Summary

ERO is undertaking a series of evaluations on the implementation of Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. This report examines how prepared services are to implement Te Whāriki, including their engagement with professional learning and development, and determining 'what matters here' and next steps.

This report follows two evaluations ERO published in 2018: Awareness and confidence to work with Te Whāriki and Engaging with Te Whāriki. These earlier reports were a ‘temperature take’ of how leaders and kaiako in early learning services were beginning to work with the updated curriculum.

Whole article:

Preparedness to implement Te Whāriki (2017)Introduction

New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki, was updated in April 2017. Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa is for use by all early childhood education services: Te Whārikia te Kōhanga Reo is for use in all kōhanga reo affiliated to Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust.

Since July 2017 early learning services have been supported to implement Te Whāriki through a programme of professional learning and development (PLD) including workshops, webinars and online resources provided by the Ministry of Education (the Ministry). ERO is undertaking a series of evaluations on the implementation of Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa.

This report follows two evaluations ERO published in 2018: Awareness and confidence to work with Te Whāriki and Engaging with Te Whāriki (2017). These earlier reports were a ‘temperature take’ of how leaders and kaiako in early learning services were beginning to work with the updated curriculum. The reports focused on their awareness, familiarity and confidence with Te Whāriki, and their involvement in PLD to support them to start to implement the updated curriculum document. Figure 1 provides an overview of this series of evaluations and the focus of each phase.

Figure 1: ERO’s planned series of evaluations

Phase 1A: Awareness & confidence to work with Te Whāriki

Published July 2018

How is the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017) going?

- awareness of update

- accessibility/usefulness of PLD

- awareness of online information and other resources to support

- barriers and challenges to implementation.

Phase 1B: Engaging with Te Whāriki

Published November 2018

How is the implementation of Te Whāriki (2017) going?

- awareness of update

- accessibility/usefulness of PLD and resources

- how services are starting to think about reviewing and planning their local curriculum

- usefulness and use of learning outcomes

- barriers and challenges to implementation.

Phase 2: Preparedness to implement

This report

How well prepared are services to implement Te Whāriki (2017)?

- engagement in PLD

- steps being taken by leaders and kaiako to:

- decide ‘what matters here’

- review and design their local curriculum

- work with the learning outcomes to determine their priorities for children's learning

- determine their next steps.

- confidence to implement Te Whāriki.

Phase 3

How well are services implementing Te Whāriki (2017)?

- services focus on the learning that matters here

- parents and whānau are engaged in their child's learning

- children's identity, language and culture is affirmed

The updated Te Whāriki (2017) reflects changes in theory, practice and early learning contexts that have occurred over the last 20 years. Specific changes include:

- a stronger focus on bicultural practice, the importance of language, culture and identity and the inclusion of all children

- reviewing the learning outcomes and reducing them to 20 outcomes to enable a greater focus on “what matters here” when designing local curriculum

- setting out the links to The New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marāutanga o Aotearoa to support children’s transition pathways and learning continuity.

The aspiration for children, bicultural structure, principles, strands and goals remain the same. (Te Whāriki Online)

ERO’s Engaging with Te Whāriki report stated that “while there are no recipes or templates for implementation, there are some clear messages in Te Whāriki that convey expectations beyond those required by the prescribed curriculum framework.” These include:

- “That each service will use Te Whāriki as a basis for weaving with children, parents and whānau its own local curriculum of valued learning, taking into consideration also the aspirations and learning priorities of hapu, iwi and community”.(p.8)

- “That kaiako will work with colleagues, children, parents and whānau to unpack the strands, goals and learning outcomes, interpreting these and setting priorities for their particular ECE setting.” (p.23).

ERO’s previous evaluations regarding awareness and engaging with Te Whāriki have identified variability in the understanding and practice associated with implementing Te Whāriki, both within early childhood education services as well as between services.

This Phase 2 evaluation focuses on how well prepared leaders and kaiako in early learning services were to implement the updated curriculum.

By preparedness, we mean leaders and kaiako:

- engaging in PLD1 to build capability and a shared understanding of Te Whāriki and the implications of this updated curriculum for their practice

- implementing appraisal processes that support implementation

- reviewing their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki

- reviewing and designing their local curriculum to reflect the learning that is valued in their service

- identifying their next steps for implementation.2

The findings of this report are based on data gathered from 362 early learning services3 reviewed by ERO in Terms 2 and 3, 2018. Figure 2 shows how this data-gathering phase aligned with the timeline of Te Whāriki (2017).

