Summary

This report presents the findings of ERO’s evaluation of how well 68 secondary schools in Term 1 2014 promoted and responded to student wellbeing.

Whole article:

Wellbeing for Young People's Success at Secondary SchoolForeword

The wellbeing of our young people is central to their success as confident lifelong learners. Wellbeing is a concept that covers a range of diverse outcomes. All definitions of wellbeing in schools assume that young people play an active role in their own learning and in developing healthy lifestyles.

Our education system maintains a focus on wellbeing from the time a child starts early childhood education until the time they leave secondary school, through the early childhood curriculum Te Whāriki and The New Zealand Curriculum for schools.

But in our complex and changing society, children and young people face an increasing number of issues that can seriously affect their wellbeing.

Recognising the challenges that a growing number of young people face, Prime Minister John Key launched the Youth Mental Health Project in April 2012. The project aims to improve outcomes for young people aged 12 to 19 years with, or at risk of developing, mild to moderate mental health issues. This report about wellbeing in secondary schools is part of ERO’s contribution to the project. It complements ERO’s report on wellbeing in primary schools and supports our development of indicators for student wellbeing. These indicators describe the values, curriculum and systems that help students experience a high level of wellbeing.

This report shows that while many young people are happy and enjoying school, some struggle with the volume of assessment. They could benefit from schools reviewing their assessment practices and involving students more directly in decision making.

Parents and whānau can work with schools to improve the wellbeing of our children and young people to help them become confident lifelong learners. This report gives you an insight into what’s important and what works well in schools to support wellbeing.

Iona Holsted

Chief Review Officer

Education Review Office

February 2015

Overview

Most young people in New Zealand are creative and resilient and thrive during their adolescent years – but 20 percent exhibit behaviours or emotions or have experiences that put their wellbeing at risk. The Prime Minister’s Youth Mental Health Project1 was established because of these concerns.

Part of ERO’s involvement in this project was the Wellbeing for Success: Draft evaluation indicators for student wellbeing (draft) 2013.2 The indicators describe the school values, curriculum and systems that help students experience a high level of wellbeing during their school years.

ERO evaluated how well schools promoted and responded to student wellbeing in 68 secondary schools (Years 9 to 13) in Term 1, 2014. ERO also evaluated this topic in primary schools – the findings for schools with Years 1 to 8 students are presented in Wellbeing for Children’s Success at Primary School.3

ERO found that support for wellbeing varied across the schools sampled. In general, secondary schools promoted wellbeing through the school values and curriculum. Wellbeing issues were responded to at an individual or group level and there was often specialist support for students with particular needs.

Eleven of the 68 schools sampled were well-placed to promote and respond to student wellbeing. They had cohesive systems aligned with their school’s values. Most students experienced high levels of wellbeing and found school rewarding. Another 39 schools had elements of good practice that could be built on. Eighteen secondary schools sampled had a range of major challenges that affected the way they promoted and responded to student wellbeing. Some of these schools were overwhelmed by their issues and unable to adequately promote student wellbeing.

Students in well-placed schools experienced respectful relationships with their peers and with adults that were based on shared values. Students were seen as inherently capable and expected to contribute to, and be accountable for, the experiences of others. Schools’ responses to anti-social behaviour, student truancy or lateness were consistent and aimed to build and restore respectful relationships.4 Good care systems ensured any wellbeing issues were minimised, so that the ability of students to learn was not compromised. These schools understood the benefit of connecting care information with academic information when identifying and responding to wellbeing issues. Students had easy access to high quality counselling and health professionals. Approaches to wellbeing were reviewed using consultation and in a timely way. The schools were focused on making improvements.

In general, students would benefit from more teachers and leaders asking them about their experiences and involving them in decisions about the quality of their school life. Even though schools use ‘student voice’, its meaning varied from school to school. In some schools it meant only gathering student views through surveys or focus groups while in other schools it meant setting up structures for students to participate in school decision making. The difference depended on how well the school promoted student leadership and students being in charge of their learning.

Students would also benefit from schools being more deliberate in promoting wellbeing in the curriculum. In many schools the only people who understood the overall curriculum and the competing demands on them were the students. What they experienced was very assessment driven and caused anxiety for many students. For example, schools could be more deliberate in their use of:

- the health and physical education learning area5

- key competencies6

- learning contexts in all learning areas

- leadership opportunities

- co-curricular activities – out-of-class activities that complement what students are learning in school.

An aligned and deliberate approach to wellbeing by secondary schools with a foundation of respectful relationships would support more adolescents to be “confident, connected, actively involved and lifelong learners.”7

Next steps

ERO recommends that the Ministry of Education provides examples of possible approaches to student wellbeing that are strongly aligned to the health and physical education learning area and supports the development of the key competencies.

ERO recommends that the Ministry of Education supports other relevant government agencies to ensure that programmes developed for schools align with the health and physical education learning area.

ERO recommends that the New Zealand Qualification Authority (NZQA) continues to work with school leaders and teachers to promote meaningful and innovative assessment practice that will deliver more manageable assessment programmes and a consequent reduction in teacher and student assessment workload.

ERO recommends schools:

- involve students in the review of and decision making about the approaches and actions that impact on their experiences at school

- review their senior school curriculum using The New Zealand Curriculum, in particular the key competencies, the health and physical education learning area and the senior secondary guidelines

- review their assessment programme, in particular the number of credits available for each year, using the intent of NCEA

- connect learning areas with sport and culture and leadership opportunities

- deliberately map and review the opportunities for students to explore wellbeing issues, and to develop and use key competencies and leadership skills

- engage parents and whānau in decisions that impact on the wellbeing of their young people.

Introduction

Adolescents want to test boundaries by exploring relationships with others to determine who they fit in with. They want to successfully navigate the risks that come with increased freedom and independence to determine which risks they are comfortable with, which cause harm and which lead to greater opportunities. They want their friends, family, teachers and other important adults to value and accept them, care for them and be trustworthy. They do this with much humour, creativity and panache.

Adolescents today have access to far more information, money and resources than any previous generation. Because of the internet and social networking, friends, bullies and marketers can influence young people’s thinking and actions far more than they could in the past. At the same time, New Zealand adolescents are becoming increasingly culturally eclectic as they borrow traditions from a range of cultural backgrounds. The boundaries of acceptable behaviour are not as clear as they were in the past and many parents feel they have less influence and wisdom to help their children navigate the complex issues they face.

Why a focus on student wellbeing?

The passage from childhood to adulthood is complex. It is a phase that is getting longer, with puberty starting earlier and full adult roles taken on in the mid-twenties or later. Most adolescents are resilient and thrive during this life phase. However, at least 20 percent of young New Zealanders exhibit behaviours or emotions or have experiences during this phase that can lead to long-term negative consequences.8

A focus on young people’s wellbeing has increased nationally9 and internationally.10 Although there is not a single measure for student wellbeing, the factors that contribute are interrelated and interdependent. For example, a student’s sense of achievement and success is increased by a sense of feeling safe and secure at school and, in turn, affects their resilience. By summarising findings from New Zealand12 and international papers, we know that:

- school factors influence student success

- many secondary-aged young people do not experience a high level of wellbeing.

