Summary

There are a small number of schools in New Zealand that are failing to provide students with equitable access to high-quality learning experiences. Students within these schools are not achieving expected academic outcomes.

Despite longitudinal reviews by the Education Review Office (ERO) and support from the Ministry of Education (The Ministry), some of these schools continue to make limited progress or may experience further decline. The ERO and the Ministry identified the need for a different approach.

The Turnaround Schools (TAS) pilot was a national project initiated in 2017. The purpose was to trial and implement an approach to support schools experiencing ongoing performance challenges. The pilot was underpinned by a commitment to a collaborative, multi-agency approach to school improvement.

A group of experienced reviewers within ERO - under the guidance of a national project manager - were appointed as a specialist review team. The team developed an intensive monitoring and evaluation approach to interrupt school decline. Their focus was to use evaluation evidence to identify performance challenges, catalyse action, and promote school turnaround.

Six schools were selected to participate in the pilot. All schools were Tier 1 schools classified as repeatedly poorly performing and/or schools in rapid decline. All schools have a high proportion of Māori students, and/or students who identify as being of pacific ancestry.

An external evaluation was commissioned early in 2020. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the effectiveness of the TAS pilot as a strategy for school improvement. While the partnership with the Ministry was a critical element of the approach, the external evaluation focused on the core components of ERO’s work with schools.

The objectives of the evaluation were to:

- document stakeholders’ perspectives on the implementation of the pilot approach,

- assess the effectiveness of the pilot approach in supporting schools to progress improvements, and

- identify learnings to inform further work with persistently low performing schools

The evaluation documented perspectives of key stakeholders in the six schools, and representatives within ERO and in the Ministry. Additional quantitative data was reviewed to explore the trajectory of changes in student outcomes from baseline to 2019.

Whole article:

Evaluation of the Turnaround Schools (TAS) Pilot ProgramKey findings from the external evaluation

Overall Implementation Processes

- Stakeholders consulted in this evaluation noted a range of differences in the underpinning philosophy and activities of the TAS pilot from ERO 1-2 reviews. The major points of demarcation included

- the pilot’s emphasis on the development of a collaborative working relationship with schools, with the Ministry and NZSTA,

- the focus on using monitoring and evaluation for school improvement rather than primarily for accountability, and

- use of the TAS reports produced each term for advocacy for additional support or resourcing

- A collaborative platform was established from the design and inception of the pilot, but the way that communication occurred between agencies was sometimes patchy. The evaluation found evidence that the levels of collaboration between ERO and the Ministry improved over time.

- Ministry of Education representatives expressed support for the work of the TAS team in the schools. The term by term reviews mobilised action by the schools to address performance issues.

- ERO Directors from the three regions acknowledged the importance of working closely with the schools. However, one of the directors suggested that the pilot was overly-ambitious and questioned the focus on school evaluation as the key mechanism for school improvement.

- Directors indicated that strategic communication about the progress of the pilot did not always occur within ERO, which made it difficult to assess how the pilot or the schools were progressing.

Implementation at the School level

- The evaluation found evidence that the team were effective in working in partnership with the schools. The relational approach, and the continuity of the team anchor in each school appeared to be important in supporting critical reflection.

- Regular contact with the schools enabled reviewers to gain a deeper knowledge of the school context over time. Demonstrated understanding of context appeared to positively influence the level of professional trust between reviewers and the schools.

- It was evident that the match of particular reviewer skillsets to school needs was an important consideration. The skills of the reviewers and their fit to the school enhanced professional trust and supported respectful practice. A clear example of this was drawing on the knowledge, leadership and skills of Māori colleagues to facilitate connections and conversations within schools. Two school stakeholders also spoke of the translational skills of Māori reviewers in the TAS team. These reviewers assisted them in understanding the issues identified in TAS reports. Pākehā reviewers in the team valued the opportunity to work with Māori colleagues. They believed that co-working positively influenced their own cultural understandings and were a rich source of professional learning.

- Review reports validated the perspectives of school stakeholders, and generally were considered accurate reflections of the issues that needed to be addressed. However, there was a view there was a mis-alignment between verbal and written reports on some occasions. Where this had occurred principals were able to voice their concerns, and modifications were made -if appropriate - to the written report.

- School stakeholders perceived a tension between the team’s role as evaluators vis a vis provision of support and advice. Most of the stakeholders interviewed suggested it was a lost opportunity for influence with schools if ERO maintained an exclusive focus on monitoring and evaluation.

- Over the three years of the pilot the TAS team developed a range of resources to support schools to sequence actions for improvement. The School Evaluation Indicators (ERO, 2016) were elaborated to ‘unpack’ progressions for schools classified at the lower end of the rubric. Qualitative radars were developed to map progress on a range of dimensions from review observations and data collection. These tools may be useful as progress markers for other evaluation work undertaken by ERO with schools.

Outcomes

- Evaluation evidence indicated that the TAS pilot was effective in accelerating improvements within five of the six schools. Organisational dynamics, including the commitment and readiness of leaders within each school influenced the rate and pace of change. It is likely that the context of the school and its relationship with the wider community will also influence the sustainability of improvements.

- Identified improvements within the schools were not solely attributed to the pilot. A range of support initiatives had been put in place within these schools during the pilot timeframe. The cumulative value of the initiatives by ERO, the Ministry and NZSTA had created the conditions necessary for improvements to occur.

- School stakeholders considered the pilot was of value to the school. The average rating of the value of the pilot to school improvement was 4 out of a possible 5.

- School stakeholders (principals and board chairs) indicated that the review and reports each term had created an urgency to respond. While in most cases the reports were seen as accurate reflections of the school, school stakeholders expressed feeling overwhelmed by the number of issues they were required to address in the termly reports.

- There is evidence that the TAS pilot has strengthened knowledge about ways schools can use data to assess progress. While most school stakeholders viewed this positively, two of the principals reported that the ‘relentless’ focus on particular kinds of data was a distraction from tailored activities they were developing and/or trialling to improve student engagement and learning.

- Ministry stakeholders highlighted the value of the TAS reports in identifying additional resourcing and support needs within schools. The reports provided a robust evidence base. In most cases it appears that the Ministry was able to use the reports to expedite support to schools.

An overview of quantitative and qualitative changes in schools from baseline to 2019 is presented in Table 1. This report focuses on stakeholder feedback about the role of the pilot in contributing to school improvement.

Table 1: Summary of Pilot school improvements

|

School |

School-level changes – Quantitative outcome data since baseline (2016-2019) |

Improvements - Qualitative |

|---|---|---|

|

School 1

|

- Improvement in NCEA Level 3. - NCEA Level 2 is solid with those students improving from Level 1. This is where the school has put their focus. - Growth in community connections and leadership |

- Whānau structures developed to support learning -Teacher capability has increased in the school - Implementation of curriculum modules to promote engagement and literacy, and enhance vocational/academic aspirations |

|

School 2

|

-No formal quantitative data available. Note: In 2020 it was recommended that a Commissioner be appointed to this school as the school had not demonstrated sufficient improvement |

-Local curriculum focus on local Schooltanga and community tanga in learning design -Schoolwide focus on student wellbeing |

|

School 3

|

-Years 7 to 8 and Years 9 to 10 classes are receiving more appropriate teaching programmes focused at their level of learning.