Figure 2: Aligning ERO’s data collection with timeline of Te Whāriki (2017)

2016

- Development of Te Whāriki (2017)

April 2017

- Launch of Te Whāriki (2017)

July 2017-June 2018

- External professional learning and development:

- Webinars (ongoing)

- Workshops

- Te Whāriki Online (ongoing)

- Curriculum Champions

May-September 2018

- ERO’s data gathering for this phase

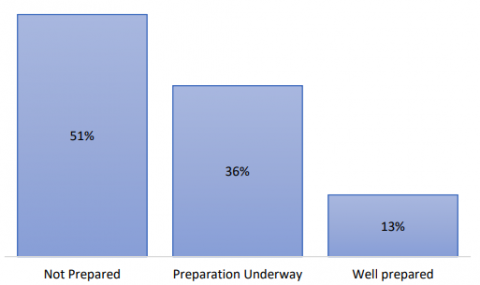

Over half of the services were not prepared to implement Te Whāriki

ERO is concerned that 51 percent of services were not prepared to implement Te Whāriki. Leaders and kaiako in these services had not yet taken steps to engage deeply with Te Whāriki.

ERO’s findings are summarised in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Half of services were not prepared to implement Te Whāriki (2017)

Figure 4: ERO’s key findings -preparedness to implement Te Whāriki (2017)

88%

- Leaders and/or kaiako in most services had been involved in some form of PLD (internal and/or external).

50%

- For half of the services, this PLD was limited and lacking the depth of engagement with Te Whāriki (2017) needed to understand the shifts required to effectively implement the updated curriculum.

55%

- In 55% of services leaders and kaiako had reviewed or taken some steps to begin to review their philosophy.

30%

- In almost one-third of services leaders and kaiako had taken steps to review and design their local curriculum. However the outcome of this process varied widely. ERO found differing approaches to thinking about a local curriculum and the extent to which it was consistent with Te Whāriki.

50%

- While half of the services had determined their priorities for children’s learning, the approaches to identifying (and the nature of) these priorities varied considerably. Few were considering the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki when deciding their priorities.

Insights for the sector

ERO recommends leaders and kaiako in early learning services use the findings of this report as a catalyst to:

- engage more deeply with Te Whāriki to build a shared understanding of expectations for reviewing and designing their local curriculum

- undertake more considered review and alignment of their philosophy with Te Whāriki

- unpack and discuss the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki and consider their impact on curriculum design, assessment, planning and evaluation processes

- evaluate their preparedness in implementing Te Whāriki and identify next steps and priorities

- engage in more collaborative internal and external PLD to strengthen understanding, practice, and pedagogy in implementing Te Whāriki.

External PLD needs to focus on working with learning outcomes and supporting leaders and kaiako to review and design their local curriculum.

ERO is currently revising its indicators for evaluating centre-based early childhood services. At the core of these indicators is the learner and their learning. The indicators have been developed to closely align to the learning outcomes and expectations set out in Te Whāriki.

Services’ preparedness to implement Te Whāriki

This section provides an overview of ERO’s key findings for ‘well-prepared’, ‘preparation-underway’, and ‘not-prepared’ services. It is based on the rubric used by ERO review teams to make an overall “best-fit” judgement about preparedness in the services evaluated (see Appendix 1).

Only a small percentage of services were well prepared to implement Te Whāriki

Services well prepared to implement Te Whāriki (2017) displayed the following characteristics:

Leaders and kaiako are engaged in PLD to build their capability to implement Te Whāriki-

Leaders and kaiako were engaging in a mix of externally-provided and internally-led PLD. This included attending workshops and accessing online webinars and resources. In many of these services leaders were accessing internal and external PLD to build their own capability to lead the implementation of Te Whāriki.

Through PLD, leaders and kaiako are building a shared understanding of Te Whāriki and they are clear about the implications of this updated curriculum for their practice - PLD was helping to build shared understandings and a sense of everyone ‘being on the same page’ with Te Whāriki. PLD was increasing the confidence of leaders and kaiako to work with Te Whāriki. It resulted in shifts in practice such as more intentional teaching, rich discussions about children’s learning, and increased reflection on practice.

Appraisal processes are supporting leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki- In most of these services, leaders and/or kaiako had appraisal goals linked to Te Whāriki. Some of these goals were more specific and explicit than others. In a few services, the goals provided a focus for kaiako to reflect more deeply on their teaching practice and outcomes for children.

Leaders and kaiako have reviewed their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki- These well-prepared services had recently reviewed their philosophy to align it with Te Whāriki. Most services had involved parents and whānau in the consultation process. The review of their philosophy was triggered by many factors including review of strategic and annual planning, and changes such as new team members, owners or leaders.