ERO evaluated how well secondary schools promote and respond to student wellbeing. By understanding and improving this, it is hoped that all young people will experience a higher level of wellbeing during their adolescent years.

Background

In April 2012, Prime Minister John Key, launched the Youth Mental Health Project, with initiatives across a number of education and health agencies. The project aims to improve outcomes for young people aged 12-19 years with, or at risk of developing, mild to moderate mental health issues. The project has many initiatives. Over time, this project is expected to contribute to improvements in youth:

- mental health

- resilience and psychosocial wellbeing

- access to youth-friendly Health Care Services

- use of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs.

ERO’s contribution is an evaluation project to help schools promote and respond to student wellbeing. The evaluation is in four stages:

- Developing a set of evaluation indicators for student wellbeing for schools to use – Wellbeing for Success: Draft evaluation indicators for student wellbeing (draft) 2013 – in collaboration with health and wellbeing exerts and the education sector.

- Carrying out an evaluation of the provision of guidance and counselling in secondary schools.

- Carrying out national evaluations of how well primary and secondary schools promote student wellbeing. The evaluation findings are presented in this report and in the Wellbeing for Childrens’s Success at Primary School report.

- Publishing a national good practice report.

ERO will publish the evaluation indicators taking account of the good practice identified in schools.

What are the desired outcomes for student wellbeing?

Wellbeing is a concept that covers a range of diverse outcomes. All definitions of ‘wellbeing for success’ assume that young people are active participants in their learning and in developing healthy lifestyles. In developing the Wellbeing for Success: Draft Evaluation Indicators for Student Wellbeing (draft) 2013,13 ERO consulted with health professionals, young people, tangata whenua, school leaders and the wider education sector. The definition adopted represented these perspectives, and was central to Wellbeing for Success.

A student’s level of wellbeing at school is related to their satisfaction with life at school, their engagement with learning and their social-emotional behaviour. It is enhanced when evidence-informed practices are adopted by schools in partnership with families and the community. Optimal student wellbeing is a sustainable state, characterised by predominantly positive feelings and attitudes, positive relationships at school, resilience, self-optimism and a high level of satisfaction with learning experiences.14

On the basis of current research, ERO identified nine key ideas that demonstrated the Desired outcomes for student wellbeing. These are described in Figure 1.

Schools, through their own consulting processes, may have their own desired outcomes that reflect similar ideas.

Figure 1: Desired outcomes for student wellbeing

Students have a sense of belonging and connection to school, to whānau, to friends and the community

Students experience achievement and success

Students are resilient, have the capacity to bounce back

Students are socially and emotionally competent, are socially aware, have good relationship skills, are self-confident, are able to lead, self manage and are responsible decision-makers

Students are physically active and lead healthy lifestyles

Students are nurtured and cared for by teachers at school, have adults to turn to who grow their potential, celebrate their successes, discuss options and work through problems

Students feel safe and secure at school, relationships are valued and expectations are clear

Students are included, involved, engaged, invited to participate and make positive contributions

Students understand their place in the world, are confident in their identity and are optimistic about the future

The role of secondary schools

Secondary schools are important institutions for young people during adolescence. They provide guidance and role models for young people – as do other institutions, such as families and whānau, church groups and community groups.

Secondary schools provide young people with a complex framework for navigating choices that affect their lives, during and after their school years – such as what and how to learn, who to interact with, and how. These choices are made in the context of academic, co-curricular, leadership, qualifications, and vocational opportunities. During these opportunities students interact with teachers and their peers in a variety of ways – face-to-face or through electronic means, as an individual and as part of a group.

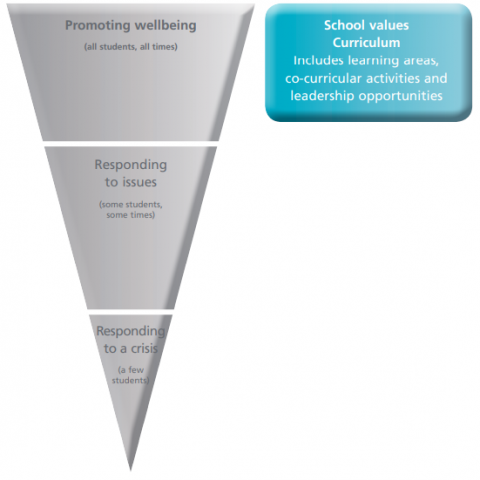

How secondary schools address student wellbeing can be understood by using a ‘promoting and responding triangle’,15 that describes the provision of support for all students (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Secondary schools’ promotion of and response to student wellbeing

The quality of these interactions determines whether each student feels there is at least one adult who cares for them and values them, who listens, who they can trust and who will support them through the decisions they make.

Responsibility for student wellbeing is described in documents that guide teacher actions. The Ministry of Education’s National Administration Guidelines16 states that each board of trustees is required to provide a safe physical and emotional environment for students; promote healthy food and nutrition for all students; and comply in full with any legislation currently in force or that may be developed to ensure the safety of students and employees. The New Zealand Teachers Council’s Code of Conduct17 for registered New Zealand teachers states that they will “promote the physical, emotional, social, intellectual and spiritual wellbeing of learners.” Their Registered Teacher Criteria18 state that fully registered teachers must “establish and maintain effective professional relationships focused on the learning and wellbeing of all ākonga”19 and “demonstrate commitment to promoting the wellbeing of all ākonga.”

Methodology

The overarching question for this national evaluation was:

To what extent do schools promote and respond to student wellbeing?

The evaluation involved 68 secondary schools in Term 1, 2014. The type of school, roll size and location (urban or rural) reviewed are shown in Appendix 1.

ERO’s judgement20 for each school was linked to ERO’s Wellbeing for Success: Draft Evaluation Indicators for Student Wellbeing (draft) 2013.21 The judgements were based on:

- the commitment and enactment of processes that promoted and responded to student wellbeing

- the inquiry processes that informed improved responses to wellbeing across the school, including processes for individual students with high wellbeing needs

- how well the learning, teaching and curriculum focused on improving wellbeing

- school leaders’ promotion of, and response to, student wellbeing

- the contribution to student wellbeing of school partnerships with parents and whānau, and with community health and social service providers.

Information used to make the judgement included:

- discussions with, and observing interactions among, students, parents and whānau, school leaders and teachers, guidance and counselling teachers, school social workers and nurses, and board members

- analysis of the school’s strategic documents, including plans for curriculum, professional learning and development (PLD), care for students, responses to traumatic events and minutes of meetings (especially about how the school used data about student wellbeing)

- analysis of Public Achievement Information (PAI), NCEA data, stand-downs, suspensions and exclusion data.

