that was differentiated to respond to the strengths and needs of the parents and whānau. Before sending extra work home, teachers would usually talk with the parent first and offer activities like a game the child could play at home to help with an aspect of their learning. Teachers carefully designed home learning to be completed either independently or with the guidance of whānau. Both approaches were encouraged and valued.

When a child had additional help to accelerate their progress, parents who already knew their child’s strengths, needs and goals were in a better position to offer effective support with home-based tasks.

Building the partnerships

Working in partnership to gather evidence and share information around learning became more flexible. The initial hesitancy and even defensiveness around roles and responsibilities diminished as the confidence of staff and families grew. Staff commented on the increased initiation of conversations around learning by families as they were ‘dropping in’ more often to make suggestions. Issues and concerns seemed to have a problem-solving approach rather than appearing as an occasion to complain about the child or the teacher.

Questioning from parents was no longer perceived as a challenge to the teacher’s capability, but rather as an opportunity to achieve better outcomes for our children. Collaboration was a cause for celebration.

Partnerships in learning were not solely reliant on a physical presence in the school. With the increased use of technology, families were able to give ‘real-time’ feedback to their children as well as to follow progress and comment on blogs or Facebook, using emails, phone calls and the school website. Children sent a weekly email home about their learning, and regularly took their Chromebooks home to share their work. The school newsletter, which had traditionally gone out to families weekly, became redundant. Parents indicated that the more frequent and less ‘wordy’ communication from children and teachers was more effective. While they continued to have face-to-face learning conversations led by the child, these no longer needed to take place at the school.

Valuing diversity means looking at the way we have meetings, the way we write reports, having different meeting times so we hit a different audience. We will sometimes have meetings at 2pm because that is a time parents can come that coincides with their collecting children from school.

We have meetings at 7pm so working parents can come. We have dinner meetings.

With our maths meetings we had the same meetings at three different times for half an hour each, so that parents could go across the school teams.

We ask families what will suit them best and provide childcare.

We use Hutt City Church for assemblies, so we asked our Muslim families if that was okay for them. They were really appreciative that we asked.

Leaders

The tone, intent and variety of forms of communication had shifted. Team newsletters to parents moved from providing information about the intended curriculum focus and upcoming events, to seeking input and direction from whānau before planning the curriculum focus. Parents, whānau and the extended community were encouraged to share their perspectives, skills and expertise.

Teachers saw this gave children a much wider range of learning experiences in response to their specific interests. School was no longer perceived as the only site of learning.

One subtle change to reporting learning to parents

The children were already making choices about the artefacts that illustrated their learning during conversations, and when reporting achievement in relation to the National Standards. The simple action of leaving the ‘How you can help at home’ section blank in the conversations template and report meant it was up to the children, parents and whānau to make the decisions and not the teacher.

This change acknowledged and affirmed the important role and skills families brought to learning, and signalled the expectation that ‘we are all in this together’ and are all committed to achieving accelerated outcomes for children.

Sustaining improvements

As the changes to their approach were agreed by teachers, parents and whānau, it was important they were consistently applied. The fact that both parents and teachers knew what was expected made it easier for leaders to introduce a consistent application of the agreed approaches across all classrooms.

Additionally, leaders were keen to maintain the gains they had made in building whānau partnerships, and included the following expectations in job descriptions that were sent out to prospective staff:

Parents as partners in learning

- Whānau feel valued, welcomed and respectfully acknowledged by the way we collaborate and build relationships.

- There is regular communication with home, informing families about programmes and events.

- Deliberate actions are taken to communicate positive news.

- The teacher is available in the room for informal chats before and immediately after school.

- Whānau are kept fully informed of their child’s progress. Nothing should ever be a surprise in any formal reporting situation.

- Reporting is honest and professional. Success is celebrated and strategies for achieving next steps are identified and agreed in collaboration with parents.

- Issues are dealt with quickly and follow school procedures.

- Community skill and assistance is used where appropriate.

- Help is timetabled and roles are clear and supported.

- Confidentiality of each student and their family is mutually respected.

The person specification for new teachers stated that the successful applicant will (among other things) “have an open mind about the role of the teacher and be active in sharing decision making with students and their whānau”.

This will always be a ‘work in progress’ as the aspirations of the students and their families, the demands of the curriculum and the direction of educational thinking, and the makeup of the staff are dynamic and constantly changing. We have learnt that strong partnerships in learning are even more important in the tough times, and this is when we all have to work hardest at building and maintaining them.

Leaders

Teaching strategy 02: Using and responding to an inquiry to improve learner-centred relationships with parents

ERO’s report Raising student achievement through targeted actions stresses the importance of school leaders in increasing children’s progress. Leaders designed, resourced and carried out targeted actions that focused on improving both student outcomes and teaching. Leaders spread the actions across the teaching staff by using in-school expertise to accelerate learning. They aimed to have all children succeed.

Leaders at Oratia School saw the advantages of including parents when introducing any new programme or innovations. Their preparation for a new programme had to be thorough, grounded in research and shared with parents. They used and built on the strengths of staff, and communicated with parents and staff to make sure everyone understood and supported new programmes.

This narrative shares the inquiries and strategies the school used to develop successful learning partnerships.