Leaders and kaiako have reviewed and designed their local curriculum to reflect the learning valued in their service (priorities for children’s learning) - In these services the concept of local curriculum was shifting from previous ways of planning to thinking about their priorities in relation to the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki and the aspirations of parents and whānau. Leaders and kaiako were able to talk about the factors influencing their local curriculum.

We still found variable understanding of what is meant by the concept of a ‘local curriculum’ even in these services, resulting in varied practices.

Similarly, we found varied understanding of the concept of priorities for children’s learning and what informs these priorities. The nature of the priorities also varied, ranging from very broad to specific for individual children.

Leaders and kaiako have identified their next steps for implementation in relation to Te Whāriki- These services were generally clear about the steps they needed to take to implement Te Whāriki. Steps largely focused on further PLD, engaging in ongoing internal evaluation around specific topics, or evaluating their implementation progress.

Just over one-third of services had begun to prepare to implement Te Whāriki

Leaders and kaiako with preparation underway had begun to take steps such as engaging in PLD, reviewing the service’s philosophy and/or identifying priorities for children’s learning. They were developing confidence in working with Te Whāriki. Some were in the early stages of engaging with PLD. Others were not engaging with Te Whāriki deeply enough to make the required shifts in the thinking and practice necessary to be well prepared to implement Te Whāriki. They were in the early stages of knowing about the impact of PLD, and needed to consider how to make more deliberate use of appraisal to support their implementation.

More than half of services were not prepared to implement Te Whāriki

ERO found a variety of factors that contributed to these services not being prepared to implement Te Whāriki. Common factors included the need for PLD for the whole team, or for further PLD that moved beyond awareness to deeper engagement with the expectations in the updated curriculum document. A lack of leadership and/or confidence to work with Te Whāriki was an issue for some of these services along with having more pressing priorities. Some of these services had experienced considerable staff change. One-fifth of these services had a change of owner, one-quarter had changes of manager, supervisor or head teacher, and nearly one-third had other staff changes.

Playcentres were more likely than other service types to be ‘not prepared’ to implement Te Whāriki.4 Of the 29 Playcentres in the sample, 23 were found to be not prepared. Issues for Playcentres reflected common factors for other ‘not-prepared’ services. However, restructuring at national and regional levels had also impacted on the quality of support available to individual Playcentres.5

The following provides an overview of ERO’s findings in the ‘not-prepared’ services based on ERO’s rubric.

In nearly half of the ‘not-prepared’ services leaders and kaiako are yet to engage in PLD to support them to implement Te Whāriki

Nearly half of these services had either not engaged in any PLD or PLD had been limited. Where engagement in PLD was limited, it was because the only PLD accessed was the Ministry-developed webinars and/or only leaders or some kaiako had engaged in the PLD. In the services that had engaged in PLD it was often limited to increasing familiarity with Te Whāriki and not going deeper into the curriculum intent.

In many ‘not-prepared’ services leaders and kaiako are yet to review their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki

Over half of these services had not taken any steps to review their philosophy to reflect the updated Te Whāriki. The remaining services had started to review their philosophy or had just reviewed it.

In most ‘not-prepared’ services leaders and kaiako are yet to review and design their local curriculum to reflect their priorities for children’s learning)

In just over three-quarters of these services, leaders and kaiako had not taken any steps to review and design their local curriculum. This was largely because they either did not understand the concept of a ‘local curriculum’ and/or had not realised this was something they needed to do.

Leaders and kaiako in most of the remaining services in this group had started work on their local curriculum, sometimes in a ‘business as usual’ way through planning for groups and individuals. For others, their local curriculum was very much driven by their philosophical approach.

In just over half of these services, leaders and kaiako had not yet taken steps to determine their priorities for children’s learning. Some had not yet considered doing this and others did not realise this was something they needed to do. Limited understanding of Te Whāriki coupled with a lack of knowledge about how to determine their priorities contributed to this.

In some ‘not-prepared’ services leaders and kaiako needed more support to identify their next steps for implementation of Te Whāriki

Although next steps had been identified in two-thirds of these services, in some the next steps were identified as part of the service’s ERO review. Common next steps to support the implementation of Te Whāriki included the need for further PLD and for ongoing internal evaluation to help teachers reflect more on Te Whāriki in practice and outcomes for children.

Some leaders and kaiako were not confident to implement Te Whāriki

We found varying levels of confidence in the services ‘not prepared’ to implement Te Whāriki. In some, leaders and kaiako were at an early stage of starting to engage more deeply and in others there were issues that limited confidence building. These were generally related to poor leadership, lack of time, lack of knowledge about the shifts in Te Whāriki, and a lack of engagement in any PLD.