Individual students’ wellbeing could not be guaranteed in any school at any one time. Traumatic incidents, bullying and mental and physical health problems of students or significant members of their family or whānau affected an individual’s level of wellbeing, regardless of how focused a school was on student wellbeing. The important factors in making a judgement about each school were whether the school was prepared for such events and how evident the focus on student wellbeing was in the actions and documents associated with school culture, curriculum and systems.

Findings

This section explores the overall findings, the key characteristics of each group of schools, outcomes for students and what made a difference to how well schools promoted and responded to student wellbeing.

To what extent do schools promote and respond to student wellbeing?

ERO found that eleven of the 68 secondary schools sampled were well-placed to promote and respond to student wellbeing. These schools had systems that were cohesive and aligned with the school values. Although most students experienced high levels of wellbeing, there were still aspects that even these schools could improve on. Another 39 schools had elements of good practice that could be built on.

Eighteen secondary schools sampled had a range of major challenges that affected the way they promoted and responded to student wellbeing. Four of these schools were overwhelmed by their issues and unable to adequately promote student wellbeing.

What were the characteristics of each group of schools?

Schools that were well-placed to promote and respond to student wellbeing

Eleven of the 68 secondary schools were well-placed to promote and respond to student wellbeing. Well-placed schools were responsive to the individual learning needs of all students, indicated by high levels of achievement for most students and low levels of stand-downs, suspensions and exclusions. These schools had the least disparity between Māori and Pacific student achievement and that of other students in their school.

Well-placed schools differed from others in this evaluation by their:

- alignment of systems and partnerships with the values promoted in the school

- overall cohesiveness and the success of their initiatives in supporting students

- depth of inquiry and focus on improvement – this drew on a range of sources, including research and the perspectives of students, teachers and community.

In these schools “cohesion across policies, practices and initiatives contributed to an integrated and seamless approach to promoting student wellbeing”.22 These schools were working hard to support students to be “confident, connected, actively involved, and lifelong learners”.23

Students in these schools would benefit more if wellbeing outcomes were more explicit. Schools could:

- work more closely with students to understand their points of view and draw on their perspectives

- build a greater awareness of how well students were acquiring these wellbeing outcomes across the curriculum

- develop suitable initiatives and innovations to improve how well the school responds to students who need support to attain the wellbeing outcomes

- monitor students’ progress and evaluate the effectiveness of their approaches.

Schools where promotion of and response to student wellbeing was variable

ERO found 39 schools where wellbeing practices and approaches were variable within the school. Most of these schools were in urban locations. Schools in this group tended to have at least as good rates of NCEA achievement as their decile average for NCEA Level 1 and Level 2, but lower rates of students achieving Level 3. Māori and Pacific students tended to achieve at lower rates than their peers at all NCEA levels. Māori and Pacific students were also much more likely to be stood- down, suspended or excluded than their peers in these schools.

Schools with variable promotion of and response to student wellbeing generally had supportive care systems but had not focused any review on improving student wellbeing. Leaders were not able to say what was or was not working, or for whom.

These schools needed to:

- identify and extend good practices found in parts of the school

- recognise the need to promote wellbeing for success with a balance between academic and the other desired outcomes

- provide opportunities to develop genuine partnerships where teachers, students and parents actively contribute to decisions

- investigate how their own systems and practices may negatively affect students’ wellbeing, and make improvements to reduce students’ anxiety and stress

- investigate how they could adapt their systems to better align their values with what happens in practice.

Schools that were challenged in their promotion of and response to student wellbeing

The 14 schools that faced challenges in promoting and responding to student wellbeing had lower achievement at all three NCEA Levels than the previous two groups of schools. Māori achievement was generally much lower than other groups of students in these schools. Most of these schools also had high numbers of stand downs or suspensions, especially for Māori students.

The schools had diverse community backgrounds with varied wellbeing issues and priorities. Leaders in many of these schools recognised the need for a greater focus on wellbeing. Seven of the 14 schools had new principals who were working with teachers to improve identified areas of weakness, including:

- school culture

- relationships between teachers

- self review

- the school’s strategic focus on wellbeing.

Some schools were developing agreed school values and, with the support of new leaders, had renewed their focus on wellbeing. Some taught health well, especially for students in Years 7 to 10. Some schools had promising peer and academic mentoring processes. Many students in these schools enjoyed aspects of their time at school. These are all aspects that the schools can build on.

Students would benefit from:

- alignment between expressed values and practice

- better relationships and cooperation between teachers

- strengthening their care systems

- inquiry that focused on the affect approaches had on student wellbeing and made meaningful use of student views

- opportunities for students to develop key of The New Zealand Curriculum competencies and leadership skills.

Schools that were too overwhelmed to promote or respond to student wellbeing

Four schools were identified as overwhelmed and unable to adequately promote student wellbeing. All but one of these schools were rural. Some schools had high levels of poverty and social deprivation in the community and these surfaced as behavioural issues at school. They had mixed NCEA achievement profiles – with some achieving below other schools of a similar decile, while some were in line or above.

Some teachers had developed positive and supportive relationships with students but this was through their personal values and priorities rather than a consequence of a school culture that focused on positive relationships.

Students would benefit from high quality leadership to transform cultures in these schools.

What were the outcomes for students in the well-placed schools?

Students said adults treated them as inherently capable, despite any barriers or challenges they faced. They were responsible for many of their own school experiences, and accountable for how their actions affected others and themselves. Students knew they were expected to develop and use leadership skills. Opportunities were provided in academic, sports and cultural activities. Students emphasised how good it felt being spoken to by the teachers as ‘young adults’.

Most teachers ERO spoke with at well-placed schools understood the different needs of students from Years 9 and 10 to those in the senior school. They recognised that students had busy lives, and often had adult responsibilities outside of school. They knew that one of their roles was to guide and support students through the choices they made and that this guidance needed to change as students got older. Students ERO spoke with said they appreciated the support provided by teachers in their different roles, for example, classroom teacher, form/roopu teacher, dean, guidance counsellor or sports coordinator. Students who had suffered traumatic experiences said they had felt well-supported and cared for.

Even in these schools, students would benefit from wellbeing outcomes being made more explicit and having more opportunities to explore topical wellbeing issues at all year levels.

Promoting wellbeing

Secondary schools' promotion of and response to student wellbeing

Wellbeing was promoted through the way the school values were reflected in the quality of interactions (among students, teachers, parents and whānau, and the community) and through school curriculum opportunities: academic, co-curricular and leadership.

School values

Leaders in well-placed schools had systems to ensure that:

- students and their families and whānau identified with the school values

- the whole school community understood the values

- the values were embedded in day-to-day practice

- values were reviewed often to make sure they were relevant and practiced.

In these schools, values were consistently enacted and experienced. They helped students feel valued, included, supported and safe as shown in the example below.