Leaders and teachers initiated a strong focus on building genuine learning partnerships with parents. The community/whanaungatanga strategic priority for 2016 to 2018 was to foster a positive school culture, and strengthen home-school partnerships to support students’ engagement and achievement. Two of the specific priorities for 2016 were to:

- foster a collegial school culture based on mutual respect and trust

- strengthen home-school partnerships through improved communication.

Teacher-led inquiry

The focus on the parent partnership goal began through a teacher-led inquiry, and then a leader-led inquiry. The teacher-led inquiry began by focusing on a small group of boys that needed support to improve their writing.

The teacher hosted an information evening for parents and whānau of the group to explain what she intended to do, and what this would mean for her, the parents and whānau and the boys concerned. Before the parent evening, she shared part of her presentation with the boys to help them commit to being involved and understand her intentions.

She was open about the intervention being part of an inquiry and her learning when contacting the parents (as shown in the letter to parents below).

During the meeting, the teacher shared the strategies she was using and showed parents how they could reinforce them at home.

Our school encourages teachers to have a personal inquiry to improve their practice. My inquiry this year is: “How do I get my students to put into practice what they have learnt in lessons and apply it to independent tasks?” My goal is to raise achievement in writing. I have a target group of 11 boys that I am focusing on. Your boy is part of this group. I have already started the process and I am enjoying the group as they have a lot to offer.

I believe that a school partnership with home has a significant impact on children’s learning. Because of this I would love it if you could come to a parent information evening on Thursday…in the staff room.

At this meeting I will be covering the information below:

- How I have approached the boys about being part of this group.

- What my aim is.

- What I am doing in class to support their learning.

- How you can help.

- A quick practical workshop on how to access their blogs and how to use the Read/Write app.

I will also provide drinks and nibbles!

She had ongoing meetings with the parents to discuss their child’s learning at school and at home, and to set new goals. Feedback from parents and whānau confirmed they felt empowered and knew how to support their child at home with their writing. The children were accelerating their progress.

Leader-led inquiry

Subsequently, in Term 3, 2016, the senior leadership team decided to initiate a whole-school inquiry to extend partnerships with parents. Leaders specifically wanted to address the difference in achievement for some of their Māori students (most of whom were boys).

They identified children across the school who need to accelerate their progress. Early in the term the parents of these children each met with their child’s class teacher. They discussed the current level of achievement of their child in either reading, writing or mathematics. The teacher explained the desired level they wanted the child to be achieving. They aimed to have the children achieve at the expected curriculum level by the end of the year. The parents were told the specific goal their child was working towards and were given resources, such as flash cards and other activities that would help them to work on the goal with their child at home. Every two weeks the teachers and parents had contact (face to face, emails, phone calls) to discuss the achievement of the goals, and whether parents and the teacher felt the child was ready to move on to another goal.

Parents felt this connection had improved their relationships with the teachers as well as their child’s progress.

To avoid adding to the teachers’ workload, leaders used and extended some of the processes they already had in place:

- staff regularly updated the school’s website and Facebook calendars to keep parents well informed

- teachers sent parents a weekly email outlining the week’s events

- leaders reviewed reports to parents to reduce teacher workload and meet parents’ needs

- leaders reviewed meet the teacher, student-led conferences, open days, and other home-school events to make sure they were achieving their aims

- leaders established expectations to help develop and maintain the home-school partnership for learning.

Teachers changed their emails and blogs to provide more specific information about how parents could support their child’s learning at home. Actions to increase the partnerships supported all children, while giving additional emphasis to children who needed to accelerate their progress.

Working together to accelerate children’s progress

Teachers recognised that children needing additional support would make greater progress if they were supported to practise their new learning at home as well as at school. Regular contact with the parents of these children enabled teachers to learn more about each child’s strengths and interests and they were able to use this information to further engage and motivate the child. Working together with parents was vital to ensuring the children used consistent strategies at home and at school.

ERO met with a parent whose child needed extra support with reading. The child’s mother told us the child seemed to start well in the new entrant class but then didn’t progress well learning to read. She was contacted by the teacher who talked about the child’s progress.

The parent talked to us about many strategies the teacher had showed her including cutting up sentences from part of the story, and having her son put them back together. The parent had also worked on letter sounds. She could see she was working at home on the same things the teacher was working on at school. The parent and teacher met every two or three weeks to discuss her son’s progress.

My son knows this is helping him. He has improved immensely. He can now recognise words more without reading from memory so much.

The parent was grateful for the opportunity to help her son. Her opinions had been listened to and when she raised any concerns, adjustments were made to the programme.

Parents understanding their child’s goals

Children regularly set and shared learning goals with their parents. They outlined how they planned to achieve goals and timeframes for reaching them. Every week parents made a comment where they explained what the child was doing at home in relation to the goal. Sometimes, they noted the child was achieving their goal and suggested some ideas of what they could do next.

Many Year 6 children talked to us about the value of parents being more involved.

The goals help. They help focus when you’re writing something. You might be working on something like including complex sentences, and then the work you did at home becomes evidence to show the teacher that you have reached the goal.

Work at home is more related to the skills we are practising at school now that our parents are more involved. Our work at home is a continuation of our work at school.