Digging deeper into the findings

This section looks deeper into the information ERO collected from early learning services. It explores services’ involvement in and the impact of PLD, the use of appraisal, and the steps services have taken in reviewing and designing their local curriculum based on priorities for children’s learning.

Better use could be made of professional learning and development and appraisal to support leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki

Leaders and kaiako in 88 percent of the early learning services in this evaluation had accessed workshops, webinars, online guidance and resources. Some services had also used internal expertise and support from their governing organisation. There was wide variation in the impact of the PLD services had undertaken, and what they knew about the impact of the PLD across their services/teaching team. This also influenced how well services identified their PLD needs. ERO is concerned that in nearly half of the services that participated in PLD, engagement in PLD was limited; it did not include the whole team and/or the nature of the learning was very superficial.

Variable use of webinars, workshops and Curriculum Champions as effective PLD

About half of services had leaders and/or kaiako who had engaged with the webinars. Leaders and kaiako commented on the webinars being useful for:

- supporting access to PLD for services in isolated areas

- helping kaiako reflect on curriculum implementation, and deciding ‘what next?’

- growing knowledge of Te Whāriki

- supporting shared discussion among kaiako in some services.

Leaders and kaiako who did not find the webinars useful commented on:

- poor presentation

- basic or not relevant content

- a preference for face-to-face PLD.

Although half of the services had leaders and/or kaiako who had engaged with the webinars, in some services this had been left to individual kaiako. Subsequently, the learning from webinars was not shared among kaiako to promote deeper discussion about implications for practice which were pertinent to the service.

Almost half of services had leaders and/or kaiako attend Ministry-funded workshops. Leaders and kaiako appreciated that the workshops helped them understand the changes to the updated curriculum document. However, those who did not find the workshops useful felt they did not fit their service’s context, or did not make the changes in Te Whāriki clear. Leaders and kaiako in some services had difficulty accessing workshops due to a lack of space in sessions, or the workshops were not offered in their area.

Curriculum Champions were appointed as part of the Ministry’s PLD to support implementation of the revised Te Whāriki curriculum. The Curriculum Champions provided PLD to Pedagogical Leaders who were identified by their service to support leaders and kaiako to engage in curriculum inquiries. Few leaders and kaiako told ERO they used Curriculum Champions to support the implementation of Te Whāriki. Services where leaders and kaiako had used Curriculum Champions were most likely to be identified as “preparation underway”. In these services, leaders and kaiako were supported by Curriculum Champions to build knowledge about the Te Whāriki document, and how to use internal evaluation more effectively to consider how well they were implementing Te Whāriki.

PLD was having an impact in many services but not in all services or for all kaiako

ERO asked what leaders and kaiako knew about the impact of their PLD. Leaders and kaiako told ERO they recognised the impact of PLD from noticing changes in:

ERO asked what leaders and kaiako knew about the impact of their PLD. Leaders and kaiako told ERO they recognised the impact of PLD from noticing changes in:

- their daily professional conversations about children’s learning and the curriculum

- their teaching practices, such as intentional teaching, and the ways they were documenting

children’s learning

- the emphasis on learner voice in decision making.

In some services ERO found the impact of PLD was variable for a variety of reasons. These included:

- PLD targeted at a level of understanding not appropriate for the leader or kaiako

- only some staff attended PLD

- kaiako background and experience influenced their attitude towards PLD

- kaiako learning preferences influenced how well they engaged with the different PLD approaches such as online or face-to-face delivery.

Some kaiako and leaders recognised and addressed the variability of understanding in their services. They did this in different ways, including working with kaiako as a group (such as team meetings) to build capability to implement Te Whāriki, or working with individual kaiako to build their knowledge.

In services where PLD had a positive impact, leaders and kaiako told ERO this had resulted in:

- a greater understanding of assessment, planning and evaluation, including using the learning outcomes of Te Whāriki

- stronger internal-evaluation processes

- richer conversations and communication among kaiako, and between kaiako, parents and whānau about the curriculum and children’s learning

- increased understanding of bicultural curriculum and more culturally-responsive practices

- more deliberate, intentional, and purposeful teaching strategies after reflecting on practice.

One-third of services told us PLD had had no impact as they had:

- attended minimal PLD or none

- not seen any shifts in practice because of the PLD

- not found the PLD useful.

Nearly half of these services indicated it was too early to determine the impact of PLD. Some of these services did not have a clear process for evaluating the impact of PLD.

Well-prepared services were better at identifying what PLD they needed to do next

While over two-thirds of services had identified further professional learning needs to support the implementation of Te Whāriki, 28 percent had not. The well-prepared services and some of the preparation-underway services used a variety of ways to identify PLD needs.