School values are clearly identified in the school’s charter and are evident in posters around the school. They are well explained to students by leaders and teachers. Students’ behaviours that express the values are recognised and celebrated. Students confirmed they know the values and are expected to show them through their relationships with teachers and other students. They trust their peers and teachers. (A small school in a minor urban area)

Identifying values that are important to the school community

Values developed with in-depth consultation with the community reflected what was important to each school’s community. For example, integrated schools had values that reflected their religious faith and some boys’ schools focused on developing “Good Men”. Some schools used guidance from particular professional learning and development (PLD), for example Positive Behaviour for Learning24 (PB4L) or Te Kotahitanga,25 or particular theories such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs26 or Glasser’s theory of human behaviour,27 to identify values relevant to their context. The values contributed to students’ senses of belonging and connectedness to the school and the wider community.

Developing a shared understanding of the values

Leaders in many schools gave teachers and students opportunities to discuss the values and develop a shared understanding. Posters and notices reminded people about what was valued. At one school the values were explored in a Year 9 social studies unit. Students were clear about the importance of the values to the quality of their school experiences. Leaders had high expectations that the focus on positive relationships in the values would guide interactions among teachers and students.

Embedding values in day-to-day practice

Leaders in well-placed schools made sure the school values were a key part of day-to-day practice. The values guided the culture of the school and strongly influenced the aspirations of teachers and students. School values aligned well with practices and were used to guide planning. They could be seen in everyday activities and learning, at school events and through the development of a safe and positive environment for everyone. The following example illustrates how one school demonstrated cohesion between stated values and what was enacted.

The school’s values state that multiculturalism and inclusiveness are ‘unique and special ways’ for students to learn from one another. The school’s values were talked about in assemblies and in classrooms. Senior students talked confidently with ERO about the acceptance that existed for students of different ethnicities, cultures and religions. For example, the school had student-run support groups for sexuality education and gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) students. (A large urban secondary school)

Schools recognised and celebrated students who acted out the school values. Sometimes a school celebrated a particular student’s behaviour, but more often celebrated a large group’s behaviour at a particular event. This reinforced students’ understanding that these ways of behaving were the norm. Schools expected their student leaders to model the values. The example below shows how one school changed their student leaders’ expectations.

The role of the prefects has changed over recent years. Traditionally they were chosen based on their selection in elite sporting and cultural activities. Now prefects have to earn their position by role modelling and enacting the school values. (A large urban secondary school)

This careful and deliberate embedding of values meant that schools had caring relationships with students, their parents and whānau and the wider community. The culture was often described as ‘family-like’.

In other schools, ERO found that teachers did not always have the same beliefs about what the values meant. Little time had been spent making sure everyone understood what the values meant for relationships between students and teachers or how to ensure that the stated values were seen in practice. These schools often had their values written in strategic documents but school planning was not focused on improving student wellbeing. Curriculum or care issues and systems often did not match the expressed values. Some students knew the values, but did not consistently experience them.

In a few schools teachers and leaders were unsure what the school values were and so did not know how to promote and embed them in day-to-day practice. Teachers did not work together, had discordant relationships with senior management and some felt overworked and unsupported. These issues affected the relationships between teachers and students, and the school and its community – with real risks to student wellbeing.

Reviewing the relevance of the values and how they were put into practice

Effective leaders deliberately used a range of processes to review the relevance of the school values and to find out whether they were understood and used day-to-day. For example, teacher appraisal included reviewing values-in-practice in some schools. Students and teachers both contributed to the process in schools that undertook in depth reviews. In one school the students were also involved in the analysis stage.

A group of students was actively involved in the analysis and evaluation of data from the ’Wellbeing at School Survey’. Students joined teachers’ meetings to discuss the outcomes of the survey. Teachers found this approach enlightening and the students felt their views were listened to and valued. (A large urban secondary school)

Students, teachers and the board were all told the findings from reviews in schools well- placed to promote and respond to wellbeing. These schools responded quickly when the stated values differed from the experiences of students and their families and whānau.

Curriculum

Most teachers and leaders thought it was important for students to experience a range of academic, sporting and cultural opportunities. These opportunities helped develop student leadership, social skills and individual strengths and interests so that each student could be a ‘confident, connected, actively involved and life-long learner’.28 Students valued the opportunities offered.

“There are a wide range of cultural opportunities and chances to try new things. It doesn’t matter how good you are, you can all be good at something. We learn things so we can do them at our best”.

(Students at a medium sized, urban secondary school)

Leaders in well placed schools understood that this range of opportunities was the school curriculum. They had aligned systems to ensure curriculum opportunities:

- were designed to build on students’ strengths, interests and aspirations

- provided a range of options

- included ways to monitor student progress and wellbeing

- were frequently reviewed for relevance and adjusted to meet need.

Most schools did not connect the academic opportunities with the sporting and cultural opportunities and the care and guidance system. It was often left to each student to make sense of the connections and clashes.

Academic opportunities

Some schools were exploring ways they could deliberately support the development and use of key competencies across learning areas and through academic counselling. One way was by stating explicit key competencies in the planning and reporting for each learning area. This information was then captured in the school’s student management system along with other curriculum indicators. But not all of these schools had aligned key competencies across learning areas, so again it was left to students to make sense of the different messages.

The health and physical education teaching team provided much of the deliberate teaching and learning of wellbeing. Most schools allocated no more than two hours a week for health in Years 9 and 10. In the well-placed schools these programmes had effective teaching practices.

A junior school health programme was carefully planned to align with the principles of Hauora29 and the objectives of the health and physical education curriculum. Attention was given to social and emotional aspects of wellbeing such as identity, friendship, relationships, safety and bullying. Students talked about their wellbeing using the dimensions of Hauora. (A medium-sized urban secondary school)

Time for health programmes in Years 11 to 13 varied considerably. While some schools had strong senior programmes and one school had made health a compulsory component through to Year 13, others had more limited provision or no health programme for senior students. Students may not have had many opportunities to engage with topical wellbeing issues and ideas described in levels 6 to 8 of The New Zealand Curriculum.

Although not deliberately planned, students sometimes explored aspects of wellbeing pertinent to their lives in learning areas other than health. This was when teachers chose relevant and topical contexts. These explorations included themes in young people’s novels in English; themes about young people in different cultures or times in the arts, social sciences and media studies; social and environmental issues in science and technology; or health statistics in mathematics.

Schools need to be assured that all students have opportunities to explore wellbeing issues. They should map the teaching of these themes across learning areas and year levels to determine whether particular groups of students, because of the subject choices they make, had as many opportunities to explore wellbeing as other students.

Some schools provided one-off opportunities for senior students to explore wellbeing. At these ‘health promotion fairs’, a range of providers ran workshops and gave pamphlets to students. Most schools had not reviewed the impact of these days, which at best could provide some awareness of wellbeing issues.