- Teacher capability in math and evidence of improvements in mathematics |

- Distributed leadership model promoted consistency in strategic communication within the school, and may support sustainability - School and board interest in using data and enhancing evaluative thinking - Whole school numeracy focus |

|

School 4

|

- Improvement NCEA Level 1, 2 and 3 - Marked improvement in NCEA Level 1 2017 to 2018. (At least 100 students at Years 11, 12 and 13) - Reduced disparity to national decile band data for each level - School roll is steadily increasing |

- Strengthened leadership capability of Senior Leadership team and Heads of Faculty - Improved school systems, particularly in data monitoring and tracking. - Re-invigorated board with growing capability in governance - Rigorous curriculum Review-Improved range of pathways for students |

|

School 5 |

- Improvement NCEA Level 1 and 2. Stable Level 3. The school is now close to decile average. - By the end of 2019 more students were completing external NCEA standard - Leavers with at least NCEA Level 1 has steadily increased (however, still below national and decile 1) - School roll is growing rapidly |

- Significant shift in school culture and community engagement - Whānaungatanga - positive changes in school climate and evidence of strong student voice within the school - The newly appointed board chair has a strong focus on performance measurement |

|

School 6

|

-Improved NCEA Level 1 Literacy/Numeracy

|

-Local curriculum development is progressing -Staff capabilities in te reo Māori, maths and literacy -Whānaungatanga/positive school climate |

Opportunities for Improvement

Stakeholders identified opportunities for improvement of the pilot approach that – from their perspective – would have made the pilot more effective. Five key actions were identified from a thematic analysis of feedback. They were:

- Clarify roles and responsibilities and provide ongoing communication mechanisms to ensure all stakeholders are clear about purpose, scope and role differentiation.

- Improve the alignment between verbal and written reports.

- Build on the collaborative platform with schools and include opportunities for co-construction of reports.

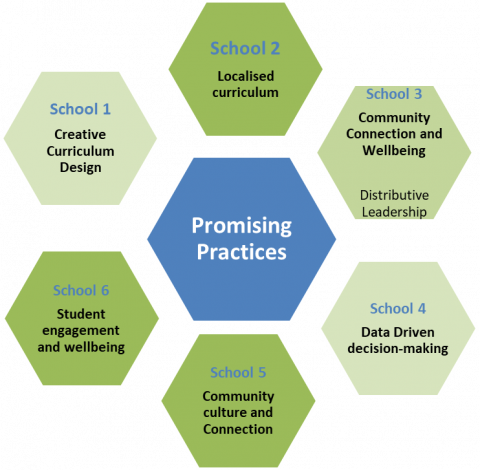

- Actively share promising practices about what works for school improvement with the schools to increase their knowledge and learning, and reduce duplication of effort, and

- Sharpen criteria for evaluation of progress and exit of schools from intensive monitoring and review.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are intended for consideration by ERO. They relate to the strategic and structural elements of school evaluation approaches for schools experiencing persistent performance challenges.

- It is recommended that ERO maintain a dedicated group of experienced evaluators to focus on schools with persistent performance challenges. The extension of the pilot to a greater number of schools through the High Priority Schools (HPS) approach in 2020 is formal recognition by ERO of the importance of this work. However, the continuation of the pilot level of resourcing (time and scope of work with schools) is likely to be unsustainable as work is extended to a greater number of schools. ERO will need to identify strategies to balance internal resource constraints with their capacity to influence change.

- It is recommended that the TAS team’s role be extended to provide additional support and/or PLD in monitoring, evaluation and using data for improvement purposes. The team has developed a sound knowledge base about what works with Turnaround schools within the NZ context, and this information will continue to be useful for ERO, the Ministry and for schools.

- It is recommended that the learnings from the TAS pilot be used by ERO and the Ministry to inform the work undertaken to shift performance in other underperforming schools.

- It is recommended that schools – principals and potentially board chairs - be provided with an opportunity to share lessons learned, and to highlight promising practices that support school improvement. The success case profiles in this report highlight some topics that potentially could be explored and elaborated. Principals in the six schools indicated they would welcome an opportunity to share experiences. A joint forum with ERO and the Ministry would also provide a further opportunity for learning about useful strategies that have worked in similar school contexts.

- It is recommended that the tools and resources developed over the past three years by the TAS team be shared more widely across ERO and the Ministry. Additional work may be required to provide guidance on the use of each tool, and the purpose and process of use with schools to ensure they are used appropriately and with fidelity. Some of these tools (e.g., the school radars) may be particularly useful in bringing together qualitative assessments and judgements of the review team, with quantitative school outcome data.

- It is recommended that evaluation mechanisms are built into school improvement approaches to allow for progressive formative feedback. The explicit inclusion of process evaluation within any school improvement approach also has the benefit of demonstrating that ERO and the Ministry ‘walk the talk’ of evaluation for improvement and learning.

- It is recommended that a simple map of the improvement phases be developed to increase school and board understanding of progress markers for withdrawal or ‘dial-down’ of the intensity of engagement with ERO.

Structure of the Report

The report is divided into five sections.

Section 1 provides a brief overview of the policy context and rationale for the Turnaround Schools Pilot Approach.

Section 2 summarises the purpose and methodological approach adopted in this external evaluation. An evaluation data matrix presents the sources of evidence and evaluation methods. Additional detail about the evaluation methods and analytic processes is included in the accompanying appendix.

Section 3 provides an overview of the objectives of the pilot and describes the major components. This section also presents a programme logic map developed during the evaluation, which describes the ‘pilot on a page.’ It summarises policy drivers, key phases and pilot activities in schools and aligns these to intended outcomes. This section also provides a brief description of each of the schools in the pilot, the implementation activities, and stakeholders’ initial responses.

Section 4 is the main section of the report. It presents detailed findings about stakeholders’ views of the pilot and the way it worked, and key elements of effectiveness. The three core outcome domains that were examined in the external evaluation were:

- Schools have an enhanced capacity to gather and use data for planning,

- Schools find the TAS reports useful for planning for improvement, and

- Schools have necessary supports in place to progress planned improvements

Promising practices identified by school stakeholders or ERO reviewers working with the schools are highlighted in this section of the report. The presentation is explicitly strengths-based. The section also outlines opportunities for improvement.

Section 5 summarises the lessons learned, key implications and recommendations emerging from a synthesis of evaluation findings.

Section 1: Introduction and background

All young people within New Zealand deserve access to a quality educational experience. A key role for schools is to provide the environment and conditions to support students to develop skills that will prepare them for further study or work. Schools also play an important role in supporting the social and emotional wellbeing of students.

However, a small percentage of schools within New Zealand are failing to provide students with equitable access to high quality learning experiences and students are not achieving expected outcomes. These schools, invariably are located in Decile 1-3 areas and have a high proportion of students who identify as Māori or with Pacific ancestry[1]. The continued poor performance of these schools widens the gap in achievement and threatens equitable outcomes for all New Zealanders.

In 2011, ERO developed a differentiated review methodology that focused reviews to school context, performance and evaluation capacity. While most schools were subject to reviews every three to five years, some schools were identified as requiring a more regular review every one to two years.

The schools classified as Repeatedly Poorly Performing (RPPS) often demonstrated poor performance in five areas (which correspond to the 2016 School evaluation indicators). The areas were:

- Equity and excellence of student achievement outcomes

- Other valued student outcomes including student engagement and wellbeing

- The quality of teaching and curriculum design and opportunities to learn

- Professional leadership

- Stewardship – notably the cycle of planning reporting and resourcing, and/or health and safety

The Ministry and ERO work together to evaluate the quality of education from a common framework to enhance student outcomes.