Leaders and kaiako, and in some cases governing organisations, identified PLD needs in a variety of formal and informal ways including appraisals, strategic priorities, internal evaluation, and discussions with leaders.

The most common areas for further professional learning and development included:

- increasing understanding and awareness of the updated Te Whāriki

- integrating Te Whāriki into assessment, planning and evaluation

- strengthening curriculum in practice and pedagogy, including more emphasis on child-led and mana-enhancing practices, and addressing specific learning needs of children

- increasing bicultural and culturally-responsive practices

- exploring how to develop and implement a localised curriculum.

Some services lacked a clear process for identifying PLD needs, or appraisal systems were not fully implemented. In others, leaders and kaiako felt they had had limited access to initial external PLD and it was too early to identify their needs beyond wanting more external support. A few did not identify PLD as a need, as they believed Te Whāriki (2017) had few changes from the previous version.

Almost half of services were in the early stages of making deliberate use of appraisal

Almost half of services had started to link or intended to link appraisal for leaders and/or kaiako to Te Whāriki. In services making more deliberate use of appraisal, practices were already well established and effectively implemented. The use of Te Whāriki was considered an integrated part of the appraisal process. Leaders and kaiako had meaningful appraisal goals and inquiry processes that supported initial knowledge building about Te Whāriki and supported them to reflect more deeply on its implementation into practice.

A variety of factors were evident in services where limited use was being made of appraisal processes. Leaders and kaiako did not include Te Whāriki in appraisal because they were focused on other areas, or the service’s appraisal processes required development. Four percent of services in this evaluation sample were not meeting Teaching Council standards for appraisal.

Most services were not well prepared to review and design a local curriculum based on priorities for children’s learning

Review of philosophy and determining of priorities for children’s learning was variable

Almost a half of services had recently reviewed their philosophy with most aligning it to the updated Te Whāriki. Mostly leaders and kaiako undertook this review, with only half of these services involving parents and whānau in such review.6 Few services sought the views and perspectives of children or the wider community when reviewing their philosophy. Philosophy review was largely prompted by changes in the service such as change of owner, or changes to leadership and teaching teams. Other prompts included PLD, the update of Te Whāriki and engagement in planned internal evaluation. Philosophy review was underway in almost one-fifth of services, but still at an early stage in the process.

Over one-third of services had not taken any steps to review their philosophy. Changes such as owners or staff turnover meant it was not yet a priority in some of these services. In others, leaders and kaiako were waiting for PLD to help them to review their philosophy, or they were part of a governing organisation that took responsibility for the overarching philosophy. A few of these services had not reviewed their philosophy for some time.

While half of services had determined their priorities for children’s learning,7 the approaches to identifying, and the nature of, these priorities varied considerably. In most of these services, priorities were developed from the aspirations of parents and whānau, the intent of their philosophy, and the strengths and interests of individual children. In a few services priorities were pre-determined by the governing organisation. ERO is concerned that few services were considering the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki (2017) when deciding their priorities.

Fifteen percent of services were in the process of determining their priorities for children’s learning. A further one-third of the services had not taken any steps to determine their priorities. The lack of action in these services was due to one or more of the following factors:

- not knowing this was an expectation in Te Whāriki

- awaiting PLD to help them

- limited understanding about how to determine priorities and what to base these on yet to review their philosophy and/or update their strategic plan

- changes affecting the service including change of owner, leadership changes and/or staffing changes.

There was variable understanding about what is meant by ‘local curriculum’

Just over half of services had not taken any steps to review and design their local curriculum. In these services this was often because they either did not understand the concept of a ‘local curriculum’ and/or had not realised this was something that they needed to do. In some services there were staffing issues impacting on professional development and leadership, or they were waiting for the appointment of new staff before they could undertake these steps.

In the 30 percent of services where leaders and kaiako had taken steps to review and design their local curriculum, the outcome of this process varied widely. We found widely differing approaches to thinking about a local curriculum and in the extent to which it was consistent with Te Whāriki. Services with a specific educational philosophy, such as Montessori or Steiner, considered that to be their default local curriculum. In others, it was very much business as usual planning for children’s interests and strengths that didn’t show how kaiako and leaders were responding to the updated Te Whāriki. A few services showed deliberate consideration of the updated Te Whāriki as they developed their local curriculum.

Most services wanted further PLD but this needed to be more focused to make a difference

Eighty percent of the services had identified their next steps for supporting the implementation of Te Whāriki.

