Summary

This resource draws on recent Education Review Office (ERO) national evaluation reports to highlight how schools, both primary and secondary, have been evaluating teaching and learning and then using the findings to improve outcomes for students. ERO found that schools that significantly improved outcomes for students based their priorities for action on the findings from high-quality internal evaluation.

Whole article:

Internal evaluation as a catalyst for changeA resource for schools

The school is the primary agent for change, and high quality internal evaluation processes are fundamental in developing strategic thinking and the capacity for ongoing improvement[1].

This resource draws on recent Education Review Office (ERO) national evaluation reports to highlight how schools, both primary and secondary, have been evaluating teaching and learning and then using the findings to improve outcomes for students. Pursuing equity and excellence, some have made significant shifts in pedagogical, assessment and curriculum practice.

As is widely recognised, disparities in achievement are the single biggest challenge facing the New Zealand education system. Done well, internal evaluation can contribute to a reduction in these disparities by clarifying the nature and extent of the issues and providing a firm foundation for improvements.

The effectiveness of internal evaluation is contingent on the development of a professional culture in which staff feel safe to collaboratively investigate achievement and wellbeing data, identify disparities, and commit to bettering outcomes for those who are underachieving. In a strongly supportive culture, leaders and teachers are ambitious for all their students and responsible for playing their full part in improvement initiatives.

Internal evaluation as a catalyst for change

ERO found that schools that significantly improved outcomes for students based their priorities for action on the findings from high quality internal evaluation.

When determining priorities, schools need to identify students and groups of students for whom the status quo is not working. This requires good information about achievement and wellbeing, carefully scrutinised. Subsequent, effective action requires commitment and perseverance on the part of all stakeholders.

In some schools, improvements were triggered by the regular evaluation cycle, in others, by an emergent evaluation conducted in response to an unforeseen event, or an issue picked up by routine monitoring.

The leaders and teachers in these schools wanted to know how effectively:

- current programmes and practices were promoting the learning and wellbeing of all students

- programmes and practices designed to improve outcomes for all students had been implemented

- strategies to accelerate the progress of students in need of extra support were working.

Leaders and teachers worked collaboratively to:

- analyse information relating to achievement, progress and wellbeing

- notice successes and challenges

- determine what they should investigate further, and how

- source and use research and/or professional learning and development (PLD) to address issues that were identified

- determine and then implement manageable action plans

- involve all stakeholders in developments

- monitor the implementation and outcomes of agreed changes

- evaluate the extent to which agreed actions had accelerated the progress of target students.

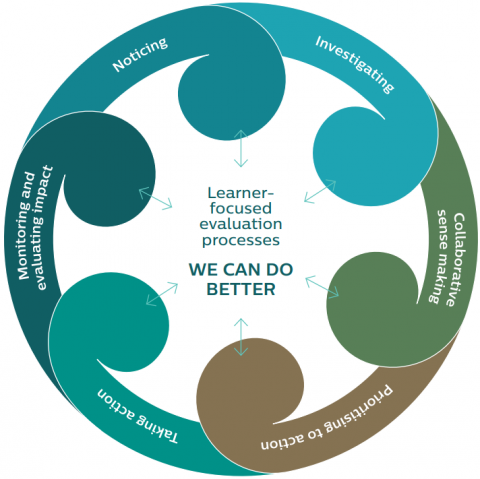

These six interconnected, learner-focused processes are integral to effective evaluation for improvement.

Examples of internal evaluation

School A

School A is a primary school in a low socioeconomic area. Analysis of achievement data showed that, for many children, progress slowed when they reached Level 2 of the curriculum.

As a next step, leaders and teachers consulted a range of research, which suggested that the slump could be due to:

- early reading difficulties

- variations in student’s knowledge of vocabulary as many had English as their second language

- lack of prior knowledge to engage in new learning

- the increase in peer influence.

In response, teachers enacted a number of measures that effectively addressed the loss of momentum. These included:

- implementing a spiral curriculum that built on the students’ prior knowledge

- a deliberate focus on developing students’ oral language

- involving parents and whānau as genuine partners in their children’s learning

- building a school culture in which peer pressure encouraged and rewarded success.