Year 6 children

Parents understanding new teaching practices

Teachers had undertaken many inquiries into different teaching approaches. Whenever they planned a major change in approach, parents were consulted to determine its merit. Parents were shown parts of the research teachers had accessed and the likely benefits and challenges resulting from the intended changes. For example, when the teachers were considering introducing a boys’ Year 5 class, leaders held information evenings for parents of Year 4 boys and included links to relevant research. Leaders also made up information packs with more detail about the proposal, and extended an invitation for parents to meet with the principal to discuss any questions. Information about the class and its likely composition was also included in the newsletter to inform the wider school community.

Parents’ feedback about their children’s perspectives or concerns about new teaching strategies were sought and valued. Parents were also able to visit classrooms to see new teaching approaches. One parent had visited her child’s class to see the changes the two teachers had implemented to introduce modern learning teaching practices. Later the parent emailed the teachers to share what she had observed. Part of the parent’s observations are as follows.

I was really impressed by the way the children understood the routine and what was required of them. Also by the way all the resources they needed were readily available and they knew where to look for them. I finally understood how children managed themselves while you both took workshops. It was awesome to see the obvious satisfaction the children gained by being able to do their work in a place, and in a way that suited them, even in the short time I was there. I really didn’t know what to expect when I visited. Thanks for encouraging me to come in, and thanks for the obvious interest and effort you have put into this new way of learning.

Another parent had emailed the teacher to share a comment from their child.

Last week I asked **** how she was finding the structure of the class (because it is so different to the class she was in last year), and she said, “It’s the best class I’ve ever been in.” I asked her what she liked about the structure and she answered, “They trust us to make decisions.”

This and other parents’ affirming feedback contributed to the decision to extend modern learning practices more widely across the school.

Outlining partnership expectations

Together staff had agreed the practices listed below to maintain and reinforce home-school partnerships. Leaders were intending to continue to inquire into, and build, the partnerships further in 2017.

Schools and teachers who value the intent of this relationship:

- know about, care and build on each learning experience, removing the separation between home and the learning experience

- use a shared language about learning and achievement with students and parents/whānau

- value the wellbeing of ākonga (students) and are interested in them and their whānau

- involve families and whānau in setting goals for children

- regularly connect with families to review their working relationships

- communicate with families and whānau

- persist in ways to involve parents and ways for students to succeed, and treat families with dignity and respect.

Parents who value the intent of this relationship:

- treat their child’s teacher with dignity and respect as they work together in pursuit of the best outcomes for each child

- are available and make time to communicate with their child’s teacher about the next learning steps for their child

- persist in finding ways to work with their child’s teacher so the relationship is one of mahi tahi – deliberate two-way, collaborative relationship focused on providing students with extended learning opportunities and increasing education success

- work collaboratively with the teacher to set learning goals for their child.

Teaching strategy 03: Genuine, learning partnership with parents to help both the children and the teachers

ERO’s 2015 report Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau identified that some schools had limited expectations that all parents could contribute to learning-centred relationships. In schools with low quality learning-centred relationships with parents of children at risk of underachievement, teachers and leaders believed they could only reach a certain proportion of parents, and that the lack of involvement of hard-to-reach parents was justified.

Leaders and teachers at Papatoetoe North School were able to successfully reach and fully involve a high proportion of parents of their children. Because leaders and teachers valued parents as children’s first teachers and as partners, parents were strongly committed to supporting their children’s learning.

This narrative shares how genuine learning partnerships benefited children and teachers in a school where the majority of children enrolled were Pacific, Māori or Indian. Parents supported children’s learning before and during children’s new termly topic studies that they called inquiry topics.

An outstanding feature of the school was the deliberate and successful focus on teachers and parents working together to improve children’s learning.

Leaders and teachers used many approaches to build and maintain such a successful partnership with parents:

- Listening to parents, to confirm for everyone involved in teaching the children, that parents hold high aspirations for their education and future.

- Providing home learning during the holidays that leveraged children’s strengths, interests and rich culture. This built children’s academic vocabulary to increase their knowledge before beginning each term.

- Providing parents with information and resources and teaching them strategies so they could help their children with their home learning.

- Making sure parents knew how their efforts were benefiting their children, as well as benefiting the children who hadn’t done the holiday work, through the increased richness of each class’s oral language environment at the start of each term.

Leaders stressed the importance of building on children’s existing content knowledge by using the rich cultural contexts children were already familiar with (as shown in the school’s diagram below that leaders shared with families).

We know two compelling facts

- First: you are your child's first and best teacher

- Second: What your child already knows about the content is one of the strongest indicators of how well they will learn new information

- You have the skills and knowledge to help your child learn and grow

- Your wonderful language and experiences are gifts you can share

- Taking part in the home school partnership has benefited your child, your family and the school

Seeking and using parents’ views and knowledge

Parents played a key role working with the ‘knowing the learner team’, which represented the major cultural groups at the school. The team led hui, fono and other meetings, where they discussed the focus with the parents. The knowing the learner team was then responsible for making sure the children’s cultural perspectives were included in each term’s inquiry plan. Consequently, each plan leveraged children’s prior knowledge and they began learning about each topic with what they already knew.