The Education Review Office (ERO) independently conducts reviews of schools for learning, school improvement and accountability. Poorly performing schools are primarily identified through ERO’s evaluations. Schools that are experiencing performance challenges and low student achievement outcomes are placed on a longitudinal review process. While ERO conducts a review of these schools every one to two years, ERO is not responsible for managing the performance of schools.

The Ministry of Education also has mechanisms to identify schools that are poorly performing or at risk of poor performance. Regional advisors within the Ministry monitor school performance through annual reports provided by the school on academic achievement, school absence, enrolment and operational issues. The Ministry of Education provides specific guidance to schools, and identifies resources that will support schools in the form of professional development, and through provision of infrastructure and development funds.

1.2 Policy drivers for a new approach

A number of policy drivers provided a mandate for a new approach to ‘circuit break’ the decline of RPPS and RDS schools and support improvement.

The revision of the Education Act in 2017 included reference to the need for ‘more graduated range of interventions’ to ensure swift support was available to schools. There was an acknowledgement that while the support needs to be targeted to have most impact, it cannot be short-term or piecemeal. The Act also supported alignment in processes and practices between the Ministry and ERO. As noted above both agencies have complementary, but different roles in school evaluation and school improvement. As a result of the update to the Education Act, both agencies have been working on new protocols, systems and processes for working together.

Signal Loss, a NZ initiative publication pointed to the need for the education system to urgently address the ongoing underperformance of schools. While the report acknowledged the contextual conditions that influence student outcomes, it made a strong case for intentional use of data and evidence to inform improvement.

The report identified that "some schools, despite intervention, perform poorly for as long as, and in some cases, longer than, the entire school career of their students - with possibly serious implications for the students in them and the state of our nation".

A report by Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce (2019) identified a range of systemic changes to support improved outcomes for students. There was a call for a shift to a high trust education system to spread of effective practices, and supports ongoing improvement. The report called for ERO, the Ministry and other agencies to work in coordinated and relational ways with schools to support improvement.

These policy drivers provided the authority for a new way of supporting schools that were experiencing ongoing performance challenges.

1.3 Rationale for The Turnaround Schools Pilot

The Turnaround Schools (TAS) pilot was implemented from 2017-2020. The strategic purpose of the pilot was to develop and trial an appropriate approach to identify the root causes of poor performance, and collaboratively work with schools and the Ministry to support school improvement. The stated purpose of the TAS pilot was to ‘intervene, disrupt the decline, highlight the systems that are required to shift, build internal capability and capacity, increase the momentum for change and support the school to enter a recovery phase.’ (School Turnaround Evaluation Methodology).

An assessment of pilot documentation for this external evaluation indicates three different, but interrelated objectives of the pilot.

The first objective was to develop and implement an approach to interrupt the decline of poorly performing schools. Monitoring and evaluation by the team was identified as the key lever or catalyst for improvement. The pilot was designed to contribute to a school’s evidence base about organisational, practical and academic issues that were influencing student outcomes, so that schools could plan and implement strategies for improvement.

The second objective was to develop and implement an approach to draw on the system and sector supports required for these high priority schools. There was a recognition that a single agency approach would not be sufficient. ERO could not ‘turn schools around’ with monitoring and evaluation mechanisms without the support of the Ministry. The Ministry needed evidence of school performance to identify support requirements. The collaborative platform between the two agencies and NZSTA was identified as key to success.

The third objective of the pilot approach was to enhance evaluative capability within the schools. One indicator of improved evaluative capacity may be the school’s use or intention to use data to inform improvement. It was envisaged that through the pilot the six schools would have the opportunity to learn about the value of data, how data can be used for planning and improvement through term by term reviews, and implement changes that will create and sustain improvements.

1.4 Timeline for Development

The timeline and key activities of the TAS pilot from initiation to implementation with the six schools are presented in Fig 1.

Fig 1: Development Timeframe

October 2016-February 2017

Ministerial papers compiled by ERO and the Ministry of Education identified and scoped school performance issues in schools of concern

February to June, 2017

Development of Joint Strategy: A strategy was developed that included roles and responsibilities of both agencies (Ministry of Education and ERO)

Internal strategy development by ERO of the TAS Pilot

ERO identified experienced evaluators from across the regions to form the national team

ERO met with the Ministry of Education Lead advisor and their team

April-May, 2017

The project manager was appointed and the project plan developed

June, 2017

Six schools were selected into the pilot from 18 potential schools

July, 2017-Early August

ERO developed the methodology and key phases and steps, and team training was conducted. ERO and

Mininstry meetings convened regular meetings. ERO met with NZQA to share information and establish communication approach.

August-September, 2017 Pilot commences: Four schools initially then two further schools join the pilot early in 2018.

Section 2: Evaluation of the TAS Pilot

The External Evaluation of the pilot

An external evaluation of the pilot approach was commissioned in March 2020. The pilot evolved into the High Priority Schools (HPS) in mid 2020 and the team has extended their reach to a wider number of schools. The focus of the external evaluation is on the TAS Pilot 2017-2020, not the HPS project.

The evaluation fieldwork for the TAS external evaluation formally commenced in July 2020[2]. The external evaluation was explicitly framed as an evaluation of the TAS approach, not of the schools.

This report presents the findings of an external evaluation. It describes perspectives from key stakeholders about TAS components, their effectiveness, strengths and weaknesses and opportunities for improvement.

Interviews were conducted with 26 stakeholders, including Principals and Board Chairs of the six schools, ERO Regional Directors and individual members of the TAS team, Ministry representatives from each region (managers and some advisors) and LSMs (where present in the school).

The report presents key findings from the evaluation. It is intended that the findings and recommendations in this report will be used to shape decisions about the merit and worth of the pilot. It is envisaged that these learnings will also inform the continued work of the HPS team, and contribute to the knowledge base within ERO and the Ministry about what works to support improvement in schools.

The key evaluation questions orienting the evaluation were:

- How was the TAS pilot intended to work to support school turnaround?

- How effective was the Turnaround Schools (TAS) Pilot in supporting school improvement?

- In what ways could the approach be improved to better reach schools with performance challenges?

- What are the lessons learned about effective strategies for school improvement within persistently low performing schools?

2.1 Framing the Evaluation

The evaluation questions require knowledge about the work undertaken by the TAS team with the schools, and the outcomes that were achieved through pilot activities.

This external evaluation focuses on the contribution[3] of the TAS pilot to changes from the perspectives of a range of stakeholders. Secondary data obtained from TAS review reports, and student outcome data provided a further source of evidence.

2.2 Evaluation Methods and Sources

The methods and sources of information generated through the evaluation included:

- Interviews with each member of the TAS team, about their role in the team, and schools they were appointed to as the TAS anchor.

- Visits to four of the six schools[4]. A key part of the visit was to gain an understanding of the context in which the school was located.

- Interviews with all six principals and Board chairs. In two schools with relatively new Board chairs, the previous Board chair was also interviewed.

- Semi-structured interviews with the Manager of Education, and Directors in all regions. These interviews were primarily conducted primarily by Zoom, and in some cases managers, and advisors from the regions attended to provide their perspectives.

- A group interview with the three regional directors within ERO

- Secondary document analysis and review of ERO reports and relevant, support documentation.

- Three evaluation forums with ERO and Ministry stakeholders, and with the TAS team to review findings and recommendations.

The schools that participated in the TAS pilot are not identified in this report by name. The decision was made to de-identify the schools to protect their privacy.