The most common next steps related to further PLD and internal evaluation. The focus of further PLD needed to be on:

- ongoing discussions in team meetings

- accessing the webinars

- support to review philosophy and determine priorities for children’s learning

- support for unqualified kaiako

- focusing on the use of learning outcomes in assessing children’s progress

- linking theory to practice.

Leaders and kaiako identified the need to undertake internal evaluation to:

- review aspects of practice related to teaching, planning and assessment

- identify further next steps for supporting the implementation of Te Whāriki

- review the service’s philosophy

- monitor and track improvements to teaching practice

- evaluate the service’s curriculum against Te Whāriki.

In the 20 percent of services that had not identified their next steps for implementing Te Whāriki (2017), it was because they were:

- waiting to participate in initial external PLD

- at a very early stage of engaging with Te Whāriki

- experiencing significant change in the service ownership, leadership or staffing coping with other issues, such as maintaining licensing requirements

- of the belief that not much had changed from the previous version of Te Whāriki

- of the view they were already implementing the updated curriculum.

Looking Forward

A commitment from government, along with leadership and expertise from the early childhood education sector, has helped shape this updated early childhood curriculum. The findings in this report highlight that to realise the potential of this commitment more consideration needs to be given to bringing it to life in all services for the benefit of all children. Leaders and kaiako must engage with the updated curriculum as education professionals with a responsibility for implementation.

This report has identified considerable variation in how well prepared leaders and kaiako are to implement Te Whāriki. This is concerning, as we know from an ERO synthesis on early childhood curriculum implementation that “variability in curriculum understanding and practice impacts on the extent to which children are provided with equitable opportunities to learn in meaningful contexts and through rich and challenging experiences.”

Te Whāriki (2017) sets a challenge when it states “the intention is this update will refresh and enrich early learning curriculum for future generations of children in Aotearoa” pg. 7. This statement indicates an expectation for change. To do this requires leaders and kaiako in early childhood services taking a deliberate and in-depth look at Te Whāriki and their own practices and local curriculum.

The findings highlight the need to strengthen opportunities for kaiako to engage more deeply with Te Whāriki, with an emphasis on strengthening practice and pedagogy. With appropriate support and guidance, leaders and kaiako need to seek and create these opportunities through their own professional learning and discussions, in addition to external PLD. Such learning opportunities need to address areas leaders and kaiako continue to find challenging. These include:

- leaders’ and kaiako understanding of the concept of reviewing and designing (weaving) their local curriculum based on decisions about ‘what learning matters here’

- assessing children’s progress and learning over time in relation to the 20 learning outcomes in Te Whāriki.

Leaders and kaiako need to have more shared discussions and collective critical reflection about Te Whāriki and what it means for their teaching, their service, their children and the way they engage with whānau. Te Whāriki (2017) states “kaiako are the key resource in any ECE service”p.59.

It emphasises the need for kaiako to work collaboratively with each other. This collective effort and responsibility is crucial to building in-depth professional knowledge of Te Whāriki and capability to provide a relevant, responsive and rich curriculum for all children.

ERO’s Engaging with Te Whāriki (2017) report identified that PLD on its own would not be enough to bring about improved understanding and practice. Strong pedagogical leadership was a

necessary factor in curriculum implementation. Leaders have a crucial role in promoting the structures and conditions for kaiako to be well prepared to implement Te Whāriki.

Leaders need to plan for, and be purposeful and deliberate in, the ways they support kaiako to implement Te Whāriki. This was a key feature that made a difference in the well-prepared services. The not–prepared services lacked this deliberate approach and the collaborative PLD to build leaders and kaiako knowledge about implementing Te Whāriki (2017).

This findings of this report also raise questions about the ongoing responsibility for monitoring and responding to how well the sector is implementing Te Whāriki. It highlights a need for educations agencies, PLD providers, and leaders and kaiako in services to identify what is working well and what needs to be improved to ensure the successful implementation of Te Whāriki.

It is particularly crucial to:

- evaluate the quality and effectiveness of PLD support

- identify how well services are implementing Te Whāriki and whether additional or different support is required to bring about the changes necessary so that all children experience the full promise of Te Whāriki (2017).

ERO is continuing to evaluate early learning services as leaders and kaiako implement Te Whāriki and will be reporting further on implementation of Te Whāriki in 2019.

ERO’s new quality framework and associated indicators of what matters most in early childhood services align closely to Te Whāriki (2017). From the beginning of 2020, ERO will be evaluating quality using this framework and indicators.

Appendix 1: Evaluation Rubric

A rubric was developed to define preparedness and was used to make an overall “best-fit” judgement about preparedness in each early learning service in the sample. The rubric was developed from the following information:

- expectations in Te Whāriki

- key messages in the webinars on Te Whāriki online

- key messages included in the resources and guidance material on Te Whāriki online.