Some schools provided an off-site event for a particular year group that was more in depth than a fair. A few schools developed programmes over a number of years so each opportunity built on the previous year’s experience. This is shown in the example below.

Boys explore wellbeing at senior annual retreats. Retreats are framed around religious themes/principles which are developed to address broad humanistic concerns. For example the Year 11 themes were “socialisation, defining justice, how to show mercy, personal attributes and qualities, temperaments, bonding as a group, liturgy and affirmation”. Retreats at Years 12 and 13 provide extensive opportunities for personal reflection, resilience building, positive self image building, affirmation and life planning. Teachers reported that issues of sexuality and sexual orientation are openly shared and discussed and that boys are open and accepting of their peers. Boys confirmed the value of the retreats, the empathetic nature of teachers involved and the deep personal learning that takes place, citing in particular the positive impact of the ‘affirmation’ process (statements in envelopes). (A medium-sized urban, secondary school)

Co-curricular activities

All schools valued students becoming well-rounded people. Most schools provided a large number of co-curricular activities for students to participate in. They recognised and celebrated diverse forms of success. Students spoke about the relationships they formed with teachers through these activities. As a result high levels of mutual respect were evident between students, and between teachers and students.

“We have more common ground with them. We know them outside the classroom, we appreciate their efforts”.

(Student at a medium sized, urban, secondary school)

In the well placed schools many initiatives or ‘clubs’ had been set up by students and were supported by teachers. This gave students the chance to lead initiatives.

Some students in other schools told ERO that they felt their interests were not supported by the school. Leaders may find that exploring school values through a wider range of co-curricular activities, particularly activities that can be student-led, will promote wellbeing for more students.

Leadership opportunities

Well-placed schools provided students with a range of leadership opportunities that contributed to their sense of wellbeing. These included:

- peer mentoring and buddy systems between older students and those new to the school such as tuakana-teina relationships30

- representing peers through school council processes

- designing classroom learning activities

- coaching sports and cultural groups

- leading interest groups

- representing the school at community forums.

Most schools provided leadership courses for particular groups of students such as school prefects, Pacific students, Māori students and sport coaches. Often these were one off events and for senior students. A few schools had designed ongoing programmes during a year. Many schools had used an external organisation to help with these programmes. As schools become familiar with and plan for key competencies, they will become more of aware of how the competencies support students to develop leadership skills. Schools need to consider whether all students have opportunities to develop and practise leadership skills otherwise there is the risk that it is always the same students who have the experiences.

In schools facing major challenges in promoting wellbeing, not all students felt valued or that teachers thought they were capable of making choices for themselves. This meant many did not respect teachers. At one school students identified issues in teachers’ self awareness and how they related to their students:

“They do not get to know us as people.”

(Students at a large urban secondary school)

In some classrooms in the challenged schools students got on well with their teachers and achieved well. However, the extent to which students could guide their own learning was limited. The schools lacked the high levels of trust needed for teachers to work closely with students to help them negotiate their learning and use their strengths to solve complex problems affecting them and/or their peers.

Pathways

Most schools provided a range of pathways within and from school. The quality of these pathways depended on the relationships teachers had with students and how well they monitored the students’ wellbeing. In well-placed schools these pathways met students’ needs and aspirations.

Pathways within schools provided students with accelerated or supplementary learning opportunities to ensure they experienced success. For example, one school noticed that students who took three years to complete NCEA level 2 needed extra support and developed a particular course for them. Another school created a class for a group of Year 10 boys who were not engaged or motivated with school.

Schools also designed pathways out of school for students that connected them to further study, employment or personal growth. One school had developed a support and tracking programme for a group of school leavers to make sure they successfully moved to employment or further study.

Monitoring wellbeing

Many schools had an academic counselling process that focused on goal setting, tracking and monitoring NCEA credits and developing pathways for leaving school. When this process was in line with the school’s values, it encouraged students to take responsibility for their own goals and pathways and promoted awareness of how they could manage themselves, their learning and their relationships with teachers and other students. Teachers and students indicated that this had helped to build relationships and enhance learning. Schools could extend this process to include tracking and monitoring of other goals associated with wellbeing. In the schools that did this, leaders and teachers understood that wellbeing included achievement priorities.

Not all schools were aware that all students should have a significant adult to go to, or knew whether all students at their school had someone. Students would benefit from school leaders finding out about students’ relationships with teachers.

Reviewing the approaches taken to promote wellbeing in curriculum

Schools reviewed their curriculum opportunities as part of their self review processes. The quality of self review varied. Opportunities for students to make decisions about their learning and school processes also varied, sometimes even within a school. In some schools, students reported that their suggestions had been acted on, but in other schools survey responses had not been analysed or used. Student opinions were gathered only through surveys in some schools. This meant that schools often had limited information on how well the curriculum was responding to their students.

Boards of trustees in well-placed schools had a culture of self review. They put a lot of effort into consulting particular groups of parents, family and whānau in ways they preferred, such as in small groups or at a marae. These boards supported the focus on student wellbeing by:

- appointing principals they thought could create an environment for all students to succeed

- developing a strategic plan in response to consultation processes such as funding Kaiawhina and Kaiwhahaere31 roles and Pacific achievement advisers

- providing resources for wellbeing approaches to meet the needs of priority students

- requesting and using reports about the effectiveness of the approaches.

In general, consultation about curriculum with parents, families and whānau and communities was quite limited. Schools consulted their communities about the content of sexuality education programmes but not about other aspects of the health curriculum or wider curriculum. This affected its overall quality.

Many schools did not have positive relationships with some groups in the community, which was a barrier to successful partnerships. Many students would benefit from schools improving their relationships with Māori whānau and Pacific families.

Being responsive to wellbeing needs

Secondary schools' promotion of and response to student wellbeing

This image is a reverse pyramid showing secondary schools promotion of and response to student wellbeing. From the top down it reads promoting wellbeing- all students, all times, responding to issues - some students some times, Responding to a crisis - a few students. Off to the side is two boxes which read having systems to notice and respond to issues. Examples include assessment overload and bullying. The next box reads having systems to notice and respond to individual high risk issues. Examples include self harm.

Schools noticed student wellbeing issues associated with:

- school values not being put into practice as expected

- a response to a certain aspect of the school curriculum

- high risk behaviour

- a student’s relationships with people close to them.

Schools had ways to follow up on these issues. Sometimes this required a preventative action for all students, to try and avoid anyone reaching the high-risk stage. In other cases specific interventions were needed for students with high-risk issues.

Leaders in well-placed schools had systems:

- that involved students inquiring into wellbeing issues

- to provide timely and appropriate responses

- to review the effectiveness of a response.

Inquiring into wellbeing issues

Most schools were looking into and addressing student wellbeing issues on a student by-student basis. In well placed schools, good quality care systems ensured that wellbeing issues were minimised, so that students’ ability to learn was not compromised. These schools tracked students’ engagement and progress, allowing them to identify wellbeing issues as they emerged and before they became more serious.

