Summary

New Zealand society has changed a lot over the years and as a result, our communities are becoming increasingly diverse. Auckland is our most culturally diverse city with over 100 ethnicities and more than 150 languages spoken daily. But cultural diversity is not just about what is happening in Auckland. Wellington’s Chinese New Year festival has been going for 18 years and Central Otago is about to form the 20th Multicultural Council in New Zealand – we are a truly multicultural nation.

As communities become more ethnically diverse, so does their student population. Diversity within schools can create positive interactions that stimulate the creativity of students. It can help recent migrants become more proficient in the language of their adopted country and can make children within the school less likely to ‘pre-judge’ and identify people by their ethnic group. Schools will need to think about how they embrace and engage with different communities as the ethnic diversity of their school increases.

This article explores how the ethnic diversity of the primary and secondary school roll has changed in New Zealand since 2009, and whether these changes are leading to more diverse or more segregated schools.

We measure ethnic diversity using the entropy index, which measures the distribution or diversity of the school roll across five ethnic groups (Māori, Pacific, Asian, New Zealand European, Other) within schools and regions. The Auckland region has the most ethnically diverse roll with 15.6 percent Māori, 20.0 percent Pacific, 21.1 percent Asian, 37.0 percent New Zealand European and 3.7 percent Other. On the other hand, in the Tasman region, 80 percent of the school population is New Zealand European. The use of broad ethnic groups will hide changes within these groups, such as changing migration patterns across Asia and an increasing number of students who have multiple ethnic backgrounds.

Whole article:

Ethnic diversity in New Zealand state schoolsThe New Zealand school roll is becoming more diverse

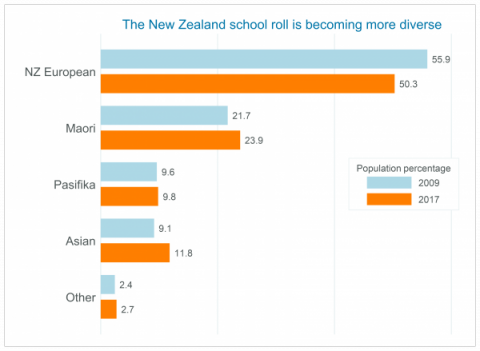

Nationally, the share of New Zealand European students in our schools has declined from 55.9 percent in 2009 to 50.3 percent in 2017, while Māori and Asian students have increased their share of the school roll. Māori students made up 23.9 percent of the school roll in 2017, compared to 21.7 percent in 2009. The proportion of Asian students in the school roll has increased by a third between 2009 and 2017, from 9.1 percent to 11.8 percent.

Compared to the diversity of the population as a whole, the New Zealand school roll is more ethnically diverse. There are a greater proportion of Māori and Pacific students, compared with the overall population. In 2017, 24 percent of students were Māori and 10 percent identified as Pacific, compared with 15 percent and seven percent respectively of the overall population at the time of the 2013 Census.

North Island vs South Island

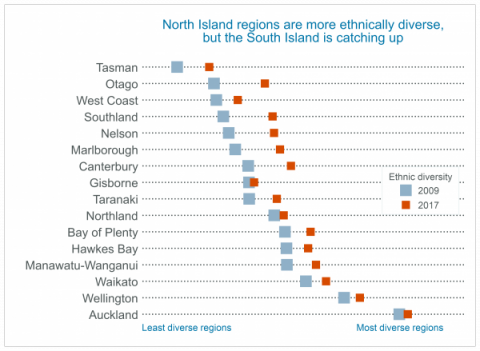

The ethnic diversity of schools increased in all regions across New Zealand between 2009 and 2017. The largest changes were evident in the regions that had the least amount of diversity in 2009 – consistent with the trend for increasing ethnic diversity across the country.

The Southland region experienced one of the largest increases in ethnic diversity within their primary and secondary schools. The proportion of Pacific students increase from two percent to three percent, and proportion of Asian students more than doubled from two percent to five percent. The West Coast was the only South Island region with a more modest increase in ethnic diversity (consistent with North Island regions).