School B

When the leaders and teachers of School B compared reading data for the last few years, they noticed a decline in Year 1 reading achievement. This meant increasing numbers of students required additional support in Year 2. A review team, which included a member of the board of trustees, investigated possible reasons for the decline, asking parents for their perspectives.

After collecting and analysing further data, the team identified two areas for improvement:

- parents wanted to be more involved in their children’s learning

- teachers appeared to lack urgency for the children to progress.

In response, teachers began meeting more regularly with parents to discuss their child’s interests and progress, and any challenges. They raised their own achievement expectations and introduced practices designed to improve their students’ decoding and involve then more in assessment-for-learning activities.

As a result, Year 1 reading achievement improved and considerably fewer students needed additional support in Year 2.

School C

In secondary School C, teachers set their sights on lifting the NCEA level 2 achievement of a large group of students. Internal evaluation showed that some were achieving well during the year but failing to complete their work at the end of the year.

A leader identified that students taking two or more arts subjects had the burden of completing two major portfolios in Term 4. Teachers trialled different ways of spreading the workload and reducing the end-of-year pressure. These included allowing for earlier completion of design assignments and assessing work against standards that were more in line with the students’ interests and career aspirations. For example, some students completed their fashion design portfolio at the end of Term 3 and then worked on their photography portfolio during fashion design class time in Term 4.

Conducting effective internal evaluation

Gather a wide range of data

When seeking to establish priorities, schools generally start by analysing their achievement data. It is important, however, to consider a wider range of information. This includes information about wellbeing, teacher expectations, curriculum structure, coherence and scope, and contexts for teaching and learning.

Examples of areas that leaders and teachers explored as part of internal evaluation activities included:

- how well curriculum and assessment processes aligned with the school’s vision

- how well programmes reflected the school’s principles and local iwi plan

- the extent to which curriculum made use of local contexts, reflected students’ interests and cultures, and focused on wellbeing and values

- the extent to which students had opportunities to explore and develop the key competencies

- areas that long-term teaching programmes prioritised or ignored

- the learning opportunities that students experienced as they moved through school

- the opportunities students had to contribute to the contexts they would explore

- how well the school curriculum reflected The New Zealand Curriculum

- how literacy and numeracy learning were integrated into other learning areas

- the extent to which teachers expected all students to progress and achieve

- how streaming in secondary schools or cross-grouping in primary school classes influenced wellbeing and access to knowledge and skills required for future success

- how effectively the school worked with early learning services and contributing schools to gain insight into the children’s previous learning experiences

- how well course content and pedagogy responded to the interests and aspirations of students

- the difference mentoring of Year 11 to 13 students was making in terms of NCEA achievement.

Analyse the data: what stories can it tell?

Leaders and teachers collaboratively analysed data relating to achievement, progress and wellbeing, looking at their own performance as well as that of their students. They recognised that, by working collaboratively, they:

- gained a more complete picture of what was and was not working

- built collective commitment to improvement

- built evaluative capacity.

Collaborative work of this kind required a foundation of relational trust. Further, high quality information and a focus on professional capabilities influenced how well any challenges and successes were fully understood and can be responded to.

Building collective capacity to do evaluation

Collaborative sense making

- Teachers interrogated their own data and contributed their insights to syndicate, department or whole-school analysis.

- Teachers shared their own inquiries (individual or group) with others and collaboratively analysed the results.

- Leaders and teachers analysed the data together, looking to identify patterns and trends.

Relational trust

- Leaders built a culture where it was okay to take risks.

- Teachers were fully supported to make necessary improvements.

- New leadership opportunities used or drew on teachers’ strengths.

- All stakeholders’ views were valued and responded to.

- Improvements for students were central to every decision.

High quality information

- Leaders and teachers made changes to their assessment practices to ensure that the data gathered provided specific information about what was working and what was not.

- Leaders and teachers widened the focus of their data gathering.

- Leaders checked how curriculum, learning and assessment processes and practices aligned with the school’s vision, values and principles.

Focus on professional capabilities

- Information about teachers’ confidence with current or agreed teaching practices was collected and analysed.

- Class, syndicate and departmental systems were evaluated and improved to ensure they contributed to schoolwide initiatives.