A summary of the evaluation methods and sources according to key evaluation question is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Evaluation Questions and Data Matrix

|

Key Evaluation Question |

Information Requirements |

Data Sources |

Method of data collection or retrieval |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. How was the TAS pilot intended to work to support school turnaround? |

-Description of the TAS model/approach and assumptions. How was the TAS approach different from other ERO reviews? How was the TAS pilot intended to work to support school turnaround? |

- The TAS Team (6) - Regional Directors (3) - Pilot documentation |

-Zoom individual interview. -Zoom small group interview -File review |

|

2. How effective was the Turnaround Schools (TAS) pilot in supporting school improvement the six schools?

|

-Assessment of shifts in student outcomes from baseline -Analysis of contribution: Views of the school representatives (Principal and Board) involved. – Perspectives of Ministry partners and regional directors within ERO |

-Quantitative data available on school outcomes from baseline (2016). Including NZEA level 1 and Level 2, Attendance data |

-Retrieval from TAS Files and secondary analysis -Interview x 2 with TAS team member with responsibility for data support) |

|

3. In what ways could the pilot have been improved? |

-Identification of conditions associated with success -Stakeholders’ views of strengths and weaknesses -ERO reports/partnerships

|

- Regional Directors (ERO x 3) -Regional Directors (5), Manager (4) Advisors (2) - Ministry of Education Manager -Principals (6), LSM (2), Board Chairs (5) plus immediate past Board chair (2 schools) -Feedback forums (x3) |

-Zoom small group interview - Zoom interview and one face to face interview -Face to face interview (1) -Face to face (11) and Zoom interviews (4) |

|

4. What are the lessons learned in terms of what works to support schools with ongoing performance challenges? |

-What were the changes that occurred in schools that are attributed to the pilot? -Learnings from the pilot -What is the likely sustainability of these changes given objectives, scope and resourcing? |

- Regional Directors (ERO x 3) -Regional Directors (5), Manager (4) Advisors (2) - Ministry of Education Manager -Principals (6), LSM (2), Board Chairs (5) plus immediate past Board chair (2 schools) -Feedback forums (x3) |

-Zoom small group interview - Zoom interview and one face to face interview -Face to face interview (1) -Face to face (11) and Zoom interviews (4) |

2.3 Scope of the Evaluation

Data collection activities for the external evaluation occurred over a four-month period – from late June to September, 2020. All primary data collection and analysis was undertaken during this time. For most of the TAS schools the start of 2020 was their third year of involvement with the TAS pilot.

Principals of the six schools were interviewed as well as the current board chair, and immediate past board chair (if appropriate). Interviews with boards as a governance group, and interviews with Whānau or community members were outside of scope of this external evaluation.

As a key partner, Ministry representatives were also interviewed at the National leadership level, and at the regional level. Group zoom interviews were conducted with regional directors, managers and advisors. A small group interview was also held with regional directors of the three ERO regions.

The evaluator had access to a range of other pilot documentation, including project files, progress notes, email communications, and reports over time, and school level information about each of the schools involved. In addition, secondary data, that is quantitative data on achievement in NCEA, school leaver data and attendance data was retrieved from ERO reports to supplement the extensive primary qualitative data gathered during the evaluation.

This report focuses on the effectiveness of the TAS pilot from the perspective of key stakeholders.

2.4. Audience and Key Stakeholders

The key audiences for this evaluation are Nick Pole (CEO) and Jane Lee (Deputy Chief Executive, Review and Improvement) of the Education Review Office, and Jann Marshall in her role within the Ministry of Education as the Acting Associate Deputy Secretary, Sector Enablement and Support. The report is intended to inform decisions about the merit and worth of the TAS pilot, and to identify lessons learned that may inform further joint work with schools experiencing performance challenges.

2.5 Limitations of the Evaluation

The evaluation relied on a range of methods and sources to generate claims about the value of the program. However, there are a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged.

No observation of the TAS team in practice: The evaluator gathered information from the schools about their experience with the TAS pilot, and their perspectives on the way the TAS team worked with schools, and with the Ministry. Although the key activities of the TAS team were described by the team, and by stakeholders, no observations of school reviews were conducted.

No consultation with community members: A school is part of its community. From the perspective of many stakeholders, the school cannot be considered in isolation from the wider community. The scope of the current evaluation did not allow an opportunity for consultation with members of the wider community.

No opportunity to consult with NZSTA personnel working in the schools: The evaluator recognises that the education system represents a partnership among a range of agencies and personnel. In the TAS pilot this includes the schools, and communities in which the school is embedded, the Ministry, ERO and NZSTA. There was no scope in this evaluation to conduct interviews with NZSTA personnel who had supported any of the six schools. Similarly, there was no opportunity to consult with any other individuals who supported school improvement (e.g., SAFs, curriculum advisors).

Reliance on either self-report data or accounts of change: The qualitative data gathered during the evaluation painted a rich picture of how the TAS pilot worked with schools. Interviews with managers and school stakeholders were helpful in understanding the context of each school, and perspectives on the school’s improvement journey. However, these perspectives were not substantively validated by any other source.

While quantitative data was retrieved for key quantitative outcome measures over several years to allow some comparative analysis, the outcomes are at the whole school level, and do not necessarily show the granularity of change within the school, nor do they demonstrate the contribution of the pilot to school outcomes. Data is not included in this report to ensure that schools are not identifiable. Only global patterns are presented.

2.6 A note about attribution and contribution

The TAS pilot was a key mechanism for gathering evidence about the issues of concern within the school, and for tracking progress. The external evaluation gathered information to describe and document the implementation, and assess the effectiveness of TAS in improving school performance in the six schools. The focus of the external evaluation was on stakeholders’ views of the value of the TAS pilot in progressing change within the schools. Stakeholders were encouraged to share their observations about the contribution of the TAS to these changes. Secondary data on student outcomes from baseline to 2019 were also drawn on to align perspectives with actual shifts over the past three years.

In public policy evaluation it can be challenging to disentangle the influence of an intervention or project from other influences in the context, such as other educational support provided during the pilot timeframe, the progressive maturity of leaders and teachers, support provided by the Ministry and other agencies, and contextual changes emerging over time[5].

Initiatives external to the TAS pilot will also have contributed to observed school improvements. For example, the engagement of an LSM (in three of the six schools), the appointment of a new Board, or implementation of curriculum support specialists are other key supports of change. While it cannot be claimed that any improvements are a direct result of the TAS pilot, triangulation of data from schools, the TAS team and Ministry representatives builds a credible evidence base for claims made about effectiveness in this report.

Section 3: What is the TAS Pilot and how does it work?

3.1 A programme logic map for the TAS pilot

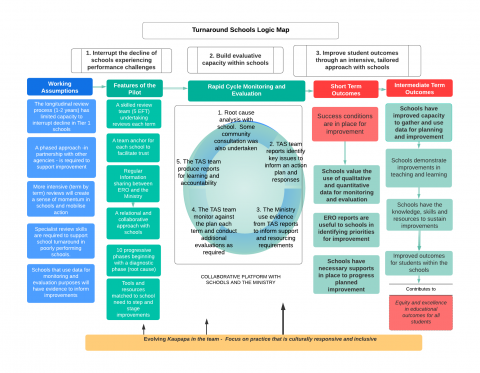

A programme logic map (or logic map) was developed during the evaluation process to provide a structure to data collection and to summarise the pilot on a page.