Interestingly, while Auckland has the most ethnically diverse school roll among New Zealand regions in 2017, ethnic diversity has not increased very much since 2009. Gisborne and Northland also measured relatively small increases in diversity over this period.

The blue squares measure the overall ethnic diversity of a region in 2009 and the orange squares measure ethnic diversity in 2017. In 2017, the Auckland region had the most ethnically diverse role with 15.6 percent Māori, 20.0 percent Pacific, 21.1 percent Asian, 37.0 percent New Zealand European and 3.7 percent Other. On the other hand, the Tasman region’s school roll in 2017 was 80 percent New Zealand European.

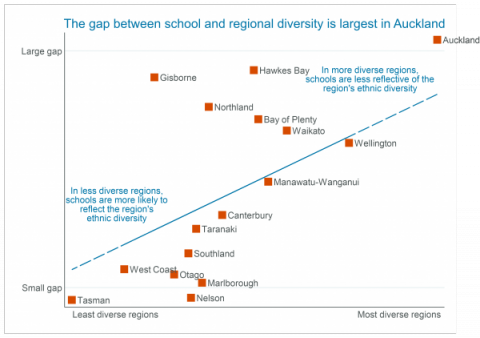

Auckland’s schools are not as ethnically diverse as the region’s school population

In 2017, the Auckland school roll was the most ethnically diverse region in New Zealand, but its schools, on average, did not reflect this diversity as much as schools in other regions. In general, as a region’s ethnic diversity increases, schools become less diverse compared to the overall diversity of the region’s school population. This would seem to indicate that in these regions ethnic groups are more clustered and not as dispersed across communities, compared with less diverse regions. The Tasman region has the least ethnically diverse school roll overall, but individual schools are as ethnically diverse as the overall regional population.

The exceptions to this pattern are the Gisborne, Northland and Hawkes Bay regions. These regions are not as ethnically diverse as the Waikato and Wellington regions, but their schools are less diverse compared with the overall region.

We measure the gap between school and regional ethnic diversity by comparing the ethnic composition of each school in the region with the ethnic composition of that same region overall. A value of one means every school has only one ethnic group and a value of 0 means each school has the same ethnic composition as the region it is in.

The chart above measures the gap between school and regional ethnic diversity by comparing the ethnic composition of each school in the region with the ethnic composition of the region overall.

Partnerships between parents, whānau and communities lead to better student outcomes

The New Zealand primary and secondary school roll is becoming more ethnically diverse. This can bring benefits as well as challenges for students and teachers. Schools will need to think about how they embrace and engage with different communities as schools become more ethnically diverse.

Effective partnerships between schools and parents, whānau and communities can result in better outcomes for students, in particular minority student groups. ERO has published advice about how parents and schools can build better partnerships between schools, parents, whānau and different communities to help support their students’ learning.

Our forthcoming publication Responding to Language Diversity in Auckland considers how well Auckland Schools are responding to the diversity of learners, and what works well for these learners and their whānau. In particular, ERO sought to identify:

- who are our language diverse learners in Auckland and how does diversity affect learning?

- how well are Auckland early learning services and schools responding to the increase in English Language Learners (ELLs)?

- effective practices of Auckland services and schools in responding to the challenges and opportunities for ELLs.

For further insight into what ethnic diversity looks like in schools, and its impact on language diversity, read the May Road School Case study: Walking in other people’s shoes, taken from our evaluation Responding to Language Diversity in Auckland which is expected to be published mid 2018.

Link to resources:

Strong connections between schools and parents and whānau are essential to accelerating the achievement of our kids, particularly those at risk of underachieving. This booklet helps parents, families and whānau to form effective relationships and educationally powerful connections.

Partners in Learning sets out what parents can expect from their child’s school and more importantly, how they can help their child do well at school. It describes what parents can do if they are concerned about their child’s learning and progress and what they can expect the school to do to help.

Culture, language and identity – video resource

This video, shot at McAuley College, highlights Domain 4 of the School Evaluation Indicators - Responsive curriculum, effective teaching and opportunity to learn. It shows how effective, culturally responsive pedagogy supports and promotes student learning.