- Teachers’ own inquiries (individual or group) were linked to school goals and targets so that everyone was able to focus on the agreed improvements.

Responding to findings

Schools that made the greatest improvements chose to focus on just one or two areas. The leaders in these schools were acutely aware that goals needed to be both challenging and manageable. Challenging goals named and addressed groups of students for whom current practices were not delivering. Manageability was largely a matter of having or developing the necessary capacity and limiting competing demands on time and energy.

Effective leaders:

- understood that taking action to achieve equity was a moral imperative

- led discussion about disparities in achievement, which helped teachers and trustees appreciate the urgency of taking measures to identify and respond to gaps

- promoted shared understanding and commitment by working collaboratively with teachers to develop goals

- shared relevant information with trustees to help them understand the challenges and make considered resourcing decisions

- implemented short-term plans to accelerate the progress of some students and longer-term plans to permanently reduce disparities

- shared and discussed goals in partnership with target students and their parents and whānau

- sometimes shared goals with the whole school

- developed improvement plans that were complete with timelines, responsibilities and actions.

Engage in professional learning & development for improvement

Well-considered and managed PLD was a feature of the schools that made significant improvements. The PLD provided multiple opportunities for in-depth professional learning and included monitoring of teacher practice for evidence of the desired changes.

Effective PLD: five key factors

- Leaders sought out PLD that focused on the specific skills needed.

- Planning began with an assessment of teachers’ and leaders’ confidence in relation to the curriculum knowledge and pedagogical skills that the improvements would require.

- Leaders worked closely with external PLD facilitators and participated in PLD with teachers.

- PLD developed the confidence of leaders by showing them how to engage with research, lead workshops, model new practices, coach teachers, undertake structured observations and monitor assessment data.

- PLD content and delivery were flexible, catering for each teacher’s strengths and needs.

Two schools make PLD decisions

Teachers in one secondary school were focusing on developing culturally responsive teaching practice. When the leaders looked at the achievement results for students in a particular subject department they found unacceptable levels of progress. As a consequence they excused teachers in that department from most school-wide PLD and set in place a separate programme designed specifically to improve teaching in that subject.

In one primary school, literacy leaders were looking to improve writing achievement. They attended several external one-day workshops and talked with providers before selecting a provider that offered teaching strategies they had not used before. They rejected PLD that repositioned strategies they were currently using, which were neither helping their reluctant writers nor increasing teachers’ confidence in their ability to teach writing.

Monitor and evaluate changes

Leaders worked closely with teachers as they introduced targeted interventions and school-wide changes in teaching practice. They knew that without support and monitoring they couldn’t be certain of implementation fidelity or of the impact of the changes on student outcomes.

Implementation and monitoring practices included:

- trialling new strategies with a small number of teachers who then supported others to introduce the same strategies

- using ongoing analysis of achievement data, surveys and interviews to design PLD workshops that individual teachers then opted into to improve their confidence

- observing teaching in other classrooms and working across class levels to better understand learning progressions and expectations

- collaboratively revisiting achievement expectations and long-term plans with the aim of ensuring that programmes built on prior learning

- ensuring trustees received and discussed information about student progress and wellbeing so that they could assess the effectiveness of resourcing decisions and make necessary adjustments

- developing reflective practice through coaching and mentoring, thereby shifting some of the responsibility for identifying successes and issues from leaders to teachers.

A coaching model adopted in one primary school

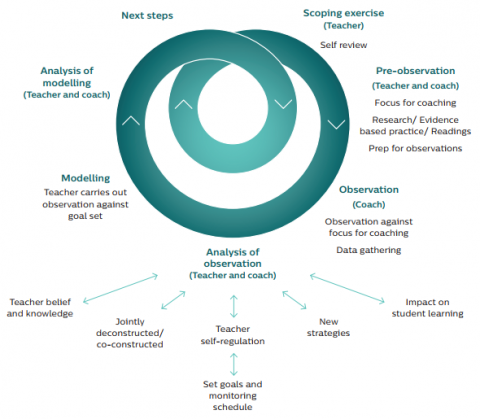

Leaders and teachers at one school developed and adopted the coaching model shown here to help them link their own inquiries, provide them with multiple opportunities to explore their practices and beliefs, and assess the impact of their practices.