Most schools used regular meeting times with form/roopu teachers and dean/whānau leaders to discuss concerns about individual students. At one school leaders talked about the advantage for students when teachers connected academic and care information.

Departments compiled lists of students at risk: those not likely to achieve or not achieving due to non-attendance or non-completion, those who are not engaged as the course does not match their strengths or needs, or those with any other issue that puts them at risk. A faculty leader would contact the families of students on the list and deans use the list to identify any common concerns across departments. Faculty leaders underwent PLD on supporting students at risk. Teachers said the key to supporting students has been connecting and analysing academic and care information. Students have noticed the increased monitoring and interest from their teachers and one commented:

“It has helped me rise and help me achieve better in my struggling subjects.”

(A large urban secondary school)

Only a few schools were monitoring and responding to wellbeing concerns across a year group, such as patterns of non-attendance to classes or co-curricular practices, sick bay use or changes in friendship groups – even though many schools were capturing some of this information in their student management systems.

The well-placed schools had more than one way of gathering students’ perspectives. Some had started to include students’ opinions through surveys on issues like bullying.32 Leaders had also collected students’ opinions and ideas more directly by setting up specific focus groups and talking with school councils. Some schools were now seeking the perspectives of students because they had seen the benefits for enhancing the school culture and systems and in providing authentic contexts for students to develop their leadership and social skills.

Responding to wellbeing issues

In the well-placed schools, responses to antisocial behaviour, student truancy or lateness were consistent and restorative. School leaders saw this as a way for students to learn how to manage themselves and solve problems. Schools informed parents of any concerns about the students and invited them to help develop solutions. Although these schools did not claim to be ‘bully-free’, bullying was not seen by teachers or students as a significant issue. Teachers and students shared a sense of pride about focusing on positive relationships and not tolerating bullying at school or via the internet.

“It is a positive culture but we can have difficult conversations as well.”

(Principal at a medium sized, urban secondary school)

A key difference between schools that faced challenges in promoting and responding to student wellbeing and the well-placed schools was the reliance on outdated behavioural or disciplinary approaches rather than restorative practices. Many teachers viewed students as the problem and focused on ‘fixing’ their behaviour and blaming families without considering how they could instead develop a suitable learning culture. The less well supported students were often Māori students, those with difficult behaviours or students with special needs.

In some schools the stand-down and suspension rates of Māori students were higher than those of other students. Families and whānau were not involved with the schools and, in some cases, did not like what was happening at the school and did not want to be involved.

In two schools ERO found that section 27 of the Education Act33 was overused as an alternative to suspension. In a few schools there were higher than expected stand downs, suspensions and exclusions.

The high level of teacher dysfunction at a few schools made it extremely difficult to create a coordinated set of responses. The leadership in these schools had varying capacity to change the negative aspects of school’s culture or to drive improvement. The principals expressed a feeling of powerlessness in the face of the substantial changes needed.

Assessment anxiety

Many students experienced a very assessment driven curriculum, which caused them much stress and anxiety. Only a few schools recognised this and were responding to the detrimental effect on student wellbeing, especially in Years 11 to 15. A leader in one school responded to students who said they were stressed by exploring the number of NCEA assessments in each learning area across the year. They found that most students had two assessments every three days. After a discussion, leaders responded to this assessment overload by setting an expectation that subjects offered no more than 21 NCEA credits per course – even so, this could still lead to an unnecessary workload for students participating in six courses (126 credits when only 80 are needed). Leaders in another school were exploring the idea of more cross crediting between learning areas. In another school a number of traumatic incidents for individual students due to assessment anxiety led to a review of school culture and how teachers could reflect desired aspects of wellbeing.

The ‘a-ha moment’ was when the school realised that the emphasis placed on academic achievement was detrimental to their students’ wellbeing. The school noticed that a number of students, particularly in Year 12, were suffering from high levels of stress. Eating disorders had reached crisis point among a number of girls, and students were not getting enough sleep as they were studying through the night. The school recognised that while students were highly motivated and held extremely high expectations for success, this was negatively affecting their wellbeing.

Leaders gathered a range of information from students, their parents and other sources, and used this to re-think their approach to wellbeing. They implemented systems to monitor students and used ERO’s Draft Wellbeing Indicators as a guide for future changes to the school. They realised that while academic achievement and success was important to teachers and students, the school culture needed to model what ‘balanced’ meant as this was crucial to wellbeing.

To help students cope, the school realised that their curriculum needed to allow more time for balance and promoting wellbeing. The review led to a deliberate culture shift. The school now sends different messages through both informal and formal processes. For example, the countdown to NCEA assessments is no longer discussed at assemblies and instead is discussed when needed as part of an individual student’s academic counselling. (A large urban, secondary school)

Other schools had little understanding that their systems contributed to students’ stress and anxiety. Instead they blamed the stress on outside sources – on student, parental and community achievement expectations, and on New Zealand Qualifications Authority timings for assessments. This meant that school leaders did not recognise that they had the ability to reduce the stress on their students. In many of these schools teachers also talked about being stressed.

Students in all schools would benefit from leaders and teachers reviewing their academic curriculum and ensuring it is not assessment driven but instead reflects the principles and values of The New Zealand Curriculum and the senior secondary teaching and learning guides.34

Responding to high risk

In most schools students had access to counsellors and health professionals. Most schools had a range of successful partnerships in place with external health and social providers. But most schools did not have systems to identify and respond to the trends or issues that counsellors and health professionals faced, so did not know how to take preventative action. Not many schools had systems to provide ‘wrap- around support’ for students at risk. For these students, extending support from one-off meetings with the counsellor or health professional to across their curriculum experiences may be beneficial.

In some schools the guidance counsellors and nurses were overworked, as wellbeing responsibilities were delegated to a minority of adults and minimum time was allocated to the roles. For example, some Māori teachers carried a disproportionate burden where they were responsible for the care of all Māori students. In these schools the health and support services were less visible to students or more difficult to access.

In an earlier investigation into the provision of guidance and counselling,35 ERO found the guidance and counselling provision was serving students well in 30 of the 49 schools/ wharekura evaluated, with 14 of these doing very well. In the remaining 19 schools/ wharekura, guidance and counselling did not serve students well and, in four, ERO was concerned about the lack of guidance and counselling support for students.

A strong ethos of care existed in those schools/wharekura that were serving students well. The features of these schools/wharekura included:

- strong leadership

- strategic resourcing of people, time and space

- people with the professional capacity to help students manage their problems or refer them to expert help

- clear expectations around guidance and counselling practice.

Reviewing wellbeing responses

Leaders in well-placed schools had strategies in place to monitor the effectiveness of interventions. Boards and leadership teams scrutinised reports about the uptake and effectiveness of different approaches to wellbeing issues. While serious care issues could still arise, the systems in place meant teachers and leaders could respond to them efficiently and effectively.