A logic map is a one-page depiction of the relationship between drivers, inputs, activities and intended outcomes. In other words, it shows the relationship between what is done and what happens as a result. These maps are useful in understanding an initiative's intent, but also for developing tailored performance measures and focusing evaluation data collection options. The logic map informed the development of propositions about the relationship between TAS activities and outcomes that could then be subsequently tested during the evaluation.

As the external evaluation evolved, the logic map was elaborated. The map is presented in Figure 2. The diagram should be read from left to right.

The external evaluation focused attention on the relationship between the activities undertaken by the TAS team and short-term outcomes.

Fig 2: Logic Map

A diagram with a header that reads "Turnaround Schools Logic Map". It largely consists of five columns with a smaller, circular diagram in the middle.

At the top are three sub-headers that span the width of the diagram:

1. Interrupt the decline of schools experiencing performance challenges

2. Build evaluative capacity within schools

3. Improve student outcomes through an intensive, tailored approach with schools

The first column has a header reading "Working Assumptions". It contains five sections, from top to bottom:

- The longitudinal review process (1-2 years) has limited capacity to interrupt decline in Tier 1 schools

- A phased approach - in partnership with other agencies - is required to support improvement

- More intensive (term by term) reviews will create a sense of momentum in schools and mobilise action

- Specialist review skills are required to support school turnaround in poorly performing schools.

- Schools that use data for monitoring and evaluation purposes will have evidence to inform improvements

An arrow points to the next column, titled "Features of the Pilot". It contains six sections, from top to bottom:

- A skilled review team (5 EFT) undertaking reviews each term

- A team anchor for each school to facilitate trust

- Regular Information sharing between ERO and the Ministry

- A relational and collaborative approach with schools

- 10 progressive phases beginning with a diagnostic phase (root cause)

- Tools and resources matched to school need to step and stage improvements

An arrow points to the next header, "Rapid Cycle Monitoring and Evaluation". Below this sits a circular diagram with five points placed around it in a clock-wise order:

- Root cause analysis with school. Some community consultation was also undertaken

- TAS team reports identily key issues to inform an action plan and responses

- The Ministry use evidence from TAS reports to inform support and resourcing requirements

- The TAS team monitor against the plan each term and conduct additional evaluations as required

- The TAS team produce reports for learning and accountability

Below the diagram reads "Collaborative Platform with Schools and the Ministry".

An arrow points to the next header, "Short Term Outcomes". It is a column that contains four sections, from top to bottom:

- Success conditions are in place for improvement

- Schools value the use of qualitative and quantitative data for monitoring and evaluation

- ERO reports are useful to schools in identifying priorities for improvement

- Schools have necessary supports in place to progress planned improvement

An arrow points to the next column, titled "Intermediate Term Outcomes". It contains four sections, from top to bottom:

- Schools have improved capacity to gather and use data for planning and improvement

- Schools demonstrate improvements in teaching and learning

- Schools have the knowledge, skills and resources to sustain improvements

- Improved outcomes for students within the schools

Below is an addition section labeled "Contributes to"

- Equity and excellence in educational outcomes for all students

Across the bottom of the diagram is box with text that reads "Evolving Kaupapa in the team - Focus on practice that is culturally responsive and inclusive". It has arrows that point upwards, roughly towards the "Features of the Pilot" and "Rapid Cycle Monitoring and Evaluation" sections.

3.2 What were the key drivers for the new approach?

There are a range of issues that cumulatively pose barriers to improvement in schools classified as repeatedly poorly performing schools (RPPS) or those in rapid decline (RDS).

Many of challenges identified in RPPS and RDS relate to one of the following performance dimensions:

- Health and Safety

- Stewardship and Governance

- Leadership

- Teacher motivation and performance

- Quality of teaching and responsive curriculum

- Positive learning culture and learning environment

Conventional review strategies have not generally been effective in turning around performance in these schools. Reviews focus attention on indicators, and inform schools of barriers that are inhibiting performance, but reviewers may not have sufficient time to identify the root causes of performance challenges. Standard 1-2 year reviews may also not be sufficiently intensive to mobilise action, or build the school’s capacity for improvement.

The architects of the TAS pilot recognised that the conditions that influence student outcomes are often found in the school – its structure, processes and practices. Attention must be paid to growing the capacity of the school if sustainable changes are to be made.

A set of propositions[6] underpin the pilot and were considered as part of the evaluation. The propositions were:

- That an intensive review (each term) will be an effective strategy to ‘turn schools around’

- That a collaborative platform will increase the school’s ownership of required improvements

- That the dose of the pilot (termly reviews) will be sufficient to mobilise school stakeholders to progress improvements

- That an experienced group of reviewers is required to work with schools experiencing performance challenges. The proposition to be considered is that the specialist skills of the team will be a good fit for the school and its wider context

- That a dedicated ‘anchor’ for each school will facilitate trust and continuity

- That a phased approach to evaluation between key agencies - the school, ERO and the Ministry is required to build a solid evidence base for improvement, and support school capacity in monitoring and evaluation

- That the outcomes achieved are sufficiently valued by stakeholders to warrant the level of investment.

3.3 How was the TAS Approach different from 1-2 year reviews?

ERO monitors, evaluates and report on educational outcomes for children and young people. Evidence gathered from reviews can be used as a ‘catalyst for change’ for improving schools and the wider education system within New Zealand. The historical focus within ERO tended to privilege the accountability function of evaluation, which was appropriate in the context of the organisation’s role. The TAS pilot was different.

A major difference of the TAS approach from 1-2 year reviews was its intensity. Reviewers from the team returned to the school each term to collect and analyse data. They were able to initiate a staged approach to improvement with the schools.

The ongoing interaction with the school required a different approach to the professional relationship. Reviewers focused initially on building a collaborative platform, between the reviewer and the school, and with the Ministry.

Each review was scheduled with the school, and the process discussed with the school and regional managers. At least two reviewers participated in each review. One reviewer was appointed as the anchor for the school to ensure continuity.

Reviewers modelled evaluative skills and encouraged the schools to use data for school planning and for tracking improvement.[7] The team was able to triangulate their observations and interpretation of key issues to sharpen judgements. The feedback conversations were not always easy- for the reviewers or for the schools. Reviewers were able to present issues clearly and assertively with the confidence that other members of the team would back them up. The reviewers made a concerted effort to focus on a small number of issues so as not to overwhelm the school. There was a tension here on occasion where there were several issues that needed to be addressed for accountability reasons (for example, health and safety issues within the school and other issues posing potential risk).

While ERO has committed itself as an organisation to be culturally responsive, in TAS this focus was made very explicit. The team acknowledged the importance of Kaupapa Māori and initiated ways of working to operationalise the principles into practice within culturally diverse settings. This work has been aligned with He Taura Here Tangata Strategy[8].

A report was completed as soon as possible following the review. Often, reviewers sent emails with a summary of the review. The majority of principals in the six schools had experienced an ERO review before in previous work in other schools.