The diagram highlights the joint roles involved in making improvements to teaching and learning.

Leaders were also working on linking individual teachers’ inquiries to school-wide inquiries.

Leadership involvement

Principals in schools that showed the greatest improvement were compelled by a sense of urgency to improve outcomes for their current students while also having an eye on longer-term goals. Several spoke to ERO about the ‘moral courage’ required to lead a school to improve students’ outcomes and wellbeing and reduce disparities. These principals talked about ‘soft’ skills or competencies and human values – they were committed to developing their students’ personal qualities. They understood that high expectations and quality internal evaluation and improvement processes were fundamental to supporting students to achieve their potential.

School leaders:

- influenced outcomes mainly through their leadership of pedagogy and their impact on the school’s culture and values

- ensured that goals for students were well-communicated and understood, had buy-in from teachers, parents/whānau, trustees and students, and created optimism amongst teachers that they could improve learning

- distributed leadership to teachers who had pedagogical expertise that aligned with the school’s improvement priorities

- were committed to a broad definition of ‘successful outcomes for students’, which reflected the principles, vision, values and key competencies of The New Zealand Curriculum

- emphasised the ethics of teaching and challenged assumptions and expectations relating to the learning capacity of particular students and groups of students

- encouraged teachers’ creativity and challenged them to unpack the assumptions that sat behind their everyday practice

- directly involved themselves in planning and evaluating curriculum, teaching and learning

- ensured that resources were made available as required for PLD workshops, coaching, observations, interviews, and developing teaching resources.

Rethinking assessment practices

In many of the schools that made significant improvements, internal evaluation led to changes in assessment processes and practices. Leaders and teachers could see that they did not always have access to or use high-quality assessment information when determining priorities for improvement. By adjusting their assessment tools and processes they were able to ensure that the information they collected was useful not only for teaching and learning but also for internal evaluation.

This involved clarifying the purpose of each assessment and then selecting tools that would provide achievement, progress and wellbeing information that could be used to determine next teaching steps and priorities for development. Leaders and teachers put the students at the centre of evaluative processes, seeking to minimise disruptions and considering the following questions:

Do our assessments benefit the student?

- What is the purpose of each of our current assessments?

- Do students understand and see the benefits of participating in these assessments?

- Are our current assessment tools contributing to learning and wellbeing or are they reducing teaching time and increasing student anxiety?

- Are the assessments we use fit for purpose or just continuation of a long-standing tradition?

Is assessment information fully used?

- Are we gathering information that we are not using fully?

- Are we judiciously using the results of a single assessment activity for multiple purposes (for example, student goals, teacher planning, reporting to parents, reporting to the board, internal evaluation) or using a different assessment for each purpose?

- Do we modify our teaching plans in response to what we learn from assessments?

- Is the achievement information we have adequate for internal evaluation purposes?

Are assessment processes motivating or demotivating for students?

- Do students know what is being assessed and what they can learn from the results?

- Do we value and respond to peer- and self-assessment information or is only information collected by teachers used as part of reporting and school-evaluation?

- Do we value and make use of students’ perspectives as expressed in interviews and surveys?

- Can students see that teaching is responsive to whatever assessments reveal?

Are parents included as part of a genuine learning partnership?

- Do parents contribute what they know about their child’s learning and wellbeing or do they just receive information?

- Can parents view assessments and provide their perspective on their child’s results?

- Are parents able to contribute insights and perspectives on their child’s goals and learning?

- Do collaboratively developed goals outline teacher responsibilities as well as those of the students and parents?

Are our assessments useful for students needing additional support?

- Will we get useful information if these students do the same assessments as their peers?

- Do we need additional assessments, or assessments at a slightly lower level, to clearly identify strengths and needs?

- What formal and informal assessments will provide ongoing information for the board about target students and special needs students?

Is the information we gather used to Identify teaching strengths and needs?

- Is the information used for planning PLD and for monitoring how new practices are working for teachers and students?

- Are we able to use the information to identify gaps in the curriculum?

- Is the information we gather used only to identify students’ progress and wellbeing without considering the quality of the teaching?

- Is the information used to group students for the purpose of learning specific skills or just to group students by curriculum level or reading age?

How are our assessment processes impacting on senior secondary students?