Parents of Pacific children worked in groups to discuss questions such as:

- how can you as Pacific parents raise the attainment levels of your children?

- what aspirations do you have as Pacific parents for your children?

- what values and perspectives about ‘environment’ have been taught to your children?

Usually about 40 to 50 parents came to each fono. Sometimes they discussed their views with people from the same culture and sometimes they chose to work with parents of children from similar year groups.

At the end of this fono:

- parents told leaders they felt they had been heard, and were confident in their ability to help children with home learning

- the teachers’ relationships with parents were enhanced, and teachers’ appreciation of parents’ high expectations for their children were confirmed

- a deep partnership to accelerate the start of each term’s inquiry learning, through holiday home learning, was established with the majority of the parents

- parents understood that if their children were one of the more than two-thirds of the class that undertook home learning, they were promoting the learning of the children who had not participated, through increasing the richness of the oral language in each class at the start of each term

- parents felt more confident to come back to classroom teachers to clarify their knowledge or strategies.

The knowing the learner leaders shared parents’ ideas with staff to use for planning the children’s inquiry topics. They also led staff meetings to make sure teachers understood cultural perspectives, and were empowered to include these in learning experiences. On one occasion, teachers completely changed their planned science experiments to take account of parents’ suggestions. They had initially intended to investigate the different states or properties of water (ice, water and steam) with Years 5 and 6 children. However, parents suggested they should use cocoa instead as it was something every family used. Subsequently, the children enjoyed making Koko rice as part of their investigation.

In another example, when the knowing the learner team planned a topic on sustainability, Tongan families shared with them their experiences of cyclones and Samoan families shared their experiences with cyclones and tsunamis. They also looked at the rising sea levels in Levuka.

We capture parents’ perspectives and play them to the staff to keep the perspectives and background of the children to the forefront. We want teachers to use what children know already, let them teach you and don’t be afraid of their culture.

Knowing the learner team leader

Some of the information parents shared with teachers before the sustainability topic is shown here.

Sustainability unit

Cultural competencies – Tangawhenuatanga, Ako, Wananga

Māori perspectives

Shared information about the following:

- Hauora – a holistic approach to wellbeing – seeing sustainability in the same way where it is difficult to separate the land, sea, waterways, air. Everything is linked.

- Kumara history from migration and uses for food and medicine. Harakeke versatility, sustainability and medicinal.

- Department of Conservation internet sites.

- History of Papatoetoe internet sites.

Pasifika perspectives

There are many stories of communities and small villages that are experiencing economic growth as the people are recognising the ‘treasures of the land’ and being supported by international groups to create sustainable businesses that enable them to earn wages and be able to live, work and create traditionally organic products in their homeland. They listed internet links about:

- Pacific products

- business launches

- vanilla beans

- Nonu Plant

- building climate resilient and food-secure communities.

Indian perspectives

- The hand-loom industry of India has a legacy of craftsmanship that gives self-employment to thousands of villages in India.

- Ayurvedic medicine is sustainable in India as it is plant-based and mostly herbal. It has historic roots from more than 5000 years ago.

- Provided internet links to these for teachers.

A mathematics workshop for parents was one of the requests leaders responded to that came from the hui, fono and other meetings. Leaders and teachers subsequently set up different mathematics activity stations in the hall and in classrooms where parents could try some of the activities with their children.

Teachers were available to support those parents who needed to clarify their ideas. Other staff looked after younger children so parents were free to focus on the mathematics.

The fono, hui and other meetings gave teachers some general information about children’s cultures and interests at home. However leaders recognised that they needed to extend the partnership to learn more about individual learners and their families. Leaders and teachers wanted more information to accurately build on individual children’s content knowledge and to increase their achievement and progress.

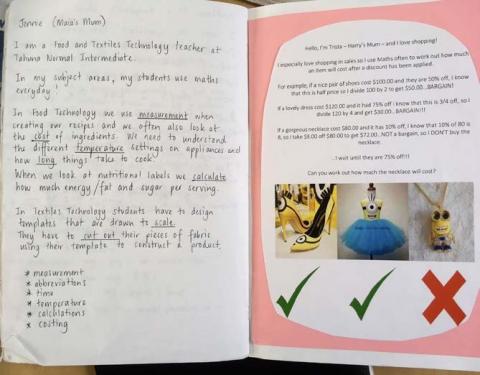

Providing information and resources for home learning

Home learning was completed in the holidays (including the summer holidays). Children were encouraged to “have fun during the holidays but don’t stop learning.”

Three teaching teams created meaningful home learning activities. In Years 3 to 6, for example, the focus was on the children exploring with parents what they already knew (including necessary vocabulary), and what they wanted to discover more about. As far as academic vocabulary was concerned, the emphasis was on hearing and valuing the family’s perspectives, not on looking up the dictionary or searching the internet for word meanings. The information given to parents in the home learning books also included advice about how they were helping their child’s teacher as well as their child.

For Years 5 and 6 children, some of the holiday home learning activities completed before the sustainability homework included:

- a brainstorming activity to show what the children knew about sustainability and what they would like to know

- finding and sorting man-made and natural resources

- drawing things in your environment that you see or wonder about whether they are sustainable – I observe, I think, I wonder

- vocabulary activity for eight new words

- a graphing and statistics activity.