Conclusion

Principals in schools that were well-placed to promote and respond to student wellbeing had systems to ensure school values, curriculum and responses to wellbeing issues were designed in consultation with the school community. They also made sure that these systems were adequately resourced to be a key part of day-to-day practice and were regularly reviewed to monitor their effectiveness. These leaders understood that students needed opportunities to:

- develop relationships with peers and adults that were based on mutual respect

- learn and take risks in a safe environment

- develop goals and experience success

- develop leadership skills and a sense of their own ability

- be “confident, connected, actively involved, and lifelong learners.”36

Students at these schools said they felt supported by teachers and that they valued being treated as resourceful young adults.

Even with this care, the key finding from this evaluation was that students in all schools were experiencing a very assessment driven curriculum and assessment anxiety. Achieving academic success is a part of wellbeing but is not the only factor. Very few schools were responding to this overload by reviewing and changing their curriculum and assessment practices. Schools need to explore the intent of NCEA and The New Zealand Curriculum (with the senior secondary guidelines) and develop a curriculum that is underpinned by the vision and principles of these documents.

Schools need to be assured that all students have opportunities to explore wellbeing issues. For most students, the health curriculum is only up to Year 10 and is no more than two hours a week. Schools need to map how wellbeing themes are taught across learning areas and year levels to determine whether all groups of students, because of the subject choices they make, have opportunities to explore wellbeing themes outlined in The New Zealand Curriculum.

Most schools, with their community, have developed a set of desired outcomes for students. By monitoring all of these outcomes, and not just achievement, schools would be better prepared to respond to the wellbeing needs of individual students and group of students.

In many secondary schools the only people who understood the school curriculum and care, and competing demands on them, were the students. Secondary students would benefit from their school leaders and teachers:

- involving students in reviewing and making decisions about the quality of their school experiences

- reviewing their curriculum using The New Zealand Curriculum, in particular the key competencies and the health and physical education learning area, and senior secondary guidelines

- reviewing their NCEA assessment programme

- connecting learning areas with sport, culture and leadership opportunities

- deliberately mapping and reviewing the opportunities for students to explore wellbeing issues, and develop and use key competencies and leadership skills

- engaging parents, family and whānau in decisions that affect the wellbeing of their young people

- finding solutions within the school community

- reviewing the effectiveness of actions by looking for patterns and trends.

ERO has made specific recommendations to the Ministry of Education, the New Zealand Qualifications Authority and to school leaders aimed at improving how well secondary schools promote and respond to wellbeing. These are outlined in Next steps on page 3 of this report.

Appendix 1: Schools in this evaluation

Twenty-three of these schools underwent an education review in Term 1, 2014. Due to the lower number of secondary schools having an education review in Term 1, an additional 50 secondary schools were invited to participate in the evaluation. Five of the schools declined to participate and were not replaced.

The type, location and roll size of the 68 schools involved in this evaluation are shown in Tables 1 to 3 below. The sample is representative of national figures for the location of schools. It is not representative of the national picture for types of school with students in Years 9 to 15, or in roll size.37 The sample includes a smaller proportion of small and very small schools (and a larger proportion of medium, large and very large schools) compared to the national proportions. Composite (Years 1 to 15) and Special Schools were underrepresented in the sample, and Secondary (Years 9 to 15) schools were overrepresented.

Table 1: School type

|

School type |

Number of schools in sample |

Percentage of schools in sample |

National percentage of secondary schools38 |

|

Composite (Years 1-15) |

4 |

6 |

20 |

|

Secondary (Years 7-15) |

18 |

26 |

22 |

|

Secondary (Years 9-15) |

45 |

66 |

50 |

|

Special School |

1 |

2 |

8 |

|

Total |

68 |

100 |

100 |

Table 2: Location of schools

|

Locality and population size |

Number of schools in sample |

Percentage of schools in sample47 |

National percentage of secondary schools |

|

Main urban (30,000+) |

39 |

57 |

61 |

|

Secondary urban (10,000-29,999) |

8 |

12 |

8 |

|

Minor urban (1000-9999) |

14 |

21 |

19 |

|

Rural (1-999) |

7 |

10 |

12 |

|

Total |

68 |

100 |

100 |

Table 3: Roll size

|

Roll size group (number of students) |

Number of schools in sample |

Percentage of schools in sample |

National percentage of secondary schools |

|

Very small (1-100) |

3 |

4 |

10 |

|

Small (101-400) |

13 |

19 |

31 |

|

Medium (401-800) |

23 |

34 |

28 |

|

Large (801-1500) |

21 |

31 |

22 |

|

Very Large (1501+) |

8 |

12 |

9 |

|

Total |

68 |

100 |

100 |

Appendix 2: Judgements used for the evaluation

To what extent does this school promote and respond to student wellbeing?

4 The school’s promotion and response to wellbeing is extensive

The school’s culture, values and operations are well aligned with those of ERO’s Wellbeing Indicator Framework39. The following features are evident:

- The school’s approach to student wellbeing, including values, leadership, partnerships and inquiry processes contribute to students attaining the Desired outcomes for student wellbeing (figure 1), particularly students with high wellbeing needs.

- There is a strong commitment and enactment of processes that promote and respond to student wellbeing, which align well with the Guiding principles for student wellbeing40 (or something equivalent) found in ERO’s Wellbeing Indicator Framework.

- Inquiry processes inform the development of improved responses to wellbeing across the school, including processes for individual students with high wellbeing needs.

- Learning, teaching and curriculum are focused on improving wellbeing. Wellbeing priorities are addressed through teaching and learning and this is integrated alongside (and complements) a school-wide focus on achievement.

- The principles of the health and physical education curriculum are evident across the school’s teaching and learning.

- Leaders are clear role models for promoting and responding to student wellbeing.

- School partnerships with parents and whānau, as well as community health and social providers, greatly contribute to the students attaining the Desired outcomes for student wellbeing.

3 The school’s promotion and response to wellbeing is good

The school’s promotion and response to student wellbeing reflects many of the aspects of the Wellbeing Indicator Framework, but there are areas where the school could improve. The following features are evident:

- Although there are several positive aspects to the school’s approach to wellbeing, gains could be made by a more strategic focus, such as the school bringing its work together in terms of the Guiding principles for student wellbeing (enhancing its collaboration and/or cohesion).

- The school’s culture is focused on promoting student wellbeing, and it has good care systems and initiatives, but its curriculum does not yet have a strong focus on wellbeing.

- There is some evidence that the school is contributing to many students attaining/working towards the Desired outcomes for student wellbeing.

- The school has some information on student wellbeing, which it responds to, but inquiry and improvement for wellbeing is not as coordinated or robust enough to consistently and systematically improve the school’s promotion of and responsiveness to student wellbeing.

- Some school partnerships make a contribution to student wellbeing, although there is potential for greater coordination between the school and health and social providers.