- Are we monitoring each student to ensure that they are achieving meaningful credits, have up-to-date information about their progress, understand what their next steps are, and know how they will be supported to achieve success?

- Are we aware of the competing assessment demands made of students in their different classes, and do we exercise flexibility where appropriate?

- Are students able to take the assessments they need for their intended careers, or do streaming, banding or timetabling constrain their future options?

- Do assessments drive teaching or do teachers use assessments in conjunction with rich learning experiences?

- Does information about student wellbeing from surveys, interviews, careers and guidance staff, and health professionals feed into school-wide improvement?

The following examples describe changes that four schools made to their assessment processes following internal evaluations.

High School A

In High School A, an analysis of assessment and reporting information showed that some teachers were rather too accepting of slow progress and low achievement. To raise expectation levels, the leaders decided it was important to clarify what a year’s progress looked like. This would also give students a clearer picture of their own progress and achievement. Teachers from each learning area took responsibility for describing a year’s progress at each level. They designed a framework of indicators that the students were then able to use to review their own progress, and, in discussion with their teachers, update their learning goals.

High School B

Teachers in High School B recognised that their curriculum needed to be more student-centred, more responsive to students’ interests and goals. One outcome was the introduction of a course that combined technology and science and then extended into other subject areas. The teacher of this course interviewed the students about their interests and passions and then put them in groups to tackle projects that matched their inclinations. Together the students and teacher looked at the available NCEA standards and selected those that were most relevant to the projects the students had chosen. Those who spoke to ERO could explain how they had chosen specific standards from science, technology, history, legal studies and geography as part of their technology and science course. The students also developed self-management, entrepreneurial and collaborative skills – competencies that local businesses had identified as desirable.

Primary School C

Leaders at Primary School C had been working on improving their teaching, but they could see from the data that many Year 1 and 2 children were still not meeting expectations for reading. As a result, they decided to change how they engaged with parents. This change meant that teachers would share with parents the assessments used, together with examples of the child’s work. Teachers and parents would then discuss what the assessments revealed and formulate next steps as specific learning goals. The parents would discuss how they could support their child’s learning at home and the teacher would explain how they planned to support the child’s learning at school. Parents were given resources to support the home learning. Considerable improvements in students’ achievement, in reading and other curriculum areas were evident from the time teachers started working more closely with parents. As a bonus, younger siblings started school with an orientation towards literacy, which meant that their reading also progressed more rapidly once they reached school.

Primary School D

Teachers at Primary School D recognised that they were not consistently interrogating achievement data to learn how their teaching was impacting on student outcomes, so they introduced this set of focusing questions:

- What do we know from the data?

- How do we know this?

- What do we still need to know?

- What do we need to do?

These questions helped them address a dip in mathematics achievement by:

- identifying the issue and the associated learning needs of children and teachers

- devising and applying short-term strategies to support children below the expected level

- introducing long-term teaching strategies designed to reduce the risk of the dip recurring.

Curriculum evaluation, development and implementation

The schools that made the greatest gains in achievement and wellbeing had carefully evaluated their curriculum in terms of the following four factors: cohesion, inclusiveness, cultural responsiveness and alignment to The New Zealand Curriculum.

When evaluating cohesion they focused on:

- reviewing long-term plans and teaching programmes to see how learning was scaffolded from level to level

- reviewing what the students were learning at each year level (content, skills and dispositions): was this equipping them for the future?

- back-mapping senior course content to the related junior course content to check that students were developing the knowledge and skills they would need for success in senior classes

- how well literacy and numeracy learning were integrated across teaching programmes

- (secondary schools) how competing priorities could be reduced, and alignment increased across subjects

- how well the curriculum aligned with the school’s professed vision and values.

When evaluating inclusion they focused on:

- how successfully the curriculum incorporated the interests and met the needs of its students

- the extent to which students with additional learning needs were included in all aspects of school life

- whether students were respected partners in their learning and able to recognise their own learning and progress

- whether grouping practices motivated students by matching interests and needs rather than just learning levels

- whether course restrictions were preventing students from gaining qualifications they needed for their careers

- whether the views of parents and students were sought and considered when planning curriculum

- the extent to which local experts, resources, places, and parents were made use of in curriculum planning and delivery.