The three quotes presented below were shared by school principals involved in the pilot. They powerfully highlight perspectives about the difference between a ‘standard’ ERO review and the TAS review process

Working together towards positive outcomes

‘…The ERO approach before this was that they come into the school, write some report and then they walk away. So, over the whole period of the (TAS) project, there has been a very strong level of support in the sense that we have always been working together towards positive outcomes for improvement in our school. And you can’t do that by just simply evaluating. You can’t just do that by measuring. It won’t work.’ (School 3 - Principal)

A very different experience

‘The model of ERO going into a school, creating havoc, walking away leaving the school to deal with the aftermath and all the blood on the floor, was one that the team discarded. I guess supporting school improvement hasn’t been part of an [ERO] model, it’s always just been a bit “We’re here to review. We’re going to tell you what you’re not doing very well”…This pilot was a very different experience.’ (School 4 - Principal)

Warts and all conversations

‘(The difference for me was that) they (The TAS team) had a genuine desire to work with us, which I really liked…In all the visits, we were able to critique and challenge any of the things that they had found or that we didn’t agree with. We developed a kind of trust where we were not sort of frightened of having a ‘warts and all’ kind of discussion…We’re working on this together. We are all wanting the same thing’ (School 5 - Principal)

3.4 Underpinning Principles and Approach

The school turnaround methodology was based on principles of Developmental evaluation (Patton, 2011), Rapid review approaches to monitoring and evaluation (Kumar, 1993) and Kaupapa Māori.[9]

Developmental evaluation (DE) has much in common with an educational action research cycle, but is more explicitly focused on collaboratively identifying opportunities for innovation. DE allows for emergence and adaptation as an initiative unfolds. Following a recipe for improvement is not appropriate in this approach to evaluation. In an educational context the evaluator works with schools to identify, co-design and co-construct data to inform improvement. Creative ideas are celebrated, trialed and evaluated progressively.

The use of rapid review approaches complements Developmental evaluation in that these approaches support the ongoing process of improvement and organisational learning. Rapid approaches are particularly relevant in contexts where timely feedback on progress is required to support the next improvement step. In the TAS pilot the team recognised that strategies were required to generate and share data effectively and efficiently each term with the schools.

It was acknowledged by the team that the TAS methodology and implementation of the pilot would necessarily evolve over time. As the team became more experienced in undertaking specific reviews, there was increased attention paid to the cultural responsiveness of the team’s approach[10]. The original Kaupapa (approach) that guided the TAS pilot explicitly identified the importance of cultural responsiveness and relational ways of working. The TAS pilot aimed to be inclusive of Kawa-Tikanga (ways of doing and being), Whakaaro Hōhonutanga (Deep thinking), Whakawhanaungatanga (relationships and partnerships), Hitoria-Whakapapa Tangata (History, genealogy and Connections, and Kia Māia, Kia Mataara (Courage and Leadership).

These principles influenced how the team engaged with the school, how they built relationships within the schools and with their boards, and how they undertook data gathering, analysis and synthesis activities. The team recognised that they needed to be bold, and step up to challenging conversations. But, they realised that without a platform of trust, respect, authenticity and transparency among all partners, sustainable change would not be likely.

‘You’ve got a cultural dynamic, which cannot be ignored – the relationship between the Iwi and the school…Any approach needs to be mindful of the wider context of the area...Whatever you do in that area from a cultural perspective you have to also consider the wider implications around the wider tribal boundaries.’ (Regional Director, Ministry of Education)

The TAS Team summarised principles and implementation stages of their approach in a range of documents produced through the pilot. These resources were shared internally within the team to support review work. Others have been shared within and across other teams within ERO.

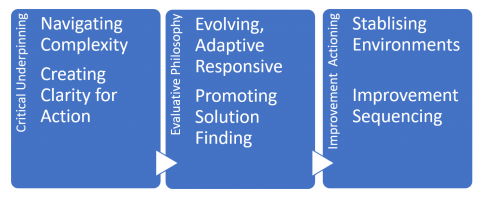

The team produced a summary diagram that define three elements that differentiate the TAS approach from the longitudinal review. The three elements are:

- Critical underpinning principles – an acknowledgement of complexity and the need for clarity to drive actions within schools

- Evaluative philosophy –The evaluation approach, informed by Developmental Evaluation and rapid cycle approaches, recognises that evaluators must be adaptive and responsive to context. The reviewer’s role in part is to promote capacity within schools to identify workable solutions. Different strategies may be required for different school contexts.

- Improvement Actioning – A key role for the TAS team is to provide schools with evidence that supports action. The evidence needs to be stepped and sequenced so that change plans are doable. This provides a stabilising environment for improvement activities to occur.

The manager of the TAS team provided the evaluator with the following diagram to represent these key elements.

Fig 3: TAS Team Philosophy and Approach

Critical Underpinning:

Navigating Complexity

Creating Clarity for Action

Evaluative Philosophy:

Evolving Adaptive Responsive

Promoting

Solution Finding

Improvement Actioning:

Stablising Environments

Improvement Sequencing

3.5 How was TAS intended to work in practice?

As noted in an earlier section of this report, the pilot involved an intensive school improvement approach using the lever of monitoring and evaluation as a catalyst for change. The reports -based on data collection at the school each term -generated evidence of issues and challenges within the school that were inhibiting student outcomes. It was envisaged that schools, with the support of the Ministry, would then use this evidence to develop an action plan. Term by term reviews provided an opportunity to map progress against the plan.

The pilot incorporated ten phases. Schools progress through the phases, developing local solutions to challenging performance issues. While the ten phases appear to be linear, the practice was not. The team recognised that schools were at different places, and had differing needs. There needed to be a level of adaptation, and flexibility in implementation according to context.

Research on school improvement has identified that improvement efforts often fail to probe deeply into why schools have experienced decline in the first place (Duke & Hochbein, 2008; Meyer & Zucker, 1989; Stringfield, 1998). Without this knowledge solutions may not be well targeted or relevant to the school context. Different school contexts may require different change mechanisms.

A key part of the initial phase was diagnostic with an explicit focus on root cause analysis. The school evaluation indicators were elaborated within the context of poor performing schools. Sub-stages and actions were identified to support schools in setting priorities, in an appropriate sequence to guide their own assessment of progress. This diagnostic phase provided an evidence base for the school to inform the school’s development of an action plan.

The team was required to work swiftly during term reviews with the schools. At the end of the face to face review, a verbal summary of key findings was presented to the principal and often to the board. A report on progress, challenges and required actions was also produced from the review.

Subsequent phases built from the diagnostic, and allowed the team to review progress against the plan and the previous review, and to facilitate capacity in the school’s use of data for planning and improvement.

A range of resources and tools were developed by the TAS Team over the course of the pilot. The use of particular tools was informed by an assessment of the relevance to the context and issues faced by the school. One of the tools, the ‘qualitative radars’ for school improvement is a creative, visual way to depict observed shifts in key organisational conditions within schools over time. The conditions are aligned with established markers of school performance in the School Evaluation Indicators including safety, wellbeing, stewardship, leadership, evaluation capacity, connections curriculum, climate, culture, and outcomes. The radars have not yet been shared with the schools, but have informed briefings within ERO and with the Ministry.

3.5.1 The schools selected in the pilot

Six schools were nominated to participate in the pilot. The schools were all Tier one schools, which means they have not improved their performance over four years through at least two successive ERO one or two year evaluation cycles. The schools included two large urban secondary schools, a medium-sized high school, a composite school offering years 1-13, and a very small rural primary school.

They were classified as repeatedly poor performing schools and/or schools in a rapid spiral of decline. The schools were located across New Zealand, five schools in the North Island and one in South Island.

A brief summary of the characteristics of the pilot schools is presented in Table 2.

Table 3: School Location and Key Characteristics

The schools are not identified in this report for privacy reasons. The presentation of the key characteristics of the schools (composition and school size) is therefore presented in general terms.