Each term, leaders and teachers invited parents to the school to collect the home learning pack. Parents wanting extra support could participate in workshops about motivating strategies, or meet with teachers to go through the activities while their children would be supervised in the school hall. Parents were welcome to take home any resources they required. When teachers talked to parents, they shared what they would do at school for the child and then heard or discussed what the parent would do at home.

ERO met with a small group of parents to get their perspectives of the home learning and looked at many children’s home learning books. Although the parents we spoke with all told us they hadn’t done well at school, they confidently shared highly effective teaching practices they had used with their children. In most cases, they had worked individually with their children, using different approaches for their different age levels. The work in children’s books showed many parents had helped their children extend well beyond the original tasks. Some parents took photographs of their children participating in activities in the community, church or home that clearly shared their interests and strengths. The high quality work seen in the home learning books reflected the high expectations parents had for their children.

Children also showed a high level of commitment to completing the home learning with their parents.

In one Year 3 class, we asked a child to show us her home learning book. Other children scrambled to show their books and some of the work around the room they had completed at home. One boy proudly showed that he had done two terms’ holiday home learning in the previous holidays. When asked why, he said he had gone home to Fiji in the previous holiday and couldn’t do it then so he did it to catch up.

Another Year 3 child told us,

“Mum writes the words down and talks about them and I have to write a sentence about words like communities, enrich, inspire. Mum also gets me to learn how to spell the words but we don’t have to do that. This term our topic is creativity. At school, the teacher asks us what the meanings are. I made a new game with Mum this holidays to show my creativity.”

We asked a Year 6 child if he preferred to do the home learning independently now, but he said that he didn’t as his parents still had some good ideas.

Another Year 6 child said,

“the holiday homework not only helps us but gives us a heads-up of what we will be learning the next term and helps us understand the topic or concept.”

One child talked about how his older sibling at intermediate helped him. He proudly showed us the page in his book where his brother had helped him solve a problem.

A lot of the children’s home learning relating to the inquiry topics was displayed in classrooms. Teachers were able to learn about the child’s interests and culture and included these where relevant, in lesson plans and everyday conversations.

Reinforcing the benefits of the parents’ role

At the end of each term, parents came to an assembly where children from each of the teaching teams shared learning from that term. Leaders and teachers saw presentations as ways for children to share their learning, celebrate what they have learnt at school and home, and to use much of their new vocabulary.

ERO attended an assembly where children shared highlights from the previous term. Children confidently used the academic language introduced as part of the previous home learning. They also acknowledged the help they had received from their parents. Years 1 and 2 children talked about innovations they’d worked on at home to solve a problem they’d identified.

“My problem was that me [sic] and my sister always fight over a dolls’ house someone gave us. We decided the solution was to make another one out of cardboard. We got the cardboard from school to make it. My Mum came up with the idea, and my Dad worked nearly all night to help me. I am really proud of my dolls’ house and that my parents worked hard to help me.”

Year 2 child

At the end of the year, parents of well over 600 children who had completed more than 80 percent of the home learning came to a special assembly to celebrate what had been achieved. As they entered, each child gave their family the lei they were wearing. Children from each year level shared how they had benefited and what they had learned from their family or whānau and thanked their parents and whānau. Some of the work shared by children in Years 4 to 6 is below.

The school’s genuine learning partnership with parents supported children and their teachers. It also contributed to the positive and respectful relationships children had with their parents, as they valued the extra and visible effort their parents had put into helping them to learn. The home learning partnerships strengthened children’s sense of belonging and connection to school, whānau, friends and community.

Teaching strategy 04: Improving educationally powerful connections with parents

ERO’s 2010 report Promoting success for Māori students: schools’ progress explained that a factor commonly associated with the most effective schools was that parents and whānau were actively involved in the school and in students’ learning. Whānau had a sense of connectedness and a voice in determining the long-term direction of the school.

Teachers and leaders at Christ the King School had begun extending and improving the ways they engaged with parents of Māori children. They were also developing learning partnerships with the parents of children involved in targeted interventions.

The first section of this narrative shares the school’s developing engagement with parents and whānau of Māori children, and the second section focuses on partnerships with parents of children involved in targeted interventions.

Early developments to engage parents of Māori children

The work to improve engagement with whānau of Māori children began with a survey created using Google Forms and sent by email. Over half of the parents surveyed replied to questions about:

- how well Māori culture was enhanced at the school

- how well Māori students’ achievement needs were catered for

- how well informed whānau were about Māori students’ achievement

- what else the school should do to improve Māori students’ success

- whether they would support the introduction of group meetings for parents of Māori children

- other things whānau would like to see to enhance Māori culture at the school.

The survey responses highlighted many areas to develop along with approval for whānau hui. Suggestions included greater support for children and whānau during transition to school, more opportunities to meet Māori whānau in the local community, and for staff and children to visit the local marae. Leaders also worked with staff to review the teaching of te reo and tikanga Māori across the three teaching syndicates and to look in depth at the achievement of Māori students.

Since the survey, the school has started holding a Māori Aspirations Hui.