For this article we used school roll data from the Ministry of Education, downloaded from the www.educationcounts.govt.nz

Case Study - May Road School: Walking in other people's shoes

Walking into May Road School, you first notice the cultural artworks and displays that cover the walls of the foyer and corridor. Next, you notice the flow of adults coming and going, greeting and chatting, and then the big smiles that warmly greet you from the children, adults and staff. An instant feeling of warmth and acceptance.

A sign “Welcome to May Road School” is proudly displayed and there are many other signs using the language of the children and their families around the school.

The staffroom is filled with people ‑ children reading, adults listening, parents gathering for the Incredible Years session, and plumbers replacing the hot water cylinder. It’s just after 9am and it’s business as usual at May Road School.

School leader

How do you and the teachers get to know the learners?

Knowing the learner is essential for all teachers to do – all good teachers do this; they know the learner, know the family and have a positive relationship with them.

This is our story of how we got to know our learners

Seventy‑five percent of our families are from the Pacific Islands. The Reading Together programme triggered a conversation about the parents’ experiences of education and aspirations for their children. It became clear that the usual data and information we collect provided some knowledge about the learner and their family. However, in order to truly tap into the potential of our learners we needed to develop a deeper knowledge and understanding of the families, their experiences, their culture, their background, and what it is like to walk in their shoes!

In 2010, a number of our teaching staff went to Tonga with some parents. We visited schools, talked with education officials and the initial teacher education organisations. The May Road School teachers had prepared lessons to teach children who spoke Tongan, not English. The teachers had to think about how they would do that. It was an experience that took them outside their comfort zone and put them into the place that our learners are often in.

It led to challenging conversations about our values, beliefs and assumptions, and what cultural responsiveness really means.

We asked ourselves several questions: “How did I feel in that situation? Is this how our learners feel? What am I doing in my classroom?”

We had conversations about reciprocity, cultural values, artefacts versus a true and genuine understanding and value of Pacific cultures and, other cultural groups. This forced the teachers to confront their own personal beliefs and actions, and their relationships with learners, their families and with communities. It challenged our assumptions and beliefs about some cultural practices such as why families give money to the church when they are struggling financially.

Some teachers were uncomfortable about having these deep discussions because it confronted their worldviews, but it helped to move things forward. It was truly an experience of walking in the shoes of our learners and their families.

What did you learn from that experience?

Learners do not have to be ready to come to us. We (schools, leaders and teachers) have to be ready for them. Culture is not about artefacts, culture is much deeper!

As a school leader, what knowledge, skills and dispositions are needed?

- Knowing that relationships are key and take time to build.

- To keep trying and to be resilient

- To share, be able to tell our stories, and allow yourself to be vulnerable

- To reach out even when it’s hard because parents’ experiences have not always been good

- To be ready to teach and learn too

- To be creative.

- To try something new, and if it doesn’t work then try something else. Don’t give up!

Everyone is here to learn and has a right to learn. Human Rights principles and values are embedded in this school ‑ respect all others, diversity and empathy, walking in others shoes, global citizens. A local school focussed on preparing the children for a global village. Where everyone is able to speak their own language and celebrate their own tradition, and where every child has a right to a voice, a right to learn and a right to be treated fairly.

Parents

What do you like about May Road School, and how are you supported?

My parents are living with us. They only speak Samoan, my husband and I speak English, at school our kids speak both English and Samoan. It’s important that our kids can speak to their grandparents in Samoan and when we go back to Samoa for holidays. May Road School encourages me to speak my home language; I feel welcomed and accepted here. They don’t judge me. I can ask for help. I am learning about how to help my children at home with their maths, their reading, and their learning. I come to the maths classes for parents and get to do maths with my kids. My children are making progress and I am too. May Road School ‘feels like a home.’ (Parent)

May Road School has the same values as our family and encourages cultural acceptance and respect for everyone. It’s a friendly and safe environment for my kids. (Parent)

What advice would you give another parent about language and learning?

I would encourage other parents to:

- Visit their child’s classroom

- Talk to their child’s teacher/s

- Value their own language/s, identity and culture

- Learn other languages

- Support their children to learn.