Table 3: Key characteristics of schools in the pilot

|

Schools in the TAS Pilot |

|

|---|---|

|

School 1 |

A medium-sized school in the north island. The majority of students identify as Māori. There are approximately 250 enrolled students.

|

|

School 2 |

Very small rural school catering for children in years 1-8. There are under 50 enrolled students in this school who all identify as Māori.

|

|

School 3 |

Small rural school in the South Island catering to students in years 1-13. The school population is approximately 150.

|

|

School 4 |

A very large urban secondary school of over 1000 students that offers years 9-13. The majority of the student population identifies as Māori or as from a Pacific heritage.

|

|

School 5 |

A large high school catering for students in Years 9-13. Most students identify as Māori. Nearly a third of the students identify as Samoan, Tongan or as Cook Island Māori. The school has an enrolled population of approximately 500 students.

|

|

School 6 |

Small rural composite school catering for approximately 100 students across years 1-15. The majority of the students enrolled in the school identify as Māori.

|

3.5.2 The Specialist Improvement Team of Review Officers (SIRO)

The intensity of focus, the challenges of working in a dynamic and complex school environment with diverse stakeholders, and the collaborative sense-making process that underpinned TAS required a skilled review team. They needed to be experienced in school review contexts, possess strong relational skills, have the capacity to be adaptive (rather than reactive), and be able to bridge the role of evaluator and guide.

A team of five experienced review officers were seconded to work in the TAS team under the direction of a national manager. For the first year of the pilot there were only 2 EFT personnel in the team with the other team members seconded from various regions across the country for TAS reviews as required. During this time these individuals were also responsible for completing existing reviews in their region. This contributed to some challenges in scheduling reviews, and added an additional workload on top of the work associated with the TAS pilot.

A full-time national team was put in place in October, 2019. As of September, 2020 there were five full time equivalent reviewers, under the direction of the national project manager.

Attention was paid to aligning the skill set and review approach believed to be appropriate for each school. Eight other ERO reviewers have been drawn into work on specialist reviews or specific issues with the core TAS team. For example, a Samoan reviewer led the special review of a Samoan bilingual programme in an English medium setting at one of the schools.

The TAS Team Anchor

One member of the TAS team was appointed as anchor for each school. This ensured some level of continuity between reviews, and a point of contact for the school and the Ministry.

This individual was the first point of contact for the school, and that- where possible- this team member was available for each termly review to the school to promote continuity. As the team was small in size, most schools had the opportunity to work with a generally consistent team across terms.

The core members of the team met together once a term to discuss progress in the six schools, consolidate observations, and plan next steps. These team meetings also provided the opportunity for reviewers to debrief about challenges and share strategies that had been effective in working with the schools. Informally, the team maintained regular contact via phone calls and email.

A pilot generally evolves during implementation. Initial plans may change as context may demand a different approach. Strategies the team adopted with schools shifted as the team learned about what worked and what didn’t work.

There was a strong commitment to culturally responsive and inclusive practice from the beginning of the pilot, but how this was enacted developed over the timeframe. In two schools, the TAS team lead was an experienced Māori reviewer, and initiated and conducted the reviews with a Kaupapa Māori lens based on lived experience and knowledge. The Māori reviewer facilitated respectful conversations between Kaiako (educators), tamariki (children), and whānau (families) to inform school improvement. On specialist reviews involving Māori or Pasifika students, specialist Māori or Pasifika reviewers led parts of the review.

Consider who engages

‘You need to actually spend time to unpack what the context looks like and what the approach should be so that is responsive in a cultural way. That often means not just considering how to engage but (thinking about) who does the engaging.’ (Ministry of Education representative)

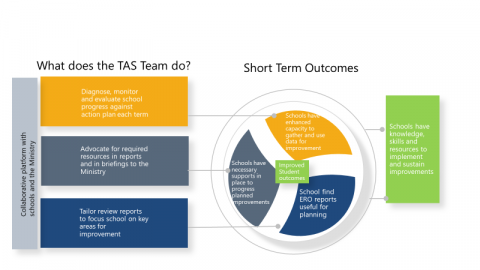

3.5.3 What did the team do?

The composition of the team that went to each school each term was carefully considered in terms of required knowledge, relational style and ‘fit’ with the school context. At least two team members attended each review to the school. Team members were rotated across schools according to availability for scheduled reviews, and balance with other commitments. The team, therefore, had some familiarity with all six TAS schools, and a deeper knowledge of one or two schools as its anchor person.

Conducting the reviews in pairs or in small groups ensured that team members had the opportunity to triangulate observations with a colleague, and facilitated the team’s capacity to manage - sometimes challenging - feedback processes with school stakeholders.

During the one to two days of the review each term the reviewers consulted with the principal and the board, undertook observation and interviews with teachers and students, and documented observations about a range of dimensions, including teaching and learning, curriculum, health and safety, stewardship. Issues emerging from the review were shared and discussed with the regional manager or advisor within the Ministry.

There were 24 outputs required each year for the pilot. These equated to reports of reviews – either internal to the school reports or external public reports. In some cases lengthy email summaries of the major findings, progress of the school and issues for attention were generated and sent to the principal, board chair, LSM and Ministry representatives if they had attended the initial feedback meeting with the school.

3.6 What were the intended outcomes of the pilot?

The pilot was designed to develop and implement an approach that would progress outcomes within the six schools. It was anticipated that through collaborative ways of working with the school that in the short term that the school stakeholders would demonstrate commitment and enthusiasm for change. The TAS reports were intended to focus on the key issues within the school that were most urgent so that the school could progressively focus on actions for improvement.

An assumption was that the trusting professional relationship created through term by term reviews, and the provision of progress data would improve capacity for reflective practice and the development of targeted action plans.

The TAS team envisaged that the regularity of the reviews would lead school stakeholders (particularly the leadership team and the Board) to an appreciation of the value of qualitative and quantitative data in assessing school outcomes and improving practice.

In the intermediate term the working assumption was that the collaborative work with schools, and their access to additional support and resources will improve understanding of the attributes of quality teaching and learning practices. In time the schools will exhibit more confidence in applying these principles with students in the classroom.

In the longer term, outside of the initial pilot timeframe, achievement of these short and intermediate term outcomes was associated with the implementation of actions that will contribute to positive and sustainable changes in the school environment and shifts in student outcomes. Schools will have developed the skills and the resilience necessary to navigate structural and contextual challenges in the future.

3.7 Context Matters – Turnaround Schools in Context

It is reasonable to expect that senior leaders, teachers and Boards want the best outcomes for their students. They recognise that education can escalate young people out of social disadvantage. But, they also recognise that the circumstances many of their students face at home, in the community, and in the school may inhibit full engagement with learning.

Principals of all the schools highlighted the importance of context to the success of any improvement strategy. Lifting student outcomes in a secondary school setting is complex in circumstances when the students come to the school with lower than anticipated skills in reading, writing and numeracy. School attendance may also be sporadic because of family commitments, care-taking responsibilities, or because of long-term disengagement with education.

Young people in schools in these communities may experience social exclusion arising from a combination of social issues such as, family or intergenerational unemployment, low family income, poor quality or overcrowded housing, high crime, poor health and family breakdown. These issues are often mutually reinforcing. Compounding the problems is that many of the lowest-performing high schools are at a severe disadvantage because their feeder schools may also experience challenges. Students arrive in high school with major learning challenges, and this further threatens their level of engagement with formal education. While the academic problems in these schools are challenging, ‘the pervasive social problems of poverty — discouragement, distrust and low expectations — are often even bigger barriers to success.’[11] (pg 1)

Three examples shared with the evaluator by the principals portray the kinds of challenges that schools face in supporting student achievement. These examples are not meant to sensationalise the issues and are not offered as excuses for poor performance. Rather, they point to the need to understand the context in which educators work, and the potential challenges they experience in ‘turning their school’ around. A common theme from these examples was the need to get the school culture ‘right’ and raise student expectations before implementing formal strategies to shift student achievement.