During the first few hui, the board and leaders established strategic goals to build teachers’ and children’s knowledge of te reo and tikanga Māori. They worked to strengthen links and create learning opportunities with whānau, the local marae and the learning cluster the school worked with. Leaders shared data about achievement levels and posed questions to discover parents’ aspirations for their children as learners.

At one hui, a staff member shared his whakapapa which encouraged some of the children and parents to go to their grandparents to learn more about where they had come from.

Partnerships with parents of children involved in targeted interventions

Many of the strategies for working more closely with parents of children receiving additional support came from staff involvement in the Ministry of Education’s Accelerating Achievement in Literacy (ALL) project. Before the children began working in the groups, their parents met with teachers to discuss how they could both support each child’s engagement and achievement in writing. The school also gave parents an information pack explaining the intervention. All parents in the school were invited to an explanatory session about the ALL project, where leaders and teachers shared and discussed the reasons for the school’s involvement.

Children’s writing was regularly shared with parents, who were encouraged to provide regular feedback. Teachers gave parents guidelines for providing feedback, and they communicated with parents about this valued feedback.

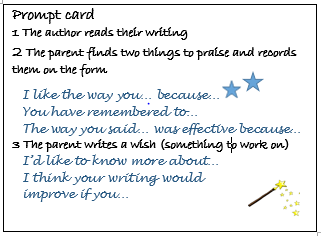

They gave parents prompts and feedback sheets adapted from The Writing Book (as shown here), with two stars as praise and one wish as something to work on next.

The sheet reads: "Prompt Card,

1. The author reads their writing

2. The parent finds two things to praise and records them on the form

[Written in blue] I like the way you.. because..

You have remembered to..

The way you said.. Was effective because..

3. The parent writes a wish (something to work on)

[In blue] I'd like to know more about..

I think your writing would improve if you..

The top of the sheet reads "Two stars and a wish". Below there are three boxes to fill in with prompts from the previous image.

Assessment data highlighted the positive impact of parents’ contribution (results are shown below). Further analysis showed the children in the intervention who made the most progress also had the most involvement from parents. At the end of the intervention, the parents joined the teachers and their children to celebrate the children’s writing improvements.

Results from the 14 week intervention:

- 45 Years 3 to 8 children were involved in the intervention

- 18 had now reached the expected curriculum level

- 13 moved two or more asTTle sublevels of the curriculum

- 8 moved one sublevel

- 5 remained at the same level

- 1 had left the school.

Teachers surveyed, and received written feedback from, parents about the changes they had noticed in their child’s writing and attitude to writing.

Eighty percent of parents responded to the survey and most were positive about the impact for their child. Teachers realised that to sustain and extend the progress they needed to continue to increase and maintain parent involvement.

Over the past few years, the school had steadily increased strategies to include parents in their children’s learning. Teachers informed and involved parents when their child took part in any intervention to support the child’s accelerated progress. Parents could observe targeted intervention programmes in action, and were given resource packs to support their child’s improvements at home. Ongoing communication between teachers and parents helped to identify, understand and focus on each child’s next learning steps. Learning-centred partnerships with parents were increasing and valued.

After the ALL project was completed, teachers still shared children’s writing regularly with parents. Children in Years 4 to 6 who needed an extra focus on writing took part in the Writing Café. Teachers sent children’s books home weekly to parents who discussed it with their child and added written feedback. Children in Years 4 to 8 also shared their work with their parents on Chromebooks that were taken home every day.

ERO met with a parent of a child involved in the ALL project.

The parent was pleased the school had identified the need for their daughter to have extra support rather than the parents having to ask for this. The mother liked the way the school had framed the support; the changes were not done to her daughter but planned with her.

“The biggest thing was that it was never implied that she had missed something or there was some type of deficit. Instead my daughter talked about how she was still learning how to work successfully.”

The parent also appreciated:

- how the extra support was carefully timed so her daughter didn’t miss out on other core learning

- the feedback her child received from the teacher, sometimes with the parents present

- improved confidence with writing generated an improved interest in reading, as the child saw that she was capable of reading texts at a higher level

- the way the child’s self-image changed, as her daughter could see how to make improvements and saw herself as capable.

The child was in Year 7 and now creating quite in-depth writing that was more interesting and fun. Her parents and the child love reading her writing now.

Their whole family benefited from being involved in the intervention, as their knowledge of both writing strategies and feedback helped them to support their younger children. They introduced their children to a wider range of texts at home, and encouraged diary writing to show they could write about their interests.

Teaching strategy 05: Comprehensive information enables parents to support their child’s learning at home

Two barriers ERO identified in the 2015 report Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau were a lack of assessment for learning and limited school-wide response to engaging with parents.

Leaders and teachers at Sylvia Park School took a deliberate approach to remove these and other barriers, and aimed to develop genuine reciprocal relationships with parents that ultimately benefited children, teachers and families.

They quickly carried out comprehensive assessments with children new to the school, to share with parents early as part of establishing their learning partnerships. As a result, parents were able to support children’s learning at home.

This narrative shares the different strategies the school used to fully engage parents in their child’s learning, and to ensure respectful relationships and collaboration between parents and teachers.