2 Some promotion and response to student wellbeing is evident

There are aspects where the school’s promotion and response to student wellbeing reflect the Wellbeing Indicator Framework, but there are several areas where the school could improve.

The following features are evident:

- The school has some good relationships, including those among many staff and students, but there some aspects of the school’s curriculum or care that do not yet support student wellbeing or engagement.

- Most of the school’s approach to wellbeing is delegated to a minority of staff.

- The school has some inquiry and improvement processes but does not consistently respond to the identified wellbeing priorities.

- There are many other forms of data the school should use to expand the scope of its inquiry into wellbeing, including student voice and involving whānau to identify wellbeing priorities.

1 Promotion and response to student wellbeing is limited

There are a few aspects where the school is promoting and responding to student wellbeing, but there are significant limitations overall. The following features are evident:

- The school has some staff who ‘care’, but overall, student wellbeing is not supported by significant elements of the culture, curriculum and systems of the school.

- The school has not clearly identified wellbeing priorities and/or there are few strategies or initiatives for change.

- Leadership for wellbeing lacks direction and commitment.

- Lack of partnerships act as a barrier to promoting and responding to student wellbeing.

- There is little to no engagement with inquiry and improvement processes connected to student wellbeing.

References

1. See Background, page 5.

2. These draft indicators were developed as part of the Youth Mental Health Project. They can be found on http://ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Wellbeing-Indicators-for-Schools. More details of the Youth Mental Health Project are found on http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/mental-health-and-addictions/youth-mental-health-project.

3. See ERO’s website www.ero.govt.nz National-Reports.

4. Often called restorative practices.

5. Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Page 22.

6. Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Page 12.

7. Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Page 37.

8. Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee. (2011). Improving the Transition: Reducing Social and Psychological Morbidity During Adolescence. Retrieved from www.pmcsa.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/Improving-the-Transition-report.pdf.

9. Ministry of Health. (2014). Youth Mental Health Project. Retrieved from www.health.govt.nz/our-work/mental-health-and-addictions/youth-mental-health-project.

10. See Goldin N. (2014) The Global Youth Wellbeing Index. A report of the CSIS Youth, Prosperity and Security Initiative and the International Youth Foundation. Retrieved from www.youthindex.org.

11. See Background in box, page 5.

12 For example see Ministry of Youth Development. (2014). Youth Statistics: Healthy. Retrieved from www.youthstats.myd.govt.nz/indicator/healthy/index.html.

13. Education Review Office. (2013). Wellbeing indicators for schools. Retrieved from www.ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Wellbeing-Indicators-for-Schools.

14. Noble, T., McGrath, H., Roffey, S. and Rowling, L. (2008) C. Canberra: Department of Education Page 30.

15. This framework has been modified from the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) Intervention Triangle as described in CASEL. (2008) Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) and Student Benefits: Implications for the Safe Schools/Healthy Students Core Elements. Washington DC: National Center for Mental Health Promotion and Youth Violence Prevention, Education Development Center. The Intervention Triangle is referred to in the Wellbeing for Success: Draft Evaluation Indicators for Student Wellbeing. Page 14.

16. Ministry of Education. (2013). National Administration Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/theMinistry/EducationInNewZealand/EducationLegislation/TheNationalAdministrationGuidelinesNAGs.aspx.

17. New Zealand Teachers Council. (2004) Code of Ethics for Registered Teachers. Retrieved from www.teacherscouncil.govt.nz/content/code-ethics-registered-teachers-1.

18. New Zealand Teachers Council. (2009). Registered Teacher Criteria. Retrieved from http://www.teacherscouncil. govt.nz/rtc.

19. The New Zealand Teachers Council uses ākonga to refer to all learners and students in the range of relevant education settings of New Zealand.

20. See Appendix 2: Judgements for the evaluation for a full description.

21. Education Review Office. (2013). Wellbeing Indicators for Schools. Retrieved from www.ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Wellbeing-Indicators-for-Schools.

22. Education Review Office. (2013). Wellbeing for Success: Draft Evaluation Indicators for Student Wellbeing. (Page 6). Retrieved from www.ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Wellbeing-Indicators-for-Schools.

23. Ministry of Education (2007) The New Zealand Curriculum for English-medium teaching and learning in years 1-13. Page 8.

24. Ministry of Education. (2014). Positive Behaviour for Learning. Retrieved from http://pb4l.tki.org.nz.

25. Ministry of Education. (2014). Te Kotahitanga: Making a difference in Māori education. Retrieved from http://tekotahitanga.tki.org.nz.

26. See A.H. Maslow Publications. (2014). Abraham H. Maslow: Books, Articles, Audio/Visual, & His Personal Papers. Retrieved from www.maslow.com.

27. See The William Glasser Institute. (2010). Glasser. Retrieved from www.wglasser.com/the-glasser-approach/choice-theory.

28. Ministry of Education (2007) The New Zealand Curriculum. Page 8.

29. Hauora is a Māori philosophy of health. It comprises taha tinana, taha hinengaro, taha whanau, and taha wairua. See Appendix B in Education Review Office. (2013). Wellbeing indicators for schools. Retrieved from www.ero.govt.nz/Review-Process/Frameworks-and-Evaluation-Indicators-for-ERO-Reviews/Wellbeing-Indicators-for-Schools.

30. This relationship is an integral part of traditional Māori society, and provides a model for buddy systems. An older or more expert tuakana (brother, sister or cousin) helps and guides a younger or less expert teina (originally a younger sibling or cousin of the same gender).

31. Māori students’ support or director roles.

32. Such as the surveys found on www.wellbeingatschool.org.nz.

33. Section 27 of The Education Act (1989) details the conditions under which a principal may exempt a student from attendance. See http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1989/0080/latest/DLM178252.html.

34. http://seniorsecondary.tki.org.nz.

35. Education Review Office. (2013). Improving Guidance and Counselling for Students in Secondary Schools (December 2013). Retrieved from www.ero.govt.nz/National-Reports/Improving-Guidance-and-Counselling-for-Students-in-Secondary-Schools-December-2013.

36. The vision for young people as stated in the Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Retrieved from http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/content/download/1108/11989/file/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum.pdf.

37. The differences in observed and expected values in Tables 1 to 4 were tested using a Chi square test. The level of statistical significance was p<0.05.

38. The national percentage of each school type is based on the total population of schools as at 30 July 2014.

38. Wellbeing for Success: Draft evaluation indicators for student wellbeing (draft) 2013. Pages 7-9.

39. Wellbeing for Success: Draft evaluation indicators for student wellbeing (draft) 2013. Page 6.

Publication Information and Copyright

Published 2015

© Crown copyright

Education Evaluation Reports

ISBN 978-0-478-43820-8

Except for the Education Review Office’s logo, this copyright work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to the Education Review Office and abide by the other licence terms. In your attribution, use the wording ‘Education Review Office’, not the Education Review Office logo or the New Zealand Government logo.