Te Whāriki notes:

The expectation is that each ECE service will use Te Whāriki as a basis for weaving with children, parents and whānau its own local curriculum of valued learning, taking into consideration also the aspirations and learning priorities of hapu, iwi and community.(p.8)

The expectation is that kaiako will work with colleagues, children, parents and whānau to unpack the strands, goals and learning outcomes, interpreting these and setting priorities for their particular ECE setting. (p.23)

Planning involves deliberate decision making about priorities for learning that have been identified by the kaiako, parents and whānau and community of the ECE service. (p.65)

The online webinars and guidance information include some key messages about engaging with

Te Whāriki. Key messages in the webinars include:

- the role of leaders in ensuring there are systems and processes for:

- developing and reviewing the setting’s philosophy of teaching and learning

- considering kaiako interests, beliefs, skills, and knowledge in the provision of curriculum

- collecting and considering parent and whānau aspirations and wider community goals and concerns – including those of local iwi and/or hāpu

- Te Whāriki underpins your philosophy (not the other way around)

- making children’s learning visible in relation to collective priorities.

Questions guide the process of establishing and reviewing curriculum and learning priorities. Some examples include:

- How are the key ideas of Te Whāriki reflected in this setting’s curriculum?

- What is the learning that is valued in this setting? How are we ensuring that all children have fair and equitable opportunities to achieve this?

- How is this setting’s internal evaluation (self review) informing and responding to collective priorities?

- How are the collective priorities evident in planning and implementation?

Professional learning and development plays a key role in supporting leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki, particularly in relation to the areas the Ministry has identified as needing strengthening. Engagement in PLD helps build shared understanding and identify next steps for implementation, taking account of kaiako needs and the implications of Te Whāriki for the service’s policies, processes and practices.

Table 1: Rubric: preparedness to implement Te Whāriki

Not prepared

Leaders and kaiako have not engaged in PLD to support them to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako have not reviewed their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako are yet to review and design their local curriculum to reflect the learning that is valued in their service (priorities for children’s learning).

Leaders and kaiako have not identified their next steps for implementation in relation to Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako are not confident to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Preparation underway

Leaders and kaiako are just beginning to engage in PLD to build their capability to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Through PLD leaders and kaiako are starting to build a shared understanding of Te Whāriki (2017) and are considering the implications for their practice.

Leaders and kaiako have begun to:

- review their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki (2017)

- review and design their local curriculum so that it reflects the learning that is valued in their service (priorities for children’s learning)

- identify their next steps for implementation in relation to Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako are developing confidence to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Well prepared

Leaders and kaiako are engaged in PLD to build their capability to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Through PLD leaders and kaiako are building a shared understanding of Te Whāriki (2017) and they are clear about the implications of this updated curriculum for their practice.

Appraisal processes are supporting leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako have:

- reviewed their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki (2017)

- reviewed and designed their local curriculum to reflect the learning that is valued in their service (priorities for children’s learning)

- identified their next steps for implementation in relation to Te Whāriki (2017).

Leaders and kaiako are confident to implement Te Whāriki (2017).

Appendix 2: Evaluation process and questions

This evaluation involved ERO review teams making a judgement in each service about how well prepared leaders and kaiako were to implement Te Whāriki. We looked at the early impact of PLD in building capability and capacity of leaders and kaiako to review their philosophy, determine their priorities for children’s learning, and design their local curriculum.

The overall evaluation question is:

- How well prepared are early learning services to implement Te Whāriki (2017)?

In each early learning service ERO made a judgement about preparedness in relation to the following questions:

- How well prepared are leaders and kaiako in this service to implement Te Whāriki (2017)? (well prepared, preparation underway, not prepared)

- How confident are leaders and kaiako in this service to implement Te Whāriki (2017)? (very confident, somewhat confident, not confident)

In making this judgement review teams investigated and responded to the following questions:

- (a) How is PLD (internal and external) supporting leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki?

- How is PLD addressing the needs of leaders and kaiako within the service?

- What impact is PLD having?

- If the impact of PLD is variable, why is this so?

- How are appraisal processes helping leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki?

- (a) What steps are leaders and kaiako taking to review their service’s philosophy to align it to Te Whāriki?

- What steps are leaders and kaiako taking to determine their priorities for children’s learning?

- What steps are leaders and kaiako taking to review and design their local curriculum to reflect these priorities?

- What steps are leaders and kaiako taking to identify their next steps for implementation?