A neglected school

School 1: I didn’t think it was possible to be shocked by the condition of a school. I have quite a bit of experience and thought whatever I was walking into I would be able to manage. But, I was shocked when I came here. The physical condition of the buildings was poor, and in the past several years there had been little or no money spent on the library or on refurbishment of buildings or equipment. In one meeting I remember seeing a rat running across the floor… It felt like the school had been neglected for years. Attendance and engagement in classrooms was really low. Student behaviour was challenging. The Police came onto the premises at least daily to address concerns or issues with fighting, violence or damage to property. It was an expectation they would be here, not an exception. Our focus here has been to work to get students engaged, to welcome them when they come to school, and make learning interesting to them.

Lack of services and support in the community

School 5: This community experiences a lot of social and economic disadvantage. When I came here the roll was dropping, and there just didn’t seem to be any confidence in the school. The area has high levels of unemployment, poverty, crime and youth crime. Students were coming to school unable to read and write at the expected level. They may have had patchy attendance at the primary school and they may not be that engaged in education. The first thing I had to do was to work on the culture of the school. If you don’t get that right you don’t get anything right. We have made a concerted effort to change the culture of the school and the language that we use to describe how we operate as a school in every area in terms of our management of and care of our students.

The Principals’ office as a triage room

School 6: When I first came here my office was like a triage room. The table was covered in incident reports – mostly involving students, but some involving staff as well. There was very little order in the school. For years there had been inconsistent leadership and it took time just to settle the students. I would speak to students about behaviour issues and they seemed surprised that I was following things up with them. They didn’t realise there were consequences. There are not many of the services we need in this community. A number of the families in this community experience drug and alcohol issues, but the services available in the community do not address the level of need. On one occasion I took a student in my car to get him the support he needed. The service was over an hour away…I would like to do some creative things…but a lot of my work in the first two years has just been getting the students settled.

Section 4: Evaluation Findings

The major findings of the external evaluation are presented in the following sections of this report. For each evaluation question, key findings are presented as bullet points. This will be helpful for readers who are interested in obtaining a quick overview of key messages. Each point is then elaborated in the narrative section with supportive evidence and interpretations. Direct quotations from key stakeholders that are relevant to the presentation are interspersed throughout the findings section.

4.1 What were stakeholders’ Impressions of the Pilot?

Impressions of the Pilot - overall

- Overall, the TAS pilot was highly regarded by school stakeholders. It was considered valuable as a mechanism for school improvement.

- Ministry of Education representatives were aware that the TAS pilot was a ‘different approach’ to school monitoring and evaluation. They were supportive of the explicit mandate for collaboration between the agencies.

- Ministry representatives in the regions indicated that initially there was a lack of clarity about the pilot, and how it would work. Regional Directors indicated there were ‘teething issues’ concerning communication about TAS processes, and progress made in schools. These issues were associated with a breakdown in communication, particularly in terms of sharing what was occurring in the pilot schools within the regions. Communication issues may also have been exacerbated by layers of reporting at the national and at the regional level and also a result of some turnover in staff. Communication between ERO and the Ministry appeared to improve over the course of pilot implementation.

ERO and the Ministry -on the same page

‘The ERO team and the Ministry worked really well together, very closely. And we have lots of conversations about what we are seeing and what is happening. We see things the same way, but bring different perspectives to the table. We are making a concerted effort to be on the same page about things because if the school hear a different message then one group can get played off against the other.’ (School 2, Ministry representative).

- Regional Directors within ERO were supportive of the core principles that underpinned the pilot approach. They identified the need for a stronger evidence base about how the model was intended to work in practice, and the evidence base for the approach to school evaluation. The model was a resource-intensive approach to school evaluation, so clear communication of the underpinning evidence for the approach to key internal and external agencies was required. One Director questioned the evidence base for focusing primarily on schools as agents of change, rather than the wider community. From this perspective the TAS model may have been overly optimistic in its objective to support school improvement primarily through evaluation mechanisms.

- There was a view that opportunities for internal collaboration between the TAS team and the regions within ERO did not always work well. While the TAS team shared information about progress within the TAS schools, the nature of the communication was often descriptive (focusing on specific issues within each school) rather than pitched at a strategic level.

- Principals generally welcomed being part of the pilot. They saw it as an opportunity to get additional support and/or resources for the school. One principal viewed the pilot as a way to get ‘direct’ support from the team with implementation of school improvements. However, direct support or advice was not the intention of the pilot. This expectation appeared to affect the school’s engagement with the TAS team, generated confusion about purpose, and negatively influenced perceptions of the value of pilot activities.

- Some board members did not appear to understand the difference between the pilot and other support offered by the Ministry of Education or LSMs (in the schools where they existed). While most board chairs were positive about the pilot, some were not clear about the differences in roles between representatives of the Ministry and ERO. It was evident that some Board Chairs had the impression that ERO reviews were predominantly a ‘tick and flick’ approach to ensure school accountability.

- In the three schools with an LSM, there appeared to be confusion about the roles and responsibilities of the TAS team, the LSM and the Board. An LSM in one school attempted to resolve the confusion by integrating ERO recommendations into the school’s action plan to clarify the relationship between reports and agreed actions.

- Principals were interested in ERO and the Ministry creating an opportunity to share learnings with other schools involved in the pilot. The quotation below illustrates the value of progressive sharing of findings through a pilot process. Other principals noted the value of a forum with all the schools involved to highlight learnings and share promising practices.

Value of progressive reflection

‘Every now and again I think it would be beneficial to call a ‘time out’. Bring the principals together and ask them how it is going. Are there things that we could be doing differently? Are there things the schools could do to support the project more? It would also support us (principals) in our learning through discussion. It would be a massive learning opportunity. “Why are you valuing this over that? I am interested in your thinking on that”.’ (School 4, Principal)

Perceptions of the Process

- Principals and board chairs appreciated working closely with the team anchor. This individual ensured some continuity between reviews, and became a trusted partner.

- The continuity of the team across school reviews was valued by school stakeholders. Working with the same team over time enhanced levels of trust, and facilitated ‘frank conversations’ about school improvement. However, three of the six principals noted that when other TAS team members attended the schools for reviews, there tended to be additional issues raised about school issues that had not been raised before, which they found frustrating.

Continuity of the Team

‘One of the things that was valuable was the continuity in the TAS team with schools because there was a growing understanding of the painpoints, and points of traction. A balance then needs to be struck between identifying the range of issues within a school that may be inhibiting improvement, and being realistic about what improvements can be made over a given timeframe. A balance also needs to be struck between providing evidence of gaps, and acknowledging progress or small wins.’

- Termly reviews created momentum for change. School stakeholders indicated they prepared for the ‘visits’, and in between developed action plans to address concerns outlined in ERO report. While this does not mean great gains were always made between reviews each term, the regularity of ERO contact with the schools appeared to mobilise reflection and action.

- The relational skills of the TAS team were highly valued. It was clear that TAS team members were viewed positively by school stakeholders. As the relationship between the reviewers and the schools developed, school stakeholders looked forward to the termly ‘visit’.

The two quotations presented below point to the level of professional respect and relational trust that was developed between school stakeholders and TAS team members: