Summary

This case-study report features experiences of three Kāhui Ako (Community of learning). We share the strategies they used to create, build, and strengthen collaboration between schools and early learning services. These strategies give examples for others to consider.

This report is the third in a series of four publications, called ‘Collaboration in action’.

Read the first report, Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Collaboration to Improve Learner Outcomes

Read the second report, Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Working Towards Collaborative Practice

Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako in action

What is a Kāhui Ako?

A Kāhui Ako is a group of education providers. Each Kāhui Ako can include early learning services, schools, kura, and post‑secondary institutions. Together, a Kāhui Ako supports the needs of its children and young people by working with them, their parents, whānau, iwi, and the wider community.

Read more information on Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako on the Ministry of Education’s website.

We interviewed a range of people

The three Kāhui Ako we interviewed were Northcote, Ōtūmoetai, and Waimate. We spoke to:

- the lead principal of each Kāhui Ako

- iwi representatives

- learning support coordinators

- agencies outside of the education sector

- representatives of early learning services

- teachers in a range of roles.

Kāhui Ako had shared strategies for success

Overall, each Kāhui Ako’s education provider worked together and overcame challenges as they arose.

Sharing responsibility and focus

Each Kāhui Ako moved from thinking about ‘my school’ or ‘my early learning service’ to thinking about ‘our schools and early learning services’.

Leaders built trusting relationships between them to collect shared data and set shared goals relevant to all of their learners.

Leading with a learner focus

The most successful Kāhui Ako leaders had strong leadership and interpersonal skills. These leaders fostered collaborative decision-making.

Each Kāhui Ako focused on improving outcomes for learners. Leaders established models of practice which responded to the community context.

Building relationships with communities and iwi

Successful Kāhui Ako worked with the wider community. Two of the three Kāhui Ako built strong relationships with iwi. This supported their Māori learners.

Collaboration and resourcing supported the intended purpose of the Kāhui Ako’

Kāhui Ako recognised collaboration to share teaching practices can help support greater learner outcomes. Evidence confirmed teaching practice was a key focus of Kāhui Ako.

Leaders were strategic in how they used people, resources, and time. They worked hard to build trust and collaboration at different levels, and across the community.

Whole article:

Collaboration in practice: insights into implementationPromoting collaboration through Kāhui Ako

The opportunity to form and collaborate through Kāhui Ako was first implemented by the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) in 2014. The aim was to bring together schools, kura, early learning services, tertiary providers, and the wider community to raise learners’ achievement and strengthen education pathways.

The Ministry had previously promoted collaboration between schools through initiatives such as Building Evaluative Capability in Schooling Improvement, Kia Eke Panuku Building on Success, Extending High Standards Across Schools, and Learning and Change Networks.

Despite strong support for building collaborative networks, the New Zealand evidence base about the necessary conditions for effective collaboration is somewhat limited. To address this gap, the Education Review Office (ERO) initiated case study research to gather rich, in-depth information about the experience of schools, kura, early learning services, tertiary providers, and the wider community about the performance and operations of their Kāhui Ako. ERO’s framework, Building Collective Capacity for Improvement, built on international evidence on collaboration, and provides the backdrop for understanding how the experiences of Kāhui Ako compare with international evidence.

This ERO publication contributes to a series of four publications entitled Collaboration in Action. The report features the experiences of three Kāhui Ako and includes the strategies and approaches used to create, build, and strengthen collaboration between schools and early learning services to improve outcomes for learners. We recommend this summary is read along with two ERO companion documents published in 2017 and designed to support the development and evaluation of Kāhui Ako: Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Collaboration to Improve Learner Outcomes and Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Working Towards Collaborative Practice.

ERO’s approach focused on building collective capacity for improvement

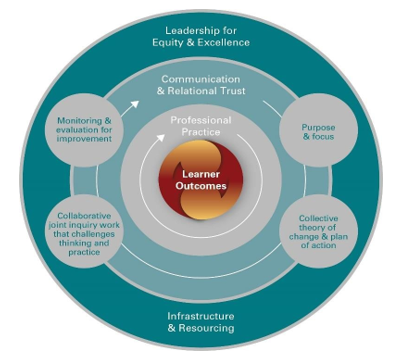

The ERO publication Communities of Learning | Kāhui Ako: Collaboration to Improve Learner Outcomes identifies key components important for building collective capacity for improvement. The framework (see Figure 1) brings together research findings about effective collaboration in education communities both in New Zealand and internationally. The case studies provide an important opportunity for ERO to contribute to the evidence base by examining collaboration in action.

Figure 1: Building collective capacity for improvement

This image is of increasing circles with Learner Outcomes at the centre. The next circle outwards is called Professional Practice with an arrow tracing its way around the circle. The next circle is called Communication and Relational trust. This also has the arrow tracing its way around the circle but it has four circles placed at intervals on the arrow. They are from right top, Purpose and focus, Collective theory of change and plan of action, Collaborative joint inquiry work that challenges thinking and practice and Monitoring and evaluation for improvement. The last circle which encompass all other circles is titled Leadership for Equity and Excellence.

The framework in Figure 1 identifies leadership, infrastructure, and resourcing as key enablers that promote effective collaboration. Effective leaders make sure resources are used appropriately, and supportive and inclusive structures are in place to allow members to work together. By facilitating collaboration, effective leaders build relational trust at every level of the community – critical to improving professional practice as well as implementing collaborative practices centred on learner outcomes.

ERO gathered information through case study interviews

ERO evaluators undertook case study interviews at each of the Kāhui Ako schools, or at a nominated host school. Evaluators initially met with the lead principal of each Kāhui Ako to discuss purpose and scope.

In addition, ERO spoke to:

- iwi representatives

- across-school teachers

- learning mentors

- within-school teachers

- teachers from across the Kāhui Ako, including those from particular learning areas

- regional Ministry of Education lead advisors

- learning support trial coordinators

- early learning services representatives on stewardship groups

- representatives of agencies other than education

- expert partners.

Interviews focused on these key areas:

- decision-making processes in setting up the Kāhui Ako

- purpose and focus of the Kāhui Ako

- description of collaborative processes

- perceived value of policy and service supports

- monitoring and evaluation

- leadership

- new teaching and leadership roles.

An interview guide provided focus for all interviews, with evaluators inviting respondents to share their reflections and observations about Kāhui Ako performance and operations.

Case studies from three Kāhui Ako are included in this report:

- Northcote

- Ōtūmoetai

- Waimate

Northcote Kāhui Ako

The Northcote Kāhui Ako, approved to establish in November 2016, is a collaboration amongst five schools (three primary, one intermediate, and one secondary school) and two early learning services that are philosophically aligned and close to each other geographically. The priorities for this Kāhui Ako are to build a community that inspires learning, and to create a cohesive educational pathway that delivers success for all learners from early childhood, through to schools, and beyond. In building consensus about valued outcomes that define and identify what ‘success’ looks like in the Northcote context, this Kāhui Ako was informed by key aspects of the ERO School Evaluation Indicators, The New Zealand Curriculum, Te Whāriki, Pasifika Education Plan 2013-2017, Tātaiako and the aspirations of their learners, parents, and whānau.

This image is a of six strips three are black and three are grey they are interlocked in a basket weave pattern. The very centre reads Akonga Learners. The three black strips read: Schools, Whanau/Family and Teachers. The three grey strips read: Across school leaders, Leadership team and Within school leaders.

Ahakoa he tino rerekē te ao o te kura ki te ao o te hau kāinga, ka tupu tonu ngā ākonga mehemea he maha ngā arawhata i waenganui i a rātau kia whakawhiti ai ki ngā huarahi wāia, ōtira ki ngā whenua o tauiwi

- Viviane Robinson 2011, translated by John MarsdenAlthough the worlds of school and home may differ greatly, students will thrive if there are enough bridges between them to make the crossing a walk into familiar, rather than foreign territory.

- Viviane Robinson 2011

Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako

The evolution of the Ōtūmoetai Community of Learning I Kāhui Ako maintained a strong focus on cross-cultural collaboration for educational transformation, innovation and developing strong pathways for learners.

The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako is made up of six primary schools, one intermediate school, one secondary school and one wharekura. In 2017, 5,641 students were enrolled in these schools. Of these approximately 1,300 were Māori students, and 65 were Pacific students. Students from the six contributing primary schools have an established pathway to the local intermediate school (88 percent of the students go on to the intermediate) and on to the local secondary (92 percent). There is also an established pathway from rūmaki classes at two schools to Te Wharekura o Mauao.

The inclusion of Te Wharekura o Mauao in this Kāhui Ako is noteworthy. This was helped by the existing relationships between the principals as members of the Tauranga Principals Association sub-group. The wharekura is located in the Ōtūmoetai geographic area and this was seen as an added advantage.

This is an image of a maori symbol. It's shape is of an elongated tear drop. The symbol is divided into four equal sections. They are from the top down:

section 1: Ko te ara poutama this section teaches us of the organic process of the learning and the adaptations that occur within teachers and the students whilst negotiating both the lessons and the learnings involved in the reciprocation, receiving and dissemination of information and knowledge.

Section 2: Ko te matata o te atua : this section is dedicated to the kaupapa and its participants. The use of the ara moana pattern highlights the importance of the journey of learning and the preparations that must occur before we set out to achieve our goals.

Section 3: Ko te mana o te whānau: this section is dedicated to each and every participant who comes in contact with the kaupapa. This magopare reflects the collective strength of schools, teachers, students and their families working towards mutal and shared goals.

Section 4: Ko te pitomata o te tauira: this region of the logo represents the untapped potential of students within our schools. It is our primary role as education providers to aim and assist at helping individuals to reach their fullest potential.

Homai ngā ture kia wetewetea!

Homai ngā tauira kia whakanuia!Show me the obstacles so I may tear them down, empower our children and praise them

Waimate Kāhui Ako

In 2015, the chairperson of the Waimate High School board of trustees (board) attended a New Zealand School Trustees Association (NZSTA) conference and heard the government’s Investing in Educational Success policy announcement. Together with the principal of Waimate High School, the chair set up discussions with other principals and boards of trustees in the district. This resulted in a coalition amongst local schools: at the start, the high school and three primary schools came together. Subsequently, a further three primary schools joined and another school expressed interest in being part of the Kāhui Ako. This growth in membership was a positive development for the Waimate community of learners.

The Waimate Kāhui Ako includes a range of deciles reflecting the mix of socioeconomic backgrounds learners come from. The district is characterised by:

- high transience (28 per 1000 in Waimate district compared to the national average of 4.7 per 1000)

- inadequate internet access in rural areas

- seasonal work and therefore seasonal workers

- a high proportion of students who travel by bus to their schools

- an ageing population

- an increase in Māori families

- an increase in migrant families.

This is the school picture of the reed. The words surrounding it are Waimate Kahui Aho Collaboration for success. Surrounding this is the Maori saying When the reed stands, alone they are vlunerable, but bound together they are unbreakable.

Ki to kohahi te Kaakaho ka whati

Ke te kaapuia, e kore e whatiWhen reeds stand alone, they are vulnerable, but bound together they are unbreakable

The case studies exemplify successes and challenges in early stages

These case studies show how it was possible to make significant progress in establishing the principles and direction of Kāhui Ako in the early stages of implementation. Each Kāhui Ako shared their successes and how they responded to the challenges encountered in their different contexts.

This report outlines key common factors of success. It also details aspects of individual Kāhui Ako that show specific models of practice. The thinking and actions described by these three Kāhui Ako give examples for others to consider, as they develop their approaches and structures.

The report addresses aspects of the Kāhui Ako that relate to the framework of effective collaboration in action:

- Getting started

- Establishing purpose and focus - using data to set achievement targets

- Leading collaboration

- Understanding what needs to change and making this happen

- Resourcing and infrastructure

- Monitoring and evaluating for improvement.

Examples of relevant practice from different Kāhui Ako are identified under each heading of the report. This approach highlights the relevance of different experience and learning that Kāhui had while setting up a new community of learning.

Getting started: building a collective sense of responsibility

Making the decision to form a learning community required shifts in thinking and practice on the part of the institutions involved. Deciding what the Kāhui Ako wanted to achieve was the most important factor since this gave clear direction to participants. Building a sense of collective responsibility for the success and progress of all children and young people in the community was paramount. The challenge for all those involved was to move beyond focusing on ‘my school’ or ‘my early learning service’ to ‘our schools and early learning services’.

Examples and stories from the three Kāhui Ako referred to in this report show the progress made in meeting this challenge.

Northcote

A strong commitment to work together to address a common set of issues drove the formation of the Northcote Kāhui Ako. While there was some previous history of collaborative work in the Northcote area, it was limited to one or two schools or early learning services working together on a common area of interest, including:

- transitions from early childhood to school between Northcote Community Baptist Pre-school and Willow Park School

- the My Learning Transition Project between Willow Park School, Northcote Intermediate School and Northcote College

- the Maths Learning Exchange between Northcote Intermediate School and Northcote College.

There was no history of collaboration involving all education institutions in the area as expressed in the principles of Kāhui Ako.

Who was involved?

The principal of Northcote College organised a meeting of all principals in the area. The discussions that followed indicated a strong preference for working towards strengthening education pathways for learners and their families. Initially, three schools and two early learning services (ELS) came together to form the Kāhui Ako. Over the next 12 months, another two primary schools joined. The ELS’ timely engagement is noteworthy and well aligned with the Kāhui Ako aspirations to strengthen the education pathway, and contributed significantly to building strong relationships between members of the Kāhui Ako. The boards of trustees were invited to guide the appointment process for the Kāhui Ako lead, and for the across-school teacher (AST) roles.

Ōtūmoetai

Making the decision to form the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako was based on the desire to collaborate for the benefit of children and young people across the community. For this Kāhui Ako, the decision to come together as a Community of Learning was reasonably straightforward and seen as a natural progression from working together as the Ōtūmoetai cluster of schools. Previously, the principals had cooperated as a sub-group of Tauranga Principals Association, and had also collaborated on a number of Ministry of Education initiatives, including for example, Extending High Standards Across Schools (EHSAS) (from 2008-2010), and shared professional learning and development (PLD) activities. These earlier collaborations established relationships at senior leadership and board levels across schools, and paved the way for the schools to come together to collaborate around the achievement challenges they identified as the Kāhui Ako.

In spite of their established relationships, the conversation between the tumuaki of the wharekura and other principals during the formative stages of the Kāhui Ako is worth noting. The tumuaki saw the value of being part of the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako, and set expectations for authentic collaboration. They identified two conditions (placed before the other principals) that might have impeded collaboration: they ‘did not want to do all the giving’ (‘dial a pōwhiri’), and they did not want to be the ‘salad dressing’.

Who was involved?

At the start, the principals were the prime movers in establishing this Kāhui Ako and led discussions with Ministry lead advisors about the formation and focus of the Kāhui Ako. Subsequently each school’s senior leadership team and board representatives contributed to this early Ministry engagement, and, as engagement broadened, engaged with union and iwi representatives.

Following the endorsement of the Kāhui Ako, each school led its own process for involving staff and the wider community. All stakeholders interviewed remarked that the process used to deepen engagement at the Kāhui Ako level was thoughtful and respectful of the different contexts of the school communities.

Efforts were made to deepen the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako partnership with iwi (beyond representation in governance structures), and aligning Kāhui Ako aspirations with iwi aspirations and strategies. The Ministry timelines for setting up Kāhui Ako were identified as impeding Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako aspirations for more authentic engagement with iwi during the early stages, leading to frustrations on all sides. However, at the time this case study was undertaken, these issues were gradually being worked through.

Waimate

In 2015, the chairperson of the Waimate High School board of trustees (BOT) attended a New Zealand School Trustees Association (NZSTA) conference and heard the government’s Investing in Educational Success policy announcement. The board chairperson and the principal of Waimate High School set up discussions with other principals and boards of trustees in the district. With support from Ministry regional staff and NZSTA, a coalition was formed. At the start, the secondary and three primary schools came together. Principals and board chairs acknowledged there was early resistance from some. A general suspicion around the underlying intent of the policy, including the Ministry’s initial messaging suggesting Kāhui Ako were compulsory. However, this changed with a further three primary schools joining and another school expressing an interest in being part of the Waimate Kāhui Ako. This growth in membership was a positive development for the Waimate community of learners.

Who was involved?

The Waimate High School principal and board chair played a critical role in establishing this Kāhui Ako. Despite not yet having an official role, their passion and drive was instrumental. Initially, the leadership demonstrated by the secondary was seen by some as a ‘takeover’; however, these sentiments were put to rest as implementation progressed.

The schools in this Kāhui Ako had already worked together on a number of professional, cultural, and sporting initiatives over the years. Prior relationships helped overcome a competitive mind-set and gave focus to raising student achievement across the schools. The formation of the Kāhui Ako cemented what was to become a legacy of cooperation, and acted as a catalyst to formalise systems and processes aimed at strengthening working practices as a Kāhui Ako. The Kāhui Ako was formally launched in the community through a shared lunch, and was followed by a joint teacher only day at the start of Term 1, 2017.

Establishing purpose and collective focus: setting achievement challenges

Achievement challenges are shared goals identified and developed by a Kāhui Ako based on the needs of its learners. Achievement challenges are usually accompanied by an action plan for improvement. Identifying the ‘right’ challenges is crucial to enabling the system transformation desired through Kāhui Ako. These Kāhui Ako were in the early stages of setting and monitoring progress towards achievement targets.

This process was not straight forward for Kāhui Ako for several reasons. Where schools already shared information and were confident of the quality of achievement information, setting targets was relatively straight forward. However, in some cases, teachers and schools were reluctant to share information with others. As the leaders built trusting professional relationships amongst participants and kept a clear focus on the purpose of collecting and using data, this reluctance lessened.

Northcote

The process of establishing a collective focus in the Northcote Kāhui Ako took time. Twelve months and 12 drafts after this process began, the achievement challenges were endorsed. Although the Kāhui Ako members found it frustrating, it enabled them to learn more about each other’s context, motivations, and challenges.

Finding the focus

Through systematic analysis of 2015 achievement data, school leaders looked at trends and patterns to address achievement challenges of boys, Māori learners, and Pacific learners in reading, writing, mathematics (Years 1 to 8), and NCEA Level 2. The process of identifying these challenges, however, led to a shared realisation that improvement of teaching and learning practices lay at the heart of achievement. Consequently, the Kāhui Ako determined this improvement as their focus, from which success for learners in their community would emerge.

Ōtūmoetai

Working collaboratively, Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako leaders and trustees were eager to identify areas where they could make a real difference for learners, and focus some of their best teachers and leaders on these areas. An initial set of achievement challenges emerged from discussions amongst the principals. These challenges were thoroughly investigated and interrogated using different data sources including:

- each primary school’s national standards and Ngā Whanaketanga Rumaki Māori data for 2013-2015

- each secondary school’s NCEA data

- each school’s in-depth data on student achievement

- Ministry data on current special education caseloads

- the Education Review Office summative report for the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako

- a special Ministry report on pathway data from early learning services on participation to NCEA achievement.

Combining multiple sources of empirical data with professional knowledge about the challenges faced by learners in and across their schools allowed principals in this Kāhui Ako to identify an agreed set of common challenges. They then began developing relationships across the learner pathway, by bringing together different voices when establishing collective purpose, focus, and achievement challenges for their Kāhui Ako.

The value of clarifying purpose

The achievement challenges provided an anchor for galvanising the Kāhui Ako, and the process of setting the challenges also played a role. Strategies to clarify the purpose and focus of the Kāhui Ako provided the foundation for further investigation and collaborative sense-making helped members of a steering committee to develop priorities for action. Members of the Kāhui Ako had to consider carefully what was needed to bring about the shifts that would make the most difference. This resulted in a small number of targeted activities: collaboration around strengthening pathways (for example, a shared focus on oral language); promoting cross-cultural collaboration (for example, a shared commitment to working purposefully with the wharekura); and opportunities for innovation (for example, implementing a learning support trial). The focus on oral language as an achievement challenge, ensuring a voice for ELS in the steering committee, allocating Kāhui Ako resources to focus on the challenge, and inviting ELS to be a part of PLD are clear signals of commitment to develop and connect along the educational pathways within the Kāhui Ako.

An issue to address

The Kāhui Ako lead characterised the Ministry’s Kāhui Ako implementation framework as ‘narrow’. This perception caused tension with the aspiration of their Kāhui Ako to take a broader view of the achievement challenges they wanted to set. This Kāhui Ako was asked to resubmit its achievement challenges to fit with ‘Ministry’s requirements’. Clearer guidance about how raising achievement levels in literacy and mathematics can act as a precursor to students achieving in the broader curriculum may have helped overcome frustrations.

Waimate

Reaching collective agreement

Delays in having achievement challenges endorsed were a source of great frustration for Waimate Kāhui Ako, and as a result it lost momentum and energy. By the time endorsement was gained, there were changes in leadership with four new principals appointed (all first-time principals). Socialising them into the discussions and focus took time. In spite of these challenges, the collective vision of the Kāhui Ako is understood by all and shared proactively with members of the wider community.

Starting with each school in the community

The process for identifying a collective focus began with each school investigating student achievement in their particular school context. This was described by all as a challenging but worthwhile exercise. Using the data gathered by each school, achievement challenges were identified for mathematics, writing, reading and an NCEA leaving qualification. Within each challenge, the Kāhui Ako decided to target students who were achieving below curriculum expectation, as improving their outcomes would help them access the curriculum more effectively. While everyone endorsed this focus, they also made an explicit commitment to track progress against the identified challenges. This process was considered far more meaningful, and ensured the Kāhui Ako efforts remained student and outcome-focused.

Establishing a clear process for data analysis

There was a growing recognition of the need to establish effective structures and processes for ongoing analysis of achievement and progress data. High expectations around the quality of data analysis led the Kāhui Ako lead to work with an expert partner and statisticians from NZCER to explore ways of analysing the data gathered through the literacy learning progressions and national standards. They developed a common spreadsheet for recording schools’ overall teacher judgements (OTJs) relating to the national standards. Schools included norm referenced data through their student management systems (SMS). For some, this was the first time they had used their SMS for data recording and collation. Teachers and principals reported more openness about sharing the data at different levels within the Kāhui Ako and presenting the analysis to the stewardship group annually.

Refining the system

As a next step, the Kāhui Ako was exploring the development of a tool to measure and record finer grade shifts in student achievement. It is also looking at using the Progress and Consistency Tool (PaCT) across the Kāhui Ako.

Leading collaboration: the Kāhui Ako lead is critical to success of collaboration

Inclusive leadership is a characteristic of successful Kāhui Ako. Leaders have a crucial role to play not only in developing a compelling vision, but also in implementing that vision in a way that genuinely includes the perspectives and aspirations of participating institutions and the community, particularly learners, parents, and whānau. The role of the Kāhui Ako lead is critical to the success of this collaborative endeavour. The ability of leaders to motivate, energise and progress collaboration amongst all partners requires clarity of purpose and direction. Supported by the expert partner and the Ministry, the Kāhui Ako lead strives to bring about change through influence and deliberate acts of facilitation that leverage external and internal expertise as needed.

Successful Kāhui Ako leaders in this study demonstrated high levels of educational leadership and interpersonal skills. They understood that the effective formation and development of Kāhui Ako depended on shared, non-hierarchical decision making. Success factors in these three Kāhui Ako included establishing a shared understanding of good practice for:

- forming partnerships

- building trust when sharing data and strategies for learning

- using resources in the best way.

Success factors also included a systematic, collaborative focus on improving the progress and achievement of learners, and willingness to evaluate and respond to the results of evaluation to continue to improve practice and outcomes. Leadership success is evident in each of these Kāhui Ako.

The lead role

Appointing a lead in each Kāhui Ako was relatively straight forward. This role was usually taken by a prime initiator in forming the Kāhui Ako, who had taken a lead role in earlier cross-community networks. The lead already had the confidence of Kāhui Ako colleagues and had developed rapport through the formation phase.

A Kāhui Ako lead needs to:

- work with different groups at different levels of the system

- engage with the Ministry and other Kāhui Ako leads

- participate at different fora organised by the Ministry

- provide direction and leadership to the across-school teachers

- work with expert partners.

This has stretched their educational leadership and interpersonal skills.

Northcote

Building and sustaining collaboration

The leadership displayed by the Northcote Kāhui Ako lead and that of the stewardship group, was critical to creating and sustaining the collaboration. Collaborative and inclusive leadership made sure appropriate people were brought together in constructive ways. Early learning services (ELS) have been, from the beginning, particularly positive about their inclusion and role in the Kāhui Ako. Ongoing efforts to keep all ELS in the area updated about progress is seen as a reflection of the commitment to creating pathways for learners in the community. The Northcote Kāhui Ako lead played a critical role in fostering collaboration and building relational trust at each level of their community. Establishing the Kāhui Ako enabled school leaders and teachers to step up and rekindle their passion and enthusiasm for the profession. It also provided new and varied challenges for experienced principals.

Ōtūmoetai

Strong relationships

The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako showed that strong relationships and partnerships across diverse actors can build support and legitimacy for collaboration. ERO noted the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako was deliberate in both developing new partnerships to deepen its understanding of the issues, and drawing in different skills, perspectives, and expertise to develop a multi-pronged, community-wide approach to collaboration. The leader worked to bring about change through influence and through careful acts of facilitation to leverage external and internal expertise as needed. The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako lead’s role was seen as the strength of this Kāhui Ako and was endorsed by all participants.

Waimate

Collaborative enquiry

At the start of the process of establishing the Waimate Kāhui Ako, the leadership demonstrated by the secondary school was seen by some as a ‘takeover’. These reservations were put to rest as implementation progressed. Waimate Kāhui Ako provides an example of the value of inclusive and influential leadership:

“Two years ago, the idea of our schools working and thinking together was absent. Now there is a shift in our language from ‘my kids’ to ‘our kids’, ‘Waimate kids’.”

Lead principal

The Kāhui Ako leadership was well connected, well aligned, and committed. The lead principal played a critical role in fostering collaboration and building relational trust at each level of the Kāhui Ako. The leadership role provided an important opportunity for school leaders to step up, and rekindled their enthusiasm for the profession through new and varied challenges. The commitment displayed by the Waimate Kāhui Ako lead contributed significantly to creating and sustaining this collaboration. The lead’s foresight and influence in the initial stages was critical in transforming the aspirations and vision of this Kāhui Ako into a reality.

Role of AST and WST: new roles to support Kāhui Ako

Two new roles are critical to the success of Kāhui Ako: the across-school teacher (AST), and the within-school teacher (WST). In the majority of instances, it took time for these positions to be filled.

The ASTs are the lynchpin in the Kāhui Ako programme, and it was important to make sure the right people with the right skills were appointed. This teacher acts as the bridge between school leaders and classroom teachers. The teacher is required to teach 50 percent of the time, so their knowledge and expertise is current and credible with school leaders and teachers alike. It has taken time for the Kāhui Ako to come to terms with these roles and negotiate ways of working across the Kāhui Ako so the focus of these roles is on achievement objectives.

ASTs viewed these roles as challenging and rewarding, both professionally and personally. They had the opportunity to observe leadership in action, and step into leadership themselves while maintaining a focus on teaching and learning. Other teachers had begun to see the contribution and added value of these roles, which lessened initial resentment about additional remuneration. It has allowed teachers to act as practitioners of research, inquiring into and working on issues likely to have the most influence on learning across the education pathway.

WSTs acknowledged some initial reluctance and concern that stemmed from lack of confidence and negative perceptions relating to the role’s workload. Since this early phase, teachers have become better informed about expectations and responsibilities, particularly about the initiative and leadership required to drive change within their school. Some concern remains about the size and function of the role and some WSTs have sought greater clarity about the direction of their work.

Understanding what needed to change and making this happen

What key actions led to positive outcomes?

Each of the three Kāhui Ako maintained a central focus on improving outcomes for learners. Leaders took different approaches to establishing models of practice. They were responsive to the community context and looked for relevant and appropriate ways to establish outcomes, collaboration, and inclusive structures and practices.

Northcote

A clear, well-developed operating model to support collaboration

Participants in the Northcote Kāhui Ako were deliberately casual in their conceptualisations of the structures and procedures for their community. Initially, their main structural arrangement to establish the Kāhui Ako was a stewardship group that included all principals, deputy principals, school and ELS leaders, as well as the regional Ministry representative. This group met monthly. It acted as a steering committee to respond to emerging Kāhui Ako-related issues, and as a professional learning community for members to support and facilitate their own inquiry. The ASTs were invited to come to the stewardship group to report on their work, and also for guidance and direction. Each individual member school on the committee was responsible for reporting back to their board of trustees about the progress of the Kāhui Ako. The annual report was prepared by the lead principal and distributed to all school boards and governance groups across the learning community. Over time, the stewardship group took on the governance role, while the Kāhui Ako lead, ASTs, and WSTs operationalised the work.

In the first year of operation, the Kāhui Ako lead met with ASTs and WSTs fortnightly to find ways of working together, and with the Kāhui Ako schools and ELS to support teaching as inquiry, professional learning, and/or student learning projects. For example, the ASTs and WSTs were encouraged to read papers and discuss them in relation to their aspirations in their own contexts (e.g. Helen Timperley’s paper on Spirals of Inquiry; ERO report Teaching strategies that work- Mathematics). As a result, this group served as a professional learning community for the Kāhui Ako.

Ōtūmoetai

An agenda for change

Successful collaboration requires all participants to have a shared vision for change, including clearly defined objectives and solutions. Collaboration often breaks down when participants think they are working on the same issues, but find out this is not the case.

Collaborative practices established through a long history of working together helped the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako to establish and share an agreed agenda for change early on. A group of school leaders, for instance, supported by their boards, undertook awareness-raising activities in their respective schools and the wider community. Focus groups, community hui, and information evenings were used to develop a road map and vision for change, and galvanise community efforts around the vision.

The inclusion of boards’ representatives in setting the agenda for Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako was a shift from earlier collaborative efforts as a cluster. Participants acknowledged that in the past there was limited or no involvement of boards in school clusters. Since the establishment of the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako, principals have built more meaningful relationships with school boards and with a variety of stakeholders, and created a stronger role for them in governance and management of the Kāhui Ako. More generally, the Kāhui Ako leadership facilitated discussion and debate about strategies for driving change by always bringing different voices together.

Focusing on a small number of high-leverage activities

Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako had to choose which actions would most benefit student achievement. This resulted in the identification of a small number of targeted activities:

- collaboration to strengthen pathways (for example, a shared focus on oral language)

- cross-cultural collaboration (for example, a shared commitment to working purposefully with the wharekura)

- innovation (for example, implementing a learning support trial).

Creating a clear operating model

Effective structures that support implementation of the agenda for change is at the heart of a successful collaboration. The elements of the operating model developed by Ōtūmoetai and discussed in this section include:

- creation of inclusive structures to support the collaboration

- use of deputy principals as learning mentors

- effective allocation of across-school teacher (AST) and within-school teacher (WST) resources.

Kāhui Ako decisions regarding the structures reflect their aspirations to be inclusive and leverage their internal and external expertise to address the challenges.

Creating inclusive structures to support collaboration

Participants in Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako quickly acknowledged the need to create a structured process for effective decision making. In its early stages, the collaborative process appeared ad hoc, and the dedicated time needed for the work was not anticipated. Participants recognised that early attempts at collaboration had failed because supporting infrastructure was not in place, and that collaboration takes time.

To counter these issues, participants agreed to establish a steering committee with overall responsibility for governance and management of the Kāhui Ako. Membership of the steering committee signalled to the community the Kāhui Ako intent and aspirations for change. The steering committee included principals of all member schools, learning mentors (deputy principals – discussed below), Ministry regional lead advisors, representatives from early learning services (ELS), iwi representatives, and ASTs. The diverse membership of the committee was inclusive, focused members’ attention to maintain a sense of urgency, and mobilised stakeholders without overwhelming them. The steering committee was able to frame discussions to present opportunities as well as challenges, and allowed participants to navigate differences thoughtfully and build trust and empathy amongst participants.

In addition, Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako established four advisory/working groups to support specified work areas and achievement challenges. Advisory group membership included two to three senior leaders (including the learning mentors), and possibly a principal working with ASTs. This created teams of five to six people focused on the achievement challenge for their year levels, thus effectively acting as a ‘leadership’ team for that area of work. Members of the working groups also made sure there was good ‘flow’ between areas of work across the Kāhui Ako.

These operational structures are supported by clear terms of reference specifying mandate, roles and responsibilities. This approach has maintained momentum at different levels of the Kāhui Ako and served it well.

Deputy principals as learning mentors

The Kāhui Ako model requires ASTs to spend 50 percent of their time in classrooms.2 This means many deputy principals (DPs) who are leaders of learning in their schools are not able to meet the prerequisites. While the intent underpinning the policy was understood, the remuneration associated with the AST roles upset the dynamics amongst staff and undermined the pedagogical leadership DPs had demonstrated over the years. In some instances, those appointed to the AST roles struggled to lead the learning of adults across the Kāhui Ako.

“It’s about not putting the ASTs in front of others till they are ready. It would not be a responsible thing to do.”

Lead principal

The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako decided to appoint their DPs as learning mentors, with a clear mandate to support and build the capacity and capability of ASTs. ASTs are leaders drawn from participating schools to engage with other leaders and ASTs. However, DPs are most likely to be unit holders and in leadership positions in their own schools. As learning mentors to the ASTs their role was “to guide/mentor the work of the Kāhui Ako in their area of work”. As illustrated below, the ASTs have mostly valued the contribution made by the learning mentors, and believe their active engagement was critical to building AST effectiveness.

“We have curriculum expertise but we don’t have much leadership expertise. The learning mentors are helping to bridge that gap strengthening our overall growth as leaders.”

“The learning mentor helps to strengthen the credibility of the ASTs; they have the ability to influence and have done that on many occasions.”

The innovative use of the skills and expertise of the DPs as learning mentors allowed this Kāhui Ako to value the ‘unsung heroes’ in the system who appeared to some to be displaced by the Kāhui Ako model.

Innovative inclusion of learning support expertise

One of the underlying intentions of the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako model was to help schools use the power of collaboration to innovate teaching and learning approaches. The learning support trial of this Kāhui Ako is an example of this. Dissatisfaction with the responsiveness of the learning support service, combined with the need to give every child the opportunity to access the curriculum at their level, led the Kāhui Ako to consider participating in a learning support trial. The Kāhui Ako provided a strong voice in discussions with the Ministry that resulted in a new solution to a shared problem. The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako seconded one of their senior special education needs coordinators (SENCO) to the Ministry at 0.5 FTEs to work across three Kāhui Ako in the region. Synergies were created through the following actions:

- schools working together collaboratively to share data on students with additional needs and seeing them as part of the Kāhui Ako community of care

- establishing one register in each school to capture consistent information for the Kāhui Ako register, and to monitor progress against actions

- providing flexible options for family and whānau to seek support and advice (as opposed to a referral service)

- developing an electronic student plan where all information and progress could be captured

- building relationships with key people in agencies and services aligned with the culture of Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako.

“Often as a single school, you don’t have the strength of numbers and you don’t often have the relationships; so it takes time to get things done. But as a Kāhui Ako, we represent the voice of X number of learners and teachers. This gives strength to our voice and we get heard.”

Waimate

Creating inclusive structures to support collaboration

The intentions and principles underpinning the Waimate Kāhui Ako were well supported, and genuine collaboration centred on shared responsibility for all children and young people. Participants acknowledged it would not be possible for individual schools to undertake the work being done in the Kāhui Ako, such as the creation of the joint operational guidelines or access to professional learning and development (PLD). Access to PLD was particularly relevant for small schools as they would not be eligible for the resource.

A clear operating model

Leaders understood that a clear operating model with well-defined structures and procedures was necessary for the collaboration to function effectively. This operating model provided clarity about:

- decision-making processes

- roles and responsibilities

- how information and resources would flow between members

- how widely power and influence was distributed among members

- how members would collaborate

- how the community would mobilise around change in Kāhui Ako leadership, staff turnover, or a change in the judgement resulting from an ERO review – acknowledging change happens as the Kāhui Ako matures and develops.

Leaders were very deliberate in the conceptualisation and implementation of structures and procedures for Waimate Kāhui Ako. The structures developed in consultation with principals and boards’ representatives actively promoted cross-school collaboration and joint work. Structural arrangements to operationalise the Kāhui Ako include:

- a stewardship group operating as a sub-committee of each board with two representatives, the principal and a trustee from each school’s board. This was set up at the outset. Their work is guided by a stewardship framework that clearly articulates the scope of their mandate and the principles underpinning their operating model, including how conflicts and disputes between Kāhui Ako members would be resolved. The stewardship group holds responsibility for appointing the Kāhui Ako lead, ASTs, and WSTs. The stewardship group also offered trustee training sessions to members of the board of all schools to build collaboration at board level. At the time of ERO’s visit, the stewardship group was considering adding a member of the rūnanga to the group to strengthen engagement with parents, whānau, and the wider community.

- a syndicate structure with each WST leading a cross-school syndicate. Three syndicates were set up to cover Years 1 to 3, Years 4 and 5, and Years 6 to 8 to support collaboration between teachers from different schools teaching at similar year levels. The syndicates meet twice a term and the syndicate leads (working group) meet one week earlier to plan, ensuring the meetings are well run, organised, and focused. This also ensures all schools are benefitting from the extra resources. The syndicates were given a clear mandate for leading learning across the Kāhui Ako. The successful use of the WSTs as across school roles is a unique and innovative response to the resource allocation for this Kāhui Ako.

- a working group that includes Kāhui Ako leadership and teaching roles. This makes sure the focus and principles of spirals of inquiry are used to inform and drive decisions.

- a management group that includes all principals. This group meets twice a term and serves as a platform for collegial support, Kāhui Ako management, and PLD - particularly for the first-time principals in the Kāhui Ako.

Working with the wider community

What steps did Kāhui Ako take to strengthen participation?

Successful Kāhui Ako understood the necessity of working with and across the wider community to clarify expectations and develop desired approaches to improving educational outcomes for children.

Northcote

Bringing the community together

The Northcote Kāhui Ako acknowledged the importance of recognising parents, whānau and community as key influences on children’s learning, wellbeing and self-efficacy. This led to a commitment to build and share learning strategies with parents, whānau, and the community to support learners’ achievement and success. The vision for this endeavour was described as:

- working together to identify agreed values, student strengths, learning needs, and responsive learning strategies

- developing a variety of strategies to communicate with and engage parents and whānau in activities to improve learning

- recognising, respecting, and valuing diverse identities, languages, and cultures of the school community.

Strong relational trust

This vision, combined with strong relational trust in the Northcote community, laid the foundation for effective operations from the outset. The action plan, developed in 2017, to implement their vision began with getting to know their kura and ELS and collaboratively investigating the values and beliefs that teachers, parents, and learners hold about teaching and learning. The end-of-year report shows significant progress in implementing an action plan, and a renewed effort to address issues identified through noticing, investigating and collaborative sense-making processes.

The process of knitting together the vision of success of schools, teachers, and whānau for their learners with the support of the three roles – lead principal, AST, and WST - drives Northcote Kāhui Ako efforts and reaffirms their commitment to act as a professional learning community.

Ōtūmoetai

Relationship building with early learning services

Participating in the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako led participants to become more aware of the need to work across educational pathways to meet the challenges of raising achievement. This led to more active engagement with ELS, and finding ways to involve them in the work of the Kāhui Ako. The Kāhui Ako lead played an important role helping to overcome some of the participation barriers ELS face. Key enablers that led to fostering strong relationships with ELS included:

- a commitment to making participation work, reflecting a belief in the intrinsic value collaboration offers to learners and their whānau

- creating value for ELS to enable them to overcome barriers linked to resourcing. PLD around oral language (an achievement challenge) was scheduled to ensure ELS leaders and teachers could attend. High attendance at the PLD workshops from these leaders and teachers, and plans to bring the PLD facilitator into the ELS to observe and model teaching strategies, enhanced the value of Kāhui Ako for them. As noted by the ELS’ representative, participation in joint PLD is “bridging the ECE-school divide”.

- ELS representation on the steering committee to enact authentic and meaningful engagement. The Kāhui Ako explicitly requested and accepted nominations from the ELS for two representatives to be on the Kāhui Ako steering committee, and this broke down barriers and created the trust required for collaboration.

Other agency support for students

The relationship established with the local District Health Board is another example of innovation fuelled by the collaboration. The Bay of Plenty District Health Board and the Ministry’s Bay of Plenty Waiariki region was looking to pilot a school-based mental health service in a Kāhui Ako. The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako was ideal as it includes settings along the education pathway from ELS through to secondary level. The decision to be a part of the pilot was made easy as the Kāhui Ako had already identified student wellbeing as a key achievement challenge for all participants. Having a dedicated registered mental health professional working with children and young people across the Kāhui Ako, as well as supporting whānau and teaching staff to understand mental health and other related issues that may affect a child’s learning, was seen as a positive by the schools. Participants also acknowledged this was possible only due to the collaboration – “Being part of the Kāhui Ako is empowering us to tackle some of the bigger challenges impeding learning”.

Building relationships with iwi

Investigating the extent to which Kāhui Ako have engaged with iwi in determining achievement challenges and finding solutions is essential for two related reasons. Firstly, one policy intent of Kāhui Ako is to accelerate progress and raise achievement for all students, particularly Māori students who are more likely to be underserved by an education system that does not yet provide equity and excellence for all students.3 Secondly, in the development and implementation of Kāhui Ako, the Ministry and schools have an obligation to uphold the Treaty of Waitangi responsibilities of partnership, participation, and protection. These obligations are heightened when the purpose of collaboration is to accelerate progress and raise achievement for Māori learners.

Northcote

The Northcote Kāhui Ako acknowledged that they had minimal engagement with iwi up to this point of their journey. This was predominantly due to a lack of awareness and confidence around how to meaningfully engage with iwi, rather than a desire to be exclusive. Moving forward, the Kāhui Ako is eager to develop resources that capture local history to build a deeper understanding of the socio-cultural context of their community.

Ōtūmoetai

Iwi participation

All schools in the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako fall within the Ngāti Ranginui iwi rohe. The majority of students are drawn from all three iwi in Tauranga Moana: Ngāti Ranginui; Ngai te Rangi; and Ngāti Pukenga. The Kāhui Ako provided an opportunity to involve iwi in accelerating educational outcomes for students in the rohe. Iwi were invited to be on the steering committee and contribute to governance and management. However, both sides recognised the potential for constrained involvement because iwi are not resourced as Kāhui Ako participants. The Kāhui Ako lead, together with other steering committee members, is looking to address the capacity issues faced by iwi to make sure their engagement is sustainable. The Kāhui Ako actively participates in iwi liaison meetings organised by the Ministry to continue to discuss how authentic, and purposeful engagement with iwi can be achieved. Iwi believe they have a strong contribution to make.

Building a relationship with the wharekura

While prior relationships existed between the principals in this geographic area, the engagement and active participation of the wharekura in the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako represents a significant shift. The wharekura motives for joining the Kāhui Ako were clear. At a strategic level, it offered an opportunity to influence issues of Māori achievement in their area. At a practical level, the tumuaki wanted to find ways of accessing resources in science and mathematics for NCEA Level 2 and Level 3 students. On both fronts, the benefits of the collaboration were felt across the Kāhui Ako.

Typically, the wharekura primary relationship was with another secondary school who was not a member of the Kāhui Ako. Joining the Kāhui Ako enabled the wharekura to access the skills and expertise of the science and mathematics teachers from Ōtūmoetai College. Conversely, the staff at Ōtūmoetai College had an opportunity to improve their understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy – teachers’ world views of teaching in Māori-medium settings expanded beyond what any PLD could offer them, and they have felt privileged to be given this opportunity. In addition, some of the teaching and pastoral care strategies used in wharekura were finding their way into Ōtūmoetai College, which has a significant number of Māori students. This cross-fertilisation could not have been possible without the supporting structure of the Kāhui Ako. As a staff member from the wharekura commented:

“As a result of our engagement in the Kāhui Ako, we are in a position to offer technical subjects to our learners. We are fulfilling our responsibility to offer the best opportunities for our mokopuna.”

“Our relationship with the college has undergone huge changes. They now come to the wharekura and can see we do things differently. They can see that the pedagogy we use for teaching is different and they take that understanding back to their own students.”

Waimate

Partnering with iwi

The Waimate Kāhui Ako lead, as the principal of the secondary school, had established relationships with the staff at the rūnanga at Waihao and had collaborated with them in the past. The lead approached the rūnanga seeking their support and engagement in the Kāhui Ako. They were involved from the beginning and contributed to the discussions around the logo and achievement challenges. The rūnanga viewed the decision to use the raupo reed as a symbol of their aspirations as an expression of the Kāhui Ako’s commitment to improving Māori student wellbeing and achievement. Specific actions include Ngai Tahu-led plans for a consultation hui with the parent community across all schools in the Kāhui Ako; the translation of the Kāhui Ako charter into te reo; and plans to hold a joint hui on cultural responsiveness, led by the rūnanga and involving all Kāhui Ako schools’ teachers.

While it is still early days, both the Kāhui Ako lead and the marae elder have seen the potential for working together to build cultural understanding and a local curriculum. They have proceeded slowly in this regard. The fact that there was originally no iwi or rūnanga representative on the stewardship group was noted and an iwi representative was appointed to the group.

Acknowledging the cultural history of Waimate

The choice of raupo reeds as an identifying image in the logo is particularly appropriate and well captured in the whakataukī of this Kāhui Ako. This particular type of raupō waka is used for the mōkihi (raupō canoe) – this is indigenous to New Zealand and to the Waimate area. The technology is handed down from the original Waitaha people through the Kāti Māmoe migration, then later Ngāi Tahu and finally Takata Pora. The local Hayman family was reputed to be excellent mōkihi makers in their day. Locally the technology was retained and passed on to the current generation of local Waihao Māori and the Te Maihāroa whānau.

The importance of this technology in the development of the district and its use by all succeeding inhabitants resulted in a gift of a mōkihi made by the Te Maihāroa whānau on the 150th celebration of the Waimate District and it now sits outside the Waimate District Council building.

“To see this principle reflected in the logo of the Waimate Kāhui Ako resonates in such a positive way. It gives a real sense of excitement about the potential and future of the Waimate Community of Learning and learners in our community.”

– Wendy Heath, Waihao Marae

Extending collaborative teaching practice - innovations

A major component of the development of Kāhui Ako has been the emphasis on collaboration to improve outcomes for learners through changes in teaching practice. Effective collaboration can be characterised as frequent sharing of knowledge and practice among participants, with the aim of addressing a set of common challenges. Use of data and inquiry identified teaching practice as a key focus area for innovation and professional sharing to raise student achievement across communities, and this has occupied much time and planning for all Kāhui Ako.

Northcote

Professional learning challenges

Creating opportunities for professional learning and sharing has been important in the Northcote Kāhui Ako. Inspiring and sustaining this focus, however, has been more challenging. Sentiments like “the across-school teachers should be telling teachers how to change” reveal an expectation of a more active change process among the within-school teachers (WSTs) and other teachers in the Kāhui Ako. Be that as it may, the stewardship group and ASTs preferred to create a platform for collaborative inquiry and work that aimed to challenge thinking and practice. Effective collaboration was characterised by deep and frequent sharing of knowledge among participants with the aspiration to bring about enduring change. As the WSTs and other teachers embarked on collaborative inquiry, they developed a more in-depth understanding of what needed modification and took the initiative to bring about change in their own contexts. They connected within the network and look outwards to gain new knowledge and insights to determine what was needed to address the challenges their learners face. Such inquiry processes resulted in the realisation that there was “no silver bullet”; that change can only come about by unpacking and adjusting existing beliefs and theories held by teachers, parents, and students.

“This is hard work. We are willing to be patient and deliberate about it. We are going about it systematically and it will take some time to percolate down to all teachers.”

Across-school teachers

The challenges were evident in the results of a survey of teachers the Kāhui Ako conducted in Term 3, 2017. The findings show over half responded with either ‘not well’ or ‘not at all well’ to questions about their perceived value of participating in the Kāhui Ako and/or how well the Kāhui Ako was supporting their capacity for inquiry. In response to these findings, a roadshow was undertaken. The Kāhui Ako expected to repeat the survey to monitor the progress over a 12-month period.

Deepening the focus on teaching and learning at all levels

Rather than finding an ‘off the shelf’ solution, the Northcote Kāhui Ako considered the real value of operating as a Kāhui Ako was to understand and respond to the issues of their community. They were determined to know more about the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of their own situation so as to make a real difference. They decided to engage and reflect on the values and beliefs held by learners, parents, and teachers in the Kāhui Ako. ASTs undertook case studies of learners in the Northcote community from Years 1 to 13 involving interviews with a range of learners, and their parents and whānau. The focus was on understanding what constitutes success from different perspectives. The case studies were presented to and discussed at length with the WSTs and the Kāhui Ako leadership. Workshops with staff from all five schools were also undertaken to elicit teachers’ theories of what accounted for the variance in outcomes for learners in the community.

The case studies with learners and their families and the teacher survey identified the following:

- parents and whānau largely see success as being about a child’s enjoyment of school, their wellbeing, their connectedness to others, and their ability to be resilient and give things a go

- success as measured by national standards or NCEA was barely mentioned by families

- learners considered to be thriving have a history of multiple opportunities outside of school – being engaged in sporting, cultural, artistic, and community activities, for example

- learners considered to be struggling have often faced difficulty in the past that negatively impacts their sense of self-efficacy

- teachers at all year levels strongly believe that learner disposition (engagement with learning) is the biggest factor in learner success

- home factors were also identified as being important to disposition and academic progress

- teaching and learning practices were not identified as barriers by teachers, parents, and whānau in terms of learners achieving their potential.

Ōtūmoetai

Teaching collaboratively

The purpose of Kāhui Ako is essentially about improving the quality of teaching and learning through schools working collaboratively and sharing their knowledge and expertise. The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako put this intent into practice to help reduce variance and improve equity in student achievement within and across schools.4

Within this Kāhui Ako the creation of the internal advisory groups provided the platform for exchange of expertise and knowledge. By clustering ASTs and WSTs around an identified learning area, and providing them with a learning mentor to guide their inquiry, the Kāhui Ako aimed to bring about significant changes to the pedagogical and instructional practice of teachers. At the time this case study was undertaken, the Kāhui Ako leadership were building their capability by undertaking external professional learning and development.

Waimate

Multi-level approach

In the Waimate Kāhui Ako, collaborative practices for promoting learning and inquiry occurred at three levels. Members of the stewardship group undertook strategic collaborative inquiry focused on identifying what was happening for their learners. The knowledge gained from this inquiry helped the Kāhui Ako develop a shared understanding of their vision and aspirations. The collaborative inquiry processes used by the stewardship group made sure all participants had a voice in terms of how the challenges were identified to build a compelling agenda for change amongst all partners. The strategic planning session held in Term 3, 2017 with members of the stewardship group and the joint training for all trustees through NZSTA reflected the Kāhui Ako desire to shift from sharing and coordinating their work to achieving the best outcomes for learners in their district. Those involved believed the relationships were shifting from collegiality to working collaboratively to deliver their achievement challenges. This shift from developing a common agenda for change to sharing aspirations has been critical to the success of this collaboration.

For principals, the most common collaborative practice for learning and inquiry was the regular discussions with other principals in the Kāhui Ako. This included inquiring into student progress and strategies that could be used to improve progress of the students of concern within their teaching teams.

“It has lifted the expectations of quality teaching.”

In addition, given the significant number of first-time principals in this Kāhui Ako, the peer support received through the collaboration was described as invaluable. The principals have collectively come to appreciate and understand that being in a Kāhui Ako helps them achieve more for learners in the district.

For teachers in the Kāhui Ako, teaching as inquiry was a focus. The creation of the syndicate structure played an important role in supporting collaboration between teachers from different schools teaching at similar year levels. It provided a platform for inquiring into teaching and learning; sharing ideas and different ways of working; and discussing strategies that a particular teacher in the syndicate may have used, including reflections on why it worked or did not work.

“The opportunity to work with others rather than by oneself is important. It can be isolating in a rural school.”

“I have been a teacher for 15 years and this is the first time I am working with teachers from other schools in this district.”

More importantly, the relationships built with teachers from other schools paved the way for teachers to visit schools to observe and learn from one another. The trust and non-threatening climate in the syndicates brought teachers together in ways that were purposeful and meaningful and allowed teachers to share and transfer their expertise across the Kāhui Ako. For example, those with specialist learning support knowledge and skills provided professional support to less experienced teachers.

“In the beginning there were some challenges – just getting to know each other and building trust took some time. But getting to know and work with other teachers has been incredibly rewarding. I am enjoying it and find it very stimulating.”

“We have been on this journey together and we are much more comfortable with each other now. The opportunity to work with other teachers has stopped me from becoming insular and the realisation that the issues I face are the same as other teachers in the district and if we talked it through, we could come up with better, sharper solutions.”

While this is heartening, the real challenge lies in teachers leveraging their relationships and collective inquiry to change their teaching practices. Examining what the teachers are doing differently as a consequence of this deep inquiry into teaching and learning practices will be the litmus test for Kāhui Ako effectiveness.

Supporting ASTs and WSTs

The creation of cross-school syndicates provided WSTs with the opportunity to lead the learning of other teachers from all schools in the Kāhui Ako. The WSTs acknowledged that their initial reluctance and concern, which stemmed from lack of confidence, negative perceptions about workload, and newness of the role, had been put to rest. Opportunities presented through the role have developed their leadership capabilities significantly. Their decision to take a leap of faith was well rewarded. The WSTs meet at least twice a term to plan their syndicate meetings collaboratively and participate in PLD and provide regular progress reports to the stewardship group.

"I had great hesitation in applying for the role. I discussed it with my peers and family and chose to apply as I saw it as an opportunity to acquire some leadership skills. It also took me out of my comfort zone and has kept me challenged.”

“In the beginning there were some challenges – just getting to know each other and building trust took some time. But getting to know and work with other teachers has been incredibly rewarding. I am enjoying it and find it very stimulating.”

In the context of the Waimate Kāhui Ako, the use of the AST and WST roles as leading and spreading pedagogical change has increased capability and internal coherence within the Kāhui Ako. Those appointed to these roles act as a bridge between management and teachers.

Resourcing and infrastructure

Making the best use of roles and resources

A critical leadership function in the Kāhui Ako is to provide effective coordination and use of resources and the provision of supportive infrastructure. In these three cases, leaders worked hard to meet the complex challenge of developing cohesion across a group of self-managing organisations.

The time needed to build trust and to ensure collaboration at different levels and across the community was a major resource challenge for these Kāhui Ako. The allocation of AST and WST roles and responsibilities was also a major challenge. It was important to make the right decisions about these roles, for reasons of perception about the roles and for their effectiveness as a key part of the new structure. All three Kāhui Ako were deliberate and strategic in how they used these roles to fulfil the purpose of the community of learning.

Northcote

An inclusive approach to allocation of Kāhui Ako resources

The Northcote Kāhui Ako received an allocation for three ASTs and 16 WSTs. At the outset, however, the schools struggled to fill these roles. A lack of clarity around the work and responsibilities combined with the sector’s response to the Kāhui Ako venture resulted in little interest being generated in terms of finding people to achieve quota. Due to the overall confidence of secondary school teachers, there was a risk that all AST roles would go in their direction. Despite this fear, the stewardship group was deliberate in their allocation and distribution of roles across the schools. Duties and responsibilities have since evolved in a way that is likely to draw more interest and help recruitment in the future.

The distribution of roles clearly indicates this Kāhui Ako commitment to the spirit of collaboration and to reducing variability across member schools. For instance, when the stewardship group realised that Onepoto, a small primary school, did not generate any Kāhui Ako resources, they decided to allocate two WSTs from Northcote Intermediate to work exclusively with Onepoto teachers and parents. There was an explicit acknowledgement of the needs and priorities of the schools in the Kāhui Ako and the importance of linking the resources to meet them. The decision-making processes for allocation of resources appeared to be relatively smooth, reflecting the high relational trust that exists in this Kāhui Ako.

Ōtūmoetai

Allocation of across-school teacher (AST) and within-school teacher (WST) resources

Once achievement challenges were endorsed, and the Kāhui Ako received notification releasing the resources from the Ministry for the roles, the steering committee met to discuss the distribution of the resources across the Kāhui Ako. The Kāhui Ako was funded for seven ASTs and 35 WST positions. In line with the focus of the Kāhui Ako on intervening early, most of the resources were put into primary and intermediate schools. They also decided to allocate two WSTs to Brookfield School, despite its smaller roll. The decision-making process for the allocation was thoughtful and deliberate, and anchored in the operating model. These elements signal this Kāhui Ako commitment to use the operating model to guide decision making every step of the way.

Challenges overcome

The Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako was resourced to fund seven AST roles. Initially, the expected level of interest was lacking, which meant individuals were asked to apply. The biggest challenge for these appointments was lack of leadership experience, especially in terms of leading the learning of adults. To counter these challenges, the Ōtūmoetai Kāhui Ako created learning mentor roles. These arrangements have not only helped the Kāhui Ako to support ASTs to meet the expectations of their roles but also to grow their capability.

“The lack of clarity meant there was not sufficient interest in the roles. So we made a deliberate decision to identify people who could grow in their role as leaders. The learning mentors are helping the ASTs in this aspect.”

The WST roles also suffered from lack of interest, resulting in a mixed approach to these appointments across the Kāhui Ako. Since these were in-school appointments, member schools were given sufficient flexibility to appoint the roles to meet the needs of their school contexts. In some instances, recently registered teachers were appointed to the roles, which raised some questions in the teaching community. However, ERO’s study highlights that the WST roles have yet to take shape and form; at the time of writing they were “flying under the radar” with the expectation that they would take more leadership in the following year. This finding is consistent with the NZCER Teaching and Leadership practices survey.

Waimate

Doing it differently