The school’s leaders had a strong belief that parents should have a right to access important information about their children’s learning, achievement and progress.

The community needs to be participating in our learning. What can 550 people do together to improve learning in our community?

We want to create high decile demand for information for, and involvement from, parents in a low decile school.

Principal

When a new family came to the school, leaders and teachers shared everything. For example, teachers displayed the junior reading levels as a colour wheel, and fully explained the numeracy stages so “parents didn’t have to operate in a fog”. Leaders showed every space in the school to demonstrate that everything was shared and nothing was hidden.

Collecting and sharing comprehensive assessment information

Teachers shared all assessments and the children’s responses with their parents. Teachers and parents:

- discussed what an assessment revealed

- jointly decided the child’s next steps as specific learning goals

- determined how the parents could support the child’s learning at home and how the teacher would support the learning at school.

Teachers also gave parents appropriate resources to support the learning goals at home.

Leaders prioritised children’s success from the outset. Their home-school learning partnership – named Mutukaroa – focused mostly on children’s progress and achievement in their first three years at school.

However, once the relationships were established, parents continued to work in partnership with teachers, to discuss and share information throughout their children’s time at the school.

Teachers undertook assessments immediately and regularly to quickly build learning-centred relationships with families and whānau new to the school. Whether children arrived at the beginning or during the year, the expectation was they would start learning straight away. They were assessed during their first week of school, again at six and 12 months, and after two years.

Teachers shared assessment data with parents and children, and used it to determine appropriate learning activities for home and school. The school employed an additional teacher to release the teachers to do all the Year 1 assessments. Parents who spoke to ERO saw how much learning happened in their child’s first year at school and could see the benefits of the learning partnership.

The school made a video (available on YouTube) that gives more detail about how leaders and teachers work in partnership with parents.

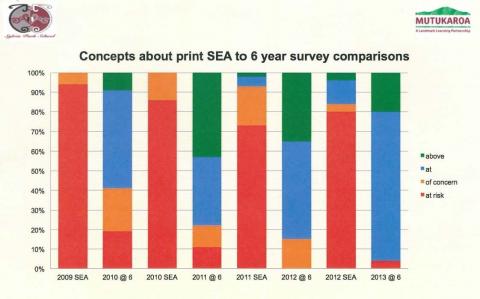

Considerable improvements in achievement were evident from the time teachers started working closely with parents in 2010. The graph below shows the improvements in the Concepts about Print school entry assessment (SEA) compared to when the children turned six (@6), when parent partnerships were improved. The graph shows that each year, not only the number of six-year-old children at risk and of concern reduced considerably, but the number of five-year-old children achieving at or above when they started school also increased. Working with parents may also have helped younger siblings because of parents’ increased knowledge of early literacy learning.

2009 SEA: at risk 94%, of concern 6%

2010 @ 6: at risk 19%, of concern 22%, at 50%, above 9%

2010 SEA: at risk 85%, of concern 15%

2011 @ 6: at risk 11%, of concern 10%, at 37%, above 42%

2011 SEA: at risk 72%, of concern 21%, at 5%, above 2%

2012 @ 6: of concern 15%, at 50%, above 35%

2012 SEA: at risk 80%, of concern 4%, at 12%, above 4%

2013 @ 6: at risk 4%, at 76%, above 20%

Sharing information about children’s goals and next learning steps

Children regularly shared their portfolios containing evidence of their learning in reading, writing, mathematics and inquiry topics. To increase their understanding of their own learning, the expectation was that as children moved through the school, they would increasingly be involved in assessing their own work. In Year 1, the work samples were accompanied by teacher comments. In Year 2, the teacher would write in consultation with the child why they had chosen to share this piece of work, and how it related to the success criteria. From Year 3 onwards, students were responsible for explaining why they had chosen to share each different piece of evidence.

“I have chosen this piece of evidence because it shows I can use doubling and halving to help me work out multiplication problems easily.”

Year 5 boy, mathematics sample.

“I have chosen this piece of evidence because it shows I have used paragraphs, commas and exclamation marks when writing a recount.”

Year 3 boy, writing sample.

In portfolios for children from Year 6 and above, we saw that children were confidently writing next steps for each work sample. This process, used with the portfolios, helped children understand what they had achieved. It also simplified assessment and tracking for teachers, and highlighted the child’s progress to parents.

Teachers and children shared reports to parents at both the midyear and end-of-year reporting conferences. During these three-way meetings, children, parents and teachers discussed:

- how the child was achieving in relation to the expected standards

- what the child could already do

- the child’s next steps

- how to help at home.

ERO met with a small group of Pacific parents who said they appreciated the sharing of information and resources, and attributed the increasing number of children reaching the expected standards as they got older to this sharing. They liked knowing about their child’s learning and getting very specific information about their child’s goals. One parent had enrolled her children at the school specifically so she could be more involved in their learning. The previous school gave her reports and talked about what her children couldn’t do, but wouldn’t show the actual assessments her children had completed or provide key information about how to help with learning at home.

“Our children know what they have to do at school. They have set their goals and they say what they are going to do to get there.”

“When the teacher showed me my boy’s reading assessments we could see that it was comprehension of the story that was holding him back. I had to try to keep up with his reading. My son told me what he had to do to keep up.”