- How well prepared are leaders and kaiako in this service to implement Te Whāriki (2017)? (well prepared, preparation underway, not prepared)

- How confident are leaders and kaiako to implement Te Whāriki in their service?

(very confident, somewhat confident, not confident)

Appendix 3: Sample of early learning services

Table 1: Service type

|

Service Type |

Number of services in sample |

Percentage of services in sample |

National percentage of services8 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Casual Education and Care |

1 |

<1% |

<1% |

|

Education and Care |

237 |

65% |

62% |

|

Playcentre |

29 |

8% |

10% |

|

Kindergarten |

54 |

15% |

16% |

|

Home-based Education and Care |

40 |

11% |

12% |

|

Hospital-based Education and Care |

1 |

<1% |

<1% |

|

Total |

362 |

100% |

100% |

As shown in Table 1, this sample was representative of national figures.9

Table 2: Location

|

Location10 |

Number of services in sample |

Percentage of services in sample |

National percentage of services |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Main Urban |

261 |

72% |

75% |

|

Secondary Urban |

20 |

6% |

6% |

|

Minor Urban |

45 |

10% |

11% |

|

Rural |

36 |

10% |

8% |

|

Total |

362 |

100% |

100% |

As shown in Table 2, this sample was closely representative of national figures.

Appendix 4: Characteristics of services and preparedness

Table 1: Characteristics of the 45 well-prepared services

|

Service type |

# |

Ownership |

# |

Change factors |

# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education and Care |

27 (of 237)11 |

Private |

25 (of 201) |

None |

32 (of 176)12 |

|

Kindergarten |

10 (of 54) |

Community |

20 (of 161) |

Staff |

8 (of 95) |

|

Home-based Education and Care |

7 (of 40) |

|

|

Leadership |

10 (of 108) |

|

Casual Education and Care |

1 (of 1) |

|

|

Ownership |

1 (of 51) |

Other factors

Six were having their first ERO review and 20 services were part of a governing organisation.13

Table 2: Characteristics of the 131 preparation-underway services

|

Service type |

# |

Ownership |

# |

Change factors |

# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education and Care |

93 (of 237) |

Private |

65 (of 201) |

None |

55 (of 176) |

|

Kindergarten |

23 (of 54) |

Community |

66 (of 161) |

Staff |

32 (of 95) |

|

Home-based Education and Care |

9 (of 40) |

|

|

Leadership |

43 (of 108) |

|

Playcentre |

6 (of 29) |

|

|

Ownership |

15 (of 51) |

Other

Six were having their first ERO review and 49 services were part of a governing organisation.

Table 3: Characteristics of the 186 not-prepared services

|

Service type |

# |

Ownership |

# |

Change factors |

# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education and Care |

117 (of 237) |

Private |

111 (of 201) |

None |

89 (of 176) |

|

Home-based Education and Care |

24 (of 40) |

Community |

75 (of 161) |

Staff |

55 (of 95) |

|

Playcentre |

23 (of 29) |

|

|

Leadership |

55 (of 108) |

|

Kindergarten |

21 (of 54) |

|

|

Ownership |

35 (of 51) |

|

Hospital-based Education and Care |

1 (of 1) |

|

|

|

|

Other factors

Eighteen were having their first ERO review and 78 services were part of a governing organisation.

Citations

1 Professional learning and development includes professional learning opportunities provided by and occurring within the service, and from external sources.

2 See Appendices 1 and 2 for the evaluation questions and rubric used to make a judgement about preparedness.

3 See Appendix 3 for the sample characteristics. Please note the sample does not include Kōhanga Reo.

4 Differences in ratings between service types were checked for statistical significance using a Kruskal-Wallis H test. Playcentres were less well prepared than other service types to implement Te Whāriki. The level of statistical significance for all statistical tests in this report was p<0.05.

5 See Appendix 4 for the characteristics of services in the three preparedness categories.

6 This will be a focus in subsequent evaluations.

7 This reflects ERO’s findings in its 2013 report, Priorities for Children’s Learning in Early Childhood Services.

8 National percentage of services as at 30 November 2018.

9 The differences between observed and expected values in Tables 1 and 2 were tested using a Chi square test.

10 Main urban areas have a population greater than 30,000; secondary urban areas have a population between 10,000 and 29,999; minor urban areas have a population between 1000 and 9,999; and rural areas have a population less than 1000.

11 I.e. 27 of the 237 education and care services in the total sample were well prepared.

12 I.e. 176 services in the total sample had no change factors, and of these 32 were well prepared.

13 Governing organisations include kindergarten and playcentre associations and organisations with oversight of 30 or more services.