When evaluating cultural responsiveness they focused on:

- the extent to which teachers developed culturally responsive teaching practices through careful listening, genuine conversations, and strong relationships with students and whānau

- how successfully the curriculum was supporting the development of students’ identities.

When evaluating alignment to

The New Zealand Curriculum they focused on:

- identifying skill and knowledge gaps (such as literacy and numeracy) that might prevent engagement with the whole curriculum

- how well programmes used local contexts matched the students’ interests, strengths and learning needs

- the extent to which the school was fostering values and key competencies through engagement with a stimulating curriculum in a high-trust environment.

The following examples describe changes that three schools made following internal evaluations of their curriculum.

School X

Aware that teenagers often change their minds about career or further education or training, leaders and teachers at Secondary School X restructured their senior courses to allow students to keep their options open for longer. Along with mathematics and English, science was also made compulsory in Year 11 because it is a prerequisite for further education in so many areas. Based around vocational contexts, students were able to select the science course that best aligned with their interests and aspirations. Teachers addressed the perception that physics is difficult by revising the course content and changing the way it was taught. As a result of this student-centred approach there was a lift in Year 11 NCEA science achievement, and multiple Year 12 physics classes had to be timetabled instead of just one.

Secondary School Y

In Secondary School Y, the head of English reviewed the Year 10 reports and then discussed with the students their interests, likes and dislikes. It became evident that some of the boys were getting positive comments for physical education and health but not for their other subjects. As a result, the department set up a sports-themed English course specifically to engage such students. Other themed Year 10 English courses followed: Pacific voices, digital English, English Classics, and humanities English (social justice and social change). The humanities course was particularly popular and linked to the school’s vision of having its graduates ‘recognised as thinkers, contributors and participants in the local, national and global community.’ Classes were not streamed, as teachers differentiated their approach for the different abilities. Following these changes, the school saw an increase of about 20 percent in their overall achievement in Level 2 NCEA.

Primary School Z

The leaders and teachers of Primary School Z recognised that they needed to do more to promote success for Māori, and that deeper learning demanded a more responsive curriculum – one that valued the students’ heritages and was cognisant of their interests. As a result, the school introduced two major changes.

The first was to give all students opportunities to learn about their significant local history and share and build on their experiences. Leaders, teachers and trustees worked with a cluster of schools to learn from each other how they taught te reo me ona tikanga. When planning local history units, the school’s Māori leaders met with a leader of the local rūnanga to learn more, and then discussed their ideas with whānau.

The second change involved teachers working with others in the cluster to develop teaching practices that supported deeper learning. This led to the realisation that learning would be enhanced if teachers worked in partnership with the students. One outcome was that teachers invited groups of Year 4 to 6 students to work with them when planning integrated topic studies. The students made many suggestions concerning things that were important to them, both in the school and in the community.

To learn more, read these ERO national reports

This resource highlights successful processes and actions from a range of schools that ERO has visited in recent years. See the following reports for further information about how schools were doing and using internal evaluation for improvement:

Keeping children engaged and achieving in writing (2019)

Keeping children engaged and achieving through rich curriculum inquiries (2018)

Keeping children engaged and achieving in mathematics (2018)

Keeping children engaged and achieving in reading (2018)

Building genuine learning partnerships with parents (2018)

Leading innovative learning in New Zealand Schools (2018)

What drives learning in the senior secondary school? (2018)

A decade of assessment in primary schools – practice and trends (2018)

Case Study: Improving Māori student achievement and wellbeing (2018)

Teaching approaches and strategies that work (2017)

School Leadership that works (2016)

Wellbeing for Success: A resource for schools (2016)

Effective School Evaluation (2016)

Effective Evaluation for Improvement (2015)

Wellbeing for children’s success at primary school (2015)

Wellbeing for young people’s success at secondary school (2015)

Raising student achievement through targeted actions (2015)

Internal Evaluation: Good Practice (2015)

[1] MacBeath, J. (2009). Self Evaluation for School Improvement. In A. Hargreaves, D. Hopkins, A. Lieberman, & D.M. Fullan (Eds.), Second International Handbook of Educational Change, 23, 901–912. New York: Springer.