“We are able to follow the curriculum and then we can set the bar high. We are given the resources. With the right resources our children can learn.”

“Everyone talks about learning here. Children talk about what they have to do.”

“My kids are proud of me for supporting their learning. It is important for me to be there for them, lifting them up.”

Parents

Involving parents in their children’s learning

Parents had many opportunities to be involved in children’s inquiry learning. They could attend weekly assemblies where the children shared their learning. They could also read about the ongoing learning in class blogs and find other information on their school’s website. The school also invited parents to participate in any vote or decisions about which of the children’s designs should be constructed or featured as outcomes from termly inquiry topics. Often, the outcomes also included things that would benefit the community.

The Sylvia Park School Hub gave parents many links to help with reading at home, along with good sites for more information about the topics children were interested in. You can find these links and other information about Mutukaroa: Home-School Partnerships on the school’s website.

The students’ learning came alive through the school’s work with the community. The outcome of every teaching topic was shared with the community at the End of Term Reveal, where everyone came together to celebrate the learning outcomes. The number of parents attending this End of Term Reveal was so large that the event had to be held in the local movie theatre. Children were empowered because they knew their learning would come to life through the inquiry outcome approach.

Parents we spoke to were proud to see their children’s learning prominently displayed in the school environment. They brought visiting friends and whānau into the school during the weekend so they could share their children’s achievements with them.

Teaching strategy 06: Working closely with families to accelerate children’s progress in mathematics

ERO shared details about positive relationships when responding to underachievement in Educationally powerful connections with parents and whānau.

Leaders and teachers at Aberdeen School and East Taieri School identified the learning strengths, needs and interests of the children along with their parents’ aspirations for them. The school responded to underachievement with deliberate actions and innovations that involved parents and whānau. Then they responded to those that worked for each child and refocused on the next actions.

Leaders and teachers at the two schools responded to an annual charter target to raise children’s mathematics’ achievement. They focused on the children needing to make the most progress. During their trials, they recognised the value of involving parents more when responding to underachievement.

Aberdeen School

Leaders and teachers worked closely with 22 children who were below expectation in mathematics and involved their parents so they could increase the children’s progress. They met with the children just before the school holidays. They explained that the children could make good progress if they did some extra work over the holidays.

Teachers said to the children, you’re really close to where you need to be for your age and with a little bit of extra effort you can get there. The teachers put together work for children to do over the holidays, matched to the skills they needed to focus on.

We contacted the parents and said something like your child has the potential to reach the standard if we work together. They wanted to know how they could help, as we said we would give the children things they needed to work on and give the parents really specific examples of how to help. The parents were all on board and were really pleased we were doing something.”

Deputy principal

Teachers gave each child a personalised set of mathematics problems to solve. They were different for each child as they focused on what each child already knew and could build on. Teachers also provided examples of strategies children could use to help them and their families/whānau. Almost all the children completed the extra work successfully during the holidays.

At mid-year parent interviews, teachers shared successes with parents and explained the next area of focus for their child. Teachers continued the personalised books for targeted children. Every activity in the book was included for a deliberate purpose. The teachers didn’t want to overload children, so they included a variety of ideas such as family games and activities.

At the end of the year, they had a celebration. Only two out of the 22 children did not complete the homework activities. This reinforced for the teachers that parents could make a difference. Many parents came in afterwards to personally thank their child’s teacher for providing the maths work. At the middle of the year, 64 percent of Year 4 children were on track to reach the expected level. At the end of 2016, teachers identified 88 percent of children as being at the standard in mathematics.

Children had responded really well to the extra mathematics work. They enjoyed working with their parents and grandparents. They told ERO evaluators they were keen to continue over the coming Christmas holidays. Some of their comments are shared on the next page.

“I’ve been learning lots and lots at school, and lots and lots at home. We did some holiday maths so that we could get onto Level 2. I got a lot of help because some was pretty hard and my Grandad said, “I’ll come and help you.” Since I kept practising, I moved up a level.

Grandad was really proud of me.”

“I got really, really better. It was awesome. You got to learn stuff that was easy but the right level. Everyone got the right level for them.”

“I knew some times tables but I needed to know more. I practised every day – I had cards and I flicked them over ‘til I got them. My sister tested me.”

“My Mum was proud of me too. I am really good at gymnastics but I stopped for 3 or 4 weeks so I could do better at school. I am really good at gymnastics.”

“I’d like to do one for this holidays [over Christmas] but bigger and more challenging.”

Year 4 children

East Taieri School

Many of the improvements in the ways teachers worked with parents resulted from their involvement in the Ministry of Education projects, Accelerating Learning Literacy (ALL) and Accelerating Learning in Mathematics (ALiM). Teachers met with parents before, during and after each child was involved in the ALiM intervention. During the intervention, they aimed to involve parents in authentic mathematics learning with their child. They also built on existing practices such as involving parents in mathematics evenings where children ran some of the sessions.

We run a maths evening every second year for our school community. It is very successful in terms of participation. We always have a large crowd where about 75 percent of our school community come. We have about six to eight children from our classes running knowledge or strategy examples sessions. If you have the children run it and do the teaching, you